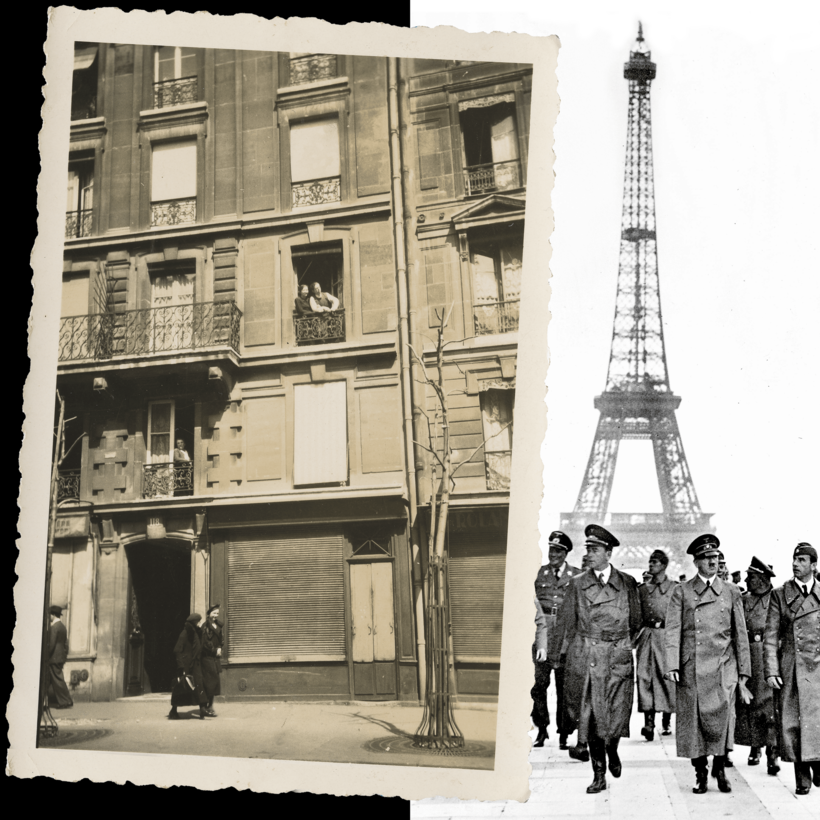

The photograph on the cover of a new book just published in France shows a contented-looking couple, Israël and Hélène Malowanczyk, standing close together on the balcony of their apartment on Avenue Parmentier, in Paris’s 11th Arrondissement. Lit by the sun, they gaze down upon the city below.

Israël was Polish; Hélène, French. Both were Jewish. Tango aficionados, they’d met at a dance competition in the city’s Bois de Vincennes. By 1935, when the photo was taken, they’d been married for five years and had two daughters. (Like the vast majority of Parisians at the time, the couple rented their home.)