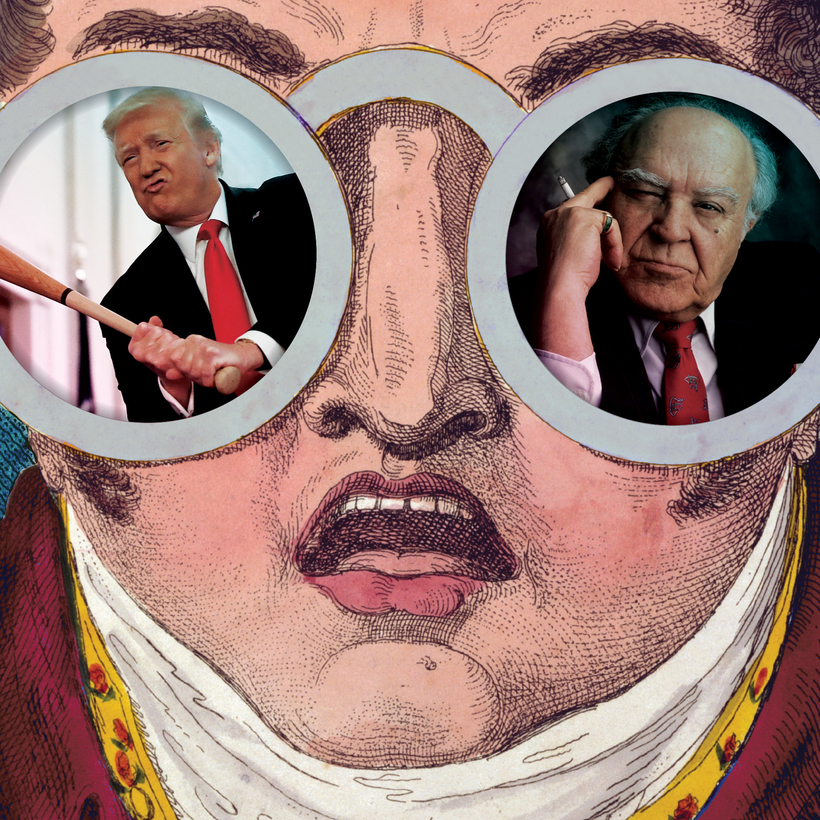

Normal American politicians can be expected to say they admire Lincoln, or F.D.R., or Reagan. Not Donald Trump. “Meade ruled with an iron fist,” he said admiringly of Amadeo Henry Esposito, who ran the Brooklyn Democratic Party for 15 years, from 1969 to 1984.

Trump recalled Esposito having a baseball bat under his desk and, in his dotage, swinging a cane at uncooperative elements. Esposito, an old-time machine boss with a cigar perpetually clenched between his teeth, doling out threats, promises, and patronage, was the sort of leader Trump hoped to encounter in Washington and to become himself. “I figured,” Trump told Maggie Haberman of The New York Times, “that the Mitch McConnells would be like him in terms of strength.” Instead, he found the staid G.O.P.