It was December 2010, and I was in Brooklyn. Shane Smith waved his hand, motioning me to his table in the Hotel Delmano, a low-lit hipster saloon in Williamsburg. Three shots of tequila were arranged in front of an empty seat. “Say hello to your three little friends,” Shane announced. “Drink those, and we’ll talk.”

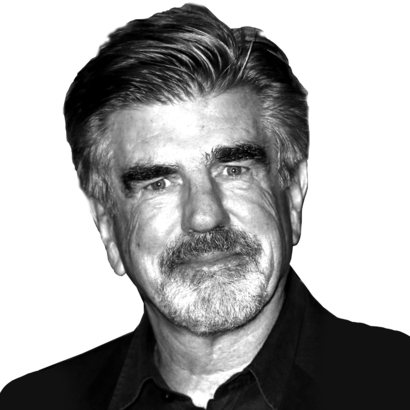

Shane, the 41-year-old cofounder and C.E.O. of Vice, wanted to rekindle our relationship. A bear-sized man with extensive tattoos across his torso and up and down his legs, a salt-and-pepper beard, and stringy long dark hair swept back over his red Irish face, Shane was complicated … a punk, a showman, a shaman, a sweetheart, a blowhard, an intellectual of weird shit, and a family man. He was also a man of large appetites, which sometimes got the best of him.