One would think that the war on drugs would include at least a battle or two against crypto. After all, crypto-currency is how drug lords—and narco-state presidents—often fund their criminal enterprises.

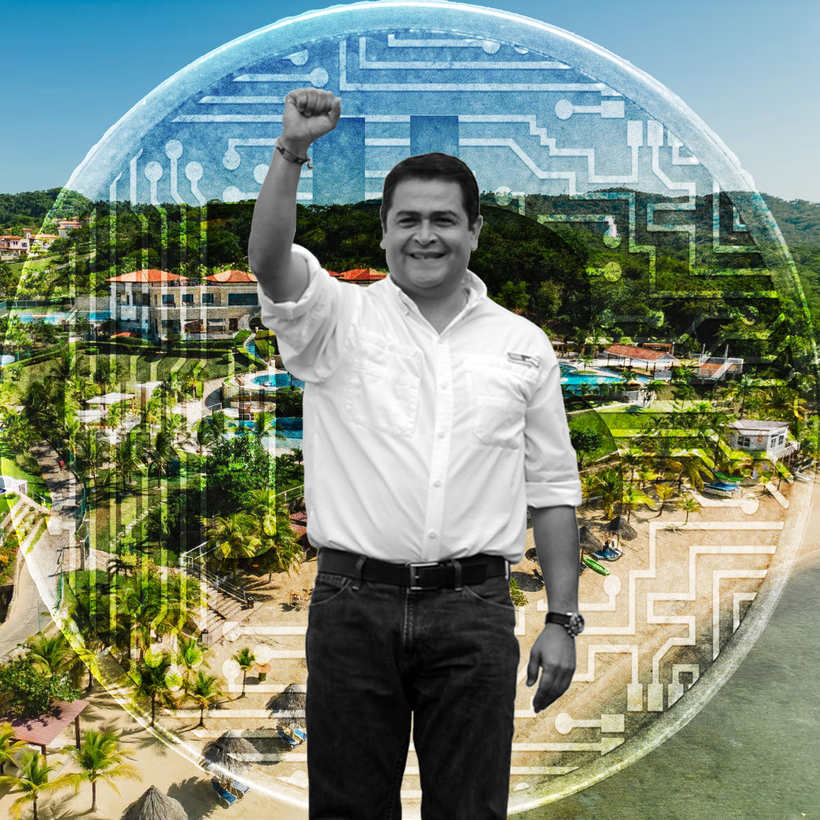

But as the U.S. military was blowing up alleged drug smugglers in the Caribbean, Juan Orlando Hernández, the former Honduran president who had been serving 45 years in jail for trafficking more than 400 tons of cocaine into the United States, was being pardoned by the president. And it was the crypto bros, it seems, that won him his pardon.