“Fascism also did good things,” goes a common Italian catchphrase.

While often used sarcastically to mock true believers, the idiom reflects Italy’s enduring ambiguity toward Fascism, even 80 years after its fall.

Only a fringe minority openly venerates Mussolini’s legacy, but the belief that Fascism wasn’t entirely evil—that beneath the violence and racism lay a desire to modernize Italy and, yes, make the trains run on time—still lingers insidiously in the national psyche.

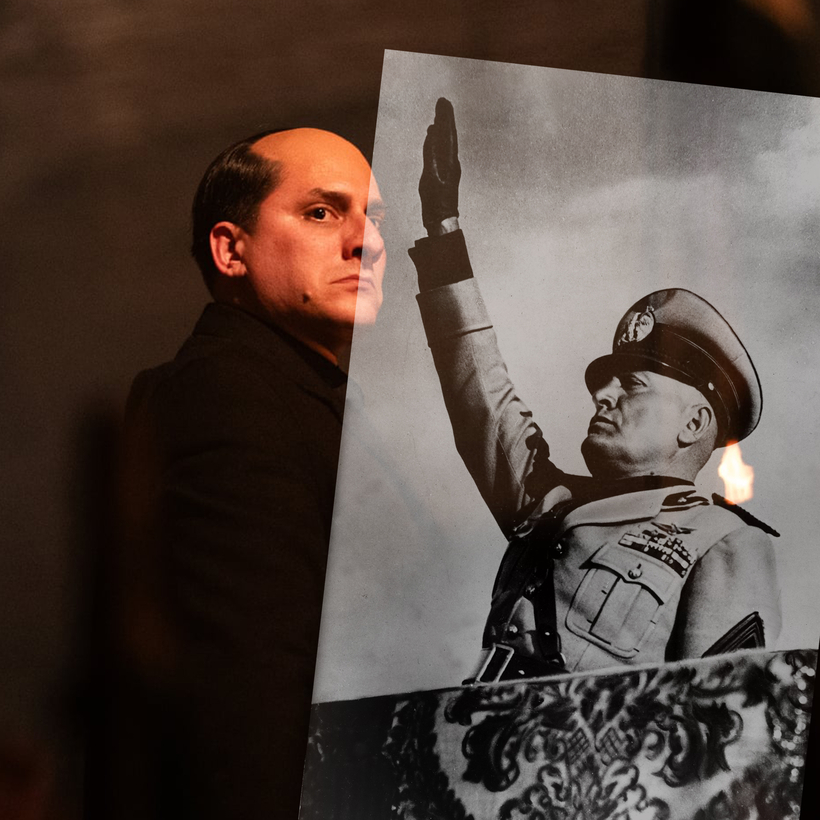

This tension has been re-ignited by M: Son of the Century, an Italian TV series, directed by Joe Wright, which premiered in Italy on January 10 and is set to debut in the U.K. on Tuesday. (A U.S. release date has not yet been announced.)

M—based on Antonio Scurati’s tetralogy of fictionalized biographies on Mussolini—has sparked intense debate across the country. It struck a particularly powerful chord under Giorgia Meloni’s post-Fascist government and amid the global surge of far-right populism.

The major publications praised it. Il Corriere della Sera, Italy’s most widely read newspaper, called it “a series that traces a before-and-after in a national television drama.” Meanwhile, the niche northern paper Il NordEst Quotidiano dismissed it as “an insidious caricature.”

In the streets, thousands of posters saying, “Long live M,” appeared across several cities, signed by the neo-Fascist group CasaPound. Meloni, for her part, waved the show off, claiming she hadn’t watched it because she had “different priorities.”

Her silence is unsurprising, given that her party, Brothers of Italy, traces its roots to Italy’s postwar neo-Fascist movement. Ignazio La Russa, president of the Italian Senate, proudly collects Mussolini memorabilia. And every year, hundreds of black-clad extremists gather to commemorate far-right militants killed in 1978 by an armed leftist group, while party leadership conveniently looks the other way.

M clearly addresses these realities: “Look around you … we’re still here,” Mussolini says in his opening monologue. The philosopher Umberto Eco’s theory that Fascism wasn’t a regime, but an eternal force that would re-emerge under “the most innocent of disguises,” is central to Wright’s portrayal.

Certainly, the parallels with Donald Trump are striking. Mussolini is shown as a vulgar, opportunistic con man who manipulates institutions with constant lies and contradictions. What’s worse, he’s proud of it.

“I am consistent; I betrayed everybody. I will betray myself too,” Mussolini says in one scene before flashing his middle finger at Socialist Party M.P.’s—the same party he led from 1912 to 1914. Then, before taking his oath as prime minister, in 1922, he makes a chilling statement—four all-too-familiar words: “Make Italy great again.”

The lead actor, Luca Marinelli, says embodying Mussolini was “devastating from a human standpoint,” while underscoring the show’s resonance in contemporary society.

There is indeed a powerful darkness in Marinelli’s performance. And M is visually stunning, exceptionally well written (although some of its wit may inevitably be lost in translation), and entertaining.

Wright made some bold creative choices—including having Mussolini break the fourth wall to address the audience directly and enlisting Tom Rowlands of the rock duo the Chemical Brothers to create a high-octane soundtrack.

But from a historical standpoint, the series is about as insightful as a Wikipedia page. Mussolini is reduced to a caricature—a one-dimensional comic-book villain—unlike the nuanced antiheroes popular today.

In real life, Mussolini was bullied and later became a bully (by age 10, he had stabbed a classmate). In M, however, there are no mitigating circumstances—Mussolini is portrayed as irredeemably bad, driven by brutish instincts in his rise from political journalist to dictator. When he’s not busy directing his thugs to beat, torture, and kill, he’s exercising his rapist lust.

Before taking his oath as prime minister, Mussolini makes a chilling statement—four all-too-familiar words: “Make Italy great again.”

While Mussolini’s personality dominates the screen, the broader historical context fades into the background. Many historians have criticized the portrayal, arguing that it perpetuates Italy’s tendency to downplay Mussolini’s actions rather than examine them critically.

The historian Roberto Chiarini applauds the anti-Fascist message of M: Son of the Century but says it is oversimplified: “It confirms Italians’ historical alibi, who tried to place all the blame for Fascism on Mussolini to absolve their own conscience.”

After World War II, Italy never engaged in a collective reckoning like Germany’s Vergangenheitsbewältigung, which aimed to process past horrors through public debate. Instead, postwar anti-Fascism became a cornerstone of Italian democracy—a myth that cast the nation as having resisted Mussolini despite widespread support for him. Italy rejected Fascism without dismantling its structures or confronting complicity, allowing it to persist in the national psyche.

“The shared source of the republic’s legitimacy was anti-fascism,” Chiarini says. “But anti-fascism needs fascism to exist. In their eagerness to move on from the past, Mussolini’s staunchest opponents inadvertently made fascism a pillar of their new democratic identity.”

So, Fascism in Italy lives on. Films, books, and debates will crop up time and time again—and the ghosts of the past will return, demanding a new reckoning.

M: Son of the Century will be available on Sky Atlantic and Now TV in the U.K. starting February 4, and in the U.S. later this year

Mattia Ferraresi is the managing editor at the Italian newspaper Domani