Hidden Portraits: Six Women Who Shaped Picasso’s Life by Sue Roe

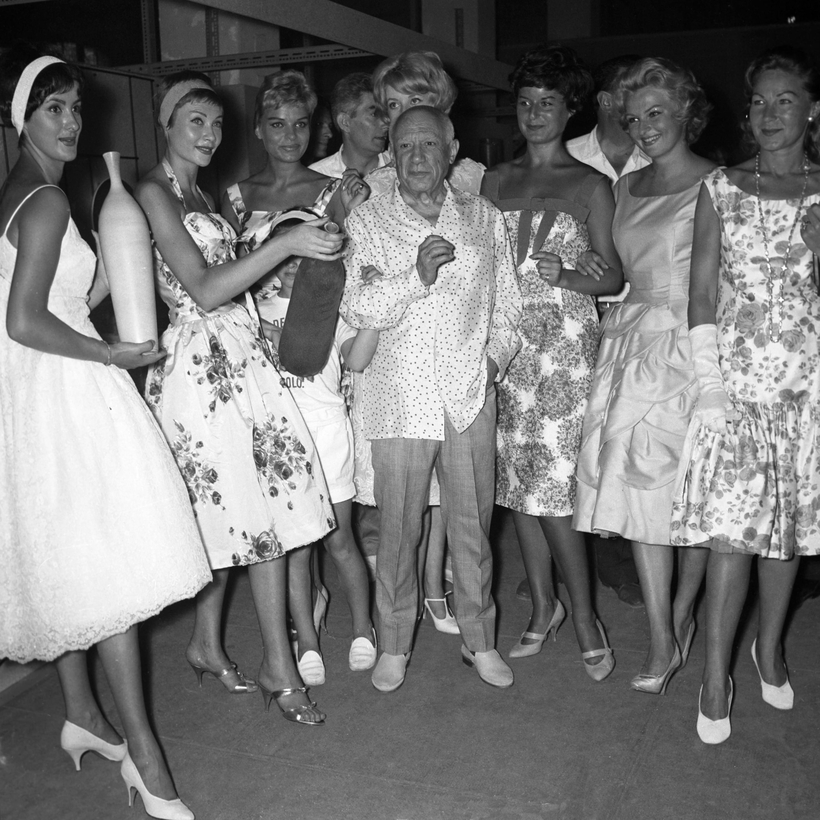

“Ma femme, c’est merveilleux” were supposedly the parting words of Pablo Picasso, moments before he died at 91 in his Provence farmhouse in 1973. They were intended for his then wife, Jacqueline Roque, the final Picasso femme—but it doesn’t take a titanic feat of research on the love-crazed Andalusian to wonder just how many other merveilleux women he bestowed the same gooey honorific upon.

Picasso’s philandering began at the tender age of 14, when he patronized his first brothel. The next eight decades saw an almost endless parade of women who should’ve known better but couldn’t help themselves. Sue Roe’s Hidden Portraits covers six of them (though there were many, many more).