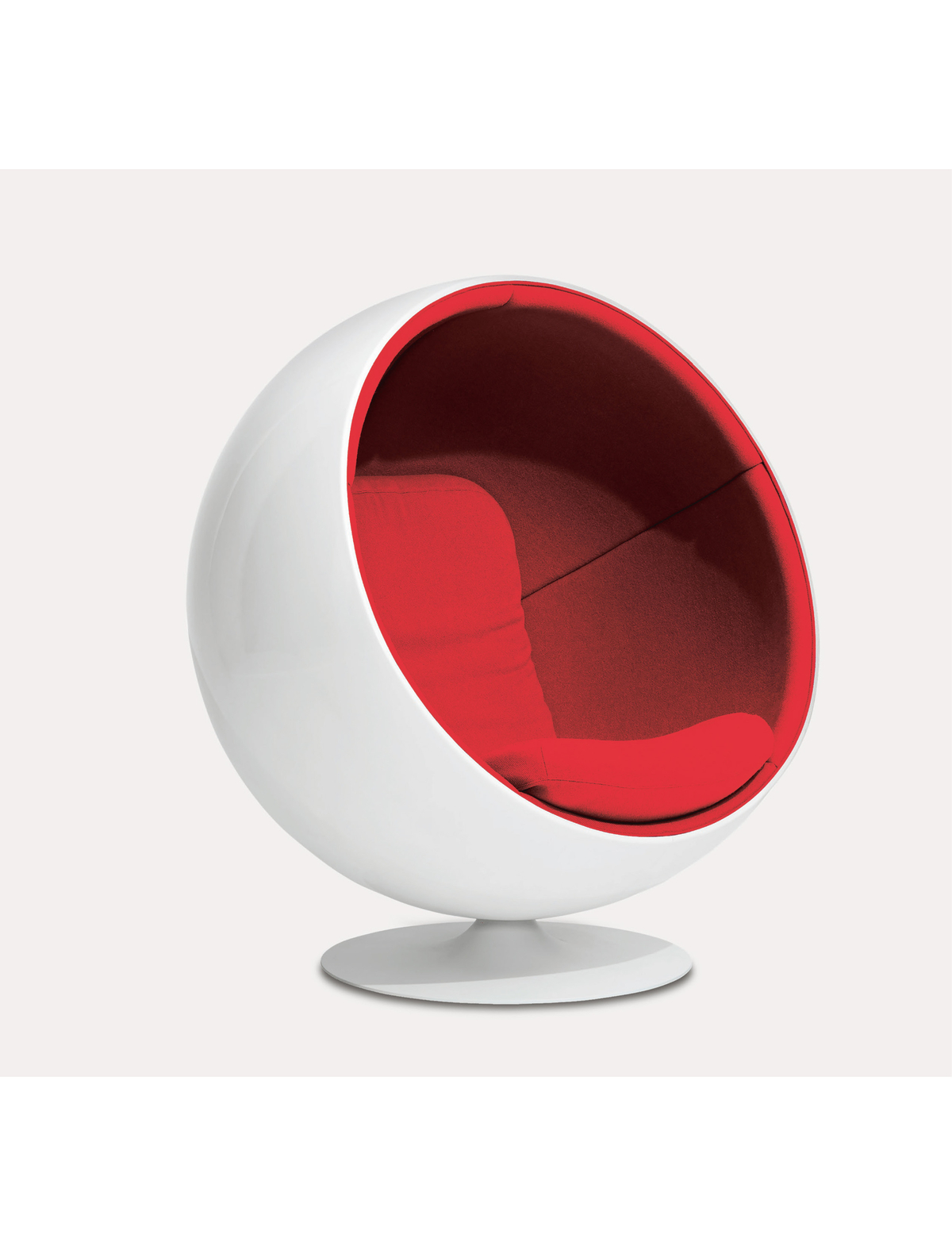

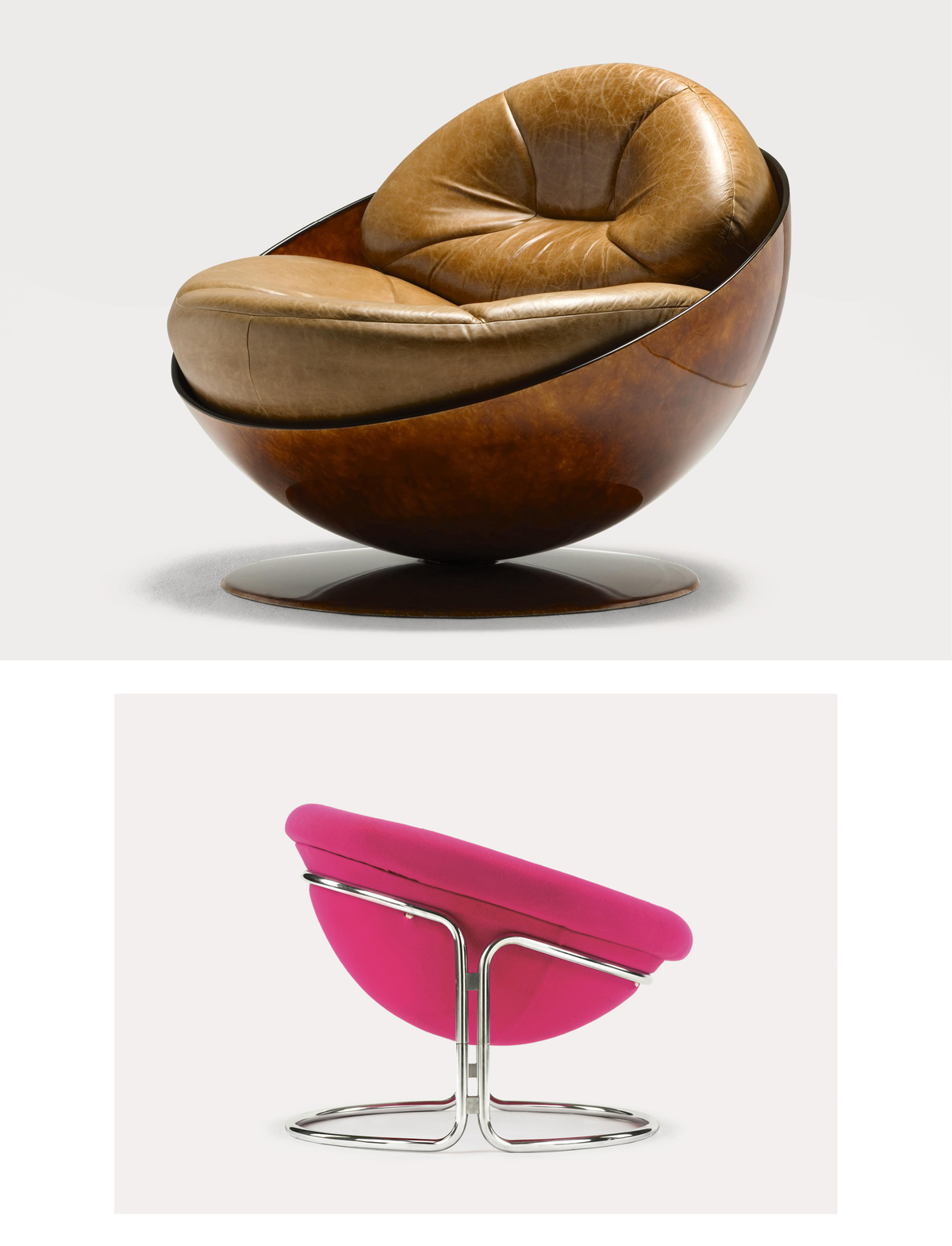

In the mid–20th century, designers began their escape from the straight-backed furniture of their predecessors. In came rounded forms with ergonomic character—soft, sleek, and easy on the body.

Before the war, during the economic austerity of hyperinflation, Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer—two leading lights at the Bauhaus, in Germany—argued for “democratic design.” They paired industrial materials with mass-production techniques.