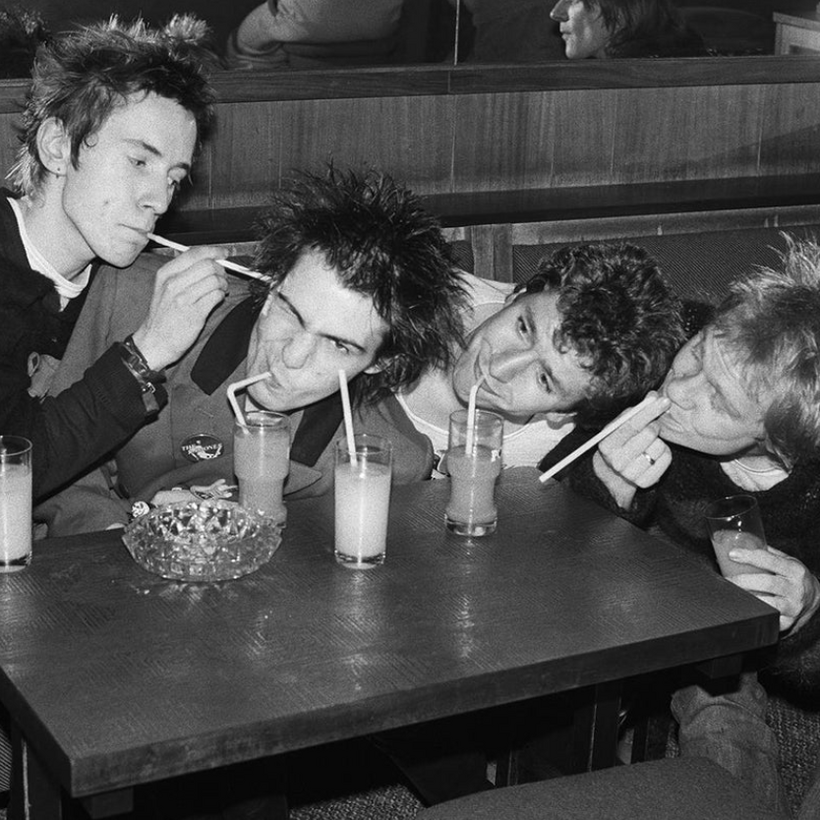

“Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated?” These were the immortal words of Johnny Rotten at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco, January 14, 1978. That was the night he walked away from the Sex Pistols in disgust, endeavored to file a lengthy lawsuit against the Pistols’ manager, Malcolm McLaren, became John Lydon again and began a decades-long alienation from his bandmates — the guitarist Steve Jones, bassist Glen Matlock and drummer Paul Cook — that, broken briefly by reunion tours in the 1990s and 2000s, continues to this day.

“John got lead singer disease the moment his boat race got in the papers,” says Matlock, 68, who left the band in February 1977. That came three months after Lydon and Jones went on Bill Grundy’s Today show, swore on live television and went from unknown rockers to tabloid bêtes noires overnight. “I was getting all this shit from John and Malcolm. I heard they tried out Sid [Vicious] on bass, and I only hung in there because I was getting my wages. So I left. Then Malcolm sent a telegram to the NME, saying he sacked me because I liked the Beatles.”