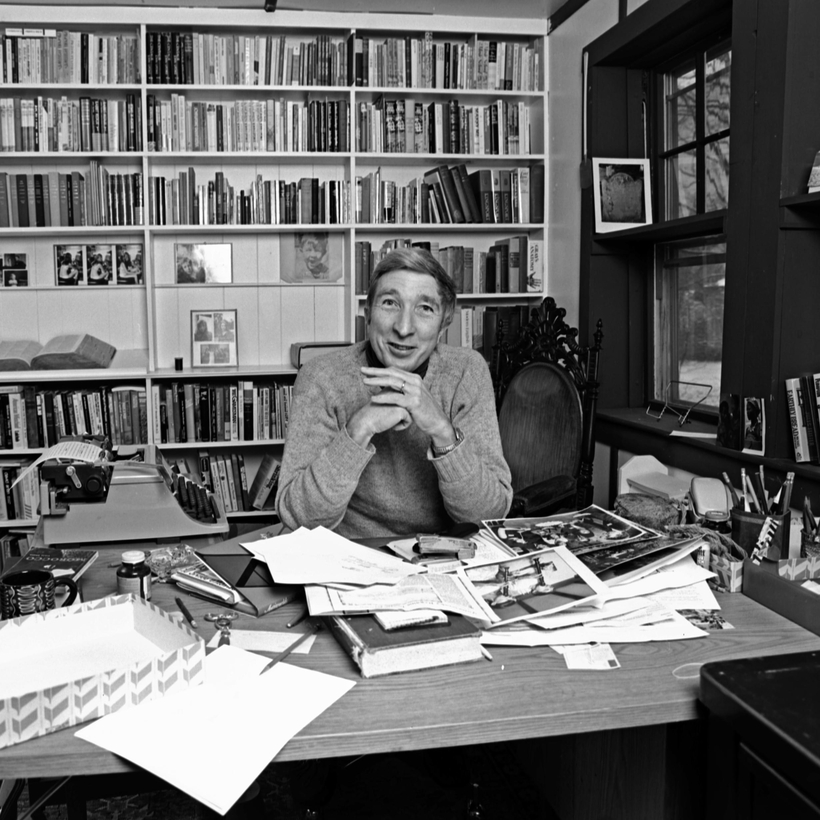

Early on in his prodigious career, John Updike began to bundle stacks of his personal papers off to the Houghton Library at Harvard, which eagerly collected them. Posterity on the installment plan.

It should come as no surprise that an author who produced a vast shelf of novels, story collections, essay collections, books of literary and art criticism, volumes of poetry, and a memoir should have written a lot of letters—more than 25,000, according to James Schiff, who has edited a new collection of Updike’s correspondence.

A fraction of the total, Schiff’s selection is still 822 pages long. At the outset, one feels a sense of fatigue and even dread about the climb ahead. By the middle, I was engrossed. And as I came to the last pages, I was surprised to feel a welling up of grief.

The reader is excited to witness the rapid ascent of the poor kid from Plowville, Pennsylvania, to Harvard and beyond. Updike’s letters home to his parents and grandparents are addressed, “Dear Plowvillians,” and Schiff informs us that they “became a source of entertainment and were often re-read” to friends and neighbors. His facility with details foreshadows the ease with which prose came to him as a novelist, the lapidary, graceful sentences that flowed and flowed.

After numerous tries, starting at age 13, Updike finally began publishing in The New Yorker during his senior year of college: first a poem, then a short story, then another. (New Yorker Kremlinologists will find much of interest in these letters.) He went on to publish more than 750 works of fiction, poetry, and criticism. But he was not free from the writerly self-doubt, and at one point he writes to his first editor, Katharine Angell, “I once saw a movie in which a chimpanzee, let loose in a laboratory, proceeded to mix, by accident, with his elbows, some sort of highly potent elixir. I know now how he felt when they wanted him to stir up a second batch.”

Updike handled his business affairs on his own, without an agent. In January 1968, he wrote to his publisher, Bennett Cerf, shortly after having gotten off the phone with him, to apologize if he sounded “too stupid, or unenthusiastic, or ungrateful for the financial wonders you were working under my eyes.” His 1968 novel, Couples, though still in galleys, had been sold to Hollywood for $400,000. “I feel the possibility of being rich is rather threatening,” he added.

Some of the most enjoyable letters are written to his peers in the what-gigantic-book-award-will-I-win-this-time sweepstakes: Philip Roth, John Barth, Joyce Carol Oates, Donald Barthelme, and so forth. To Don DeLillo, whose 1997 novel, Underworld, had just been published, Updike writes, “I enjoyed, by the way, the scraps of interviews with you that I heard over the radio when the publication of the novel had forced you out into the media arena. You managed to bring a dignity of long consideration to the ungainly business of thinking aloud.” Comparing the fraternal tenderness with which he addressed his literary peers to the relatively distant way he wrote to his children, I was reminded of Nancy Franklin’s line from her profile of Katharine White: “As an editor she was maternal; as a mother she was editorial.”

Midway through, the collection turns into a kind of novel: Updike’s marriage dissolves while an affair blooms. He writes to a friend that his wife, Mary, seems depressed; six days later, to Martha, the neighbor who becomes his second wife, he confesses, “My fingers smell of you.” The juxtaposition is jarring, comic, a little grotesque. Pure Updike, in other words.

In U and I, one of the great books of literary appreciation, Nicholson Baker writes that a “misleading momentum” often makes the endings of novels feel disappointing and “rushed.” In this regard, Selected Letters of John Updike excels at the opposite feeling: we have acquired an understanding of so many threads, and we are aware, by virtue of the thinning number of pages, that not just the book but the author’s life is coming to an end.

A letter to DeLillo after 9/11, which Updike witnessed from his son’s Brooklyn Heights roof, has a wistful tone absent from earlier exchanges. A note to David Remnick about Updike’s stage IV lung cancer is gracious and oddly steady, the voice of a man still unwilling to abandon poise. At one point, Updike fusses over a phrase from The Centaur—“the cloth seems all undone”—noting that it was a late addition, absent from the first edition. He calls the revision “fussing,” but his fussing was brisk, productive, a quick tug at the tie before heading out the door. Even in illness, he kept up the performance, reporting, reflecting, and smoothing.

One wouldn’t know from these letters that throughout his career Updike was the inspiration for reviews so splenetic they became noteworthy in their own right: Alfred Chester in Commentary (“a magician of surfaces”), David Foster Wallace in The New York Observer (“famous phallocrat”), Patricia Lockwood in the London Review of Books (“He wrote like an angel, the consensus goes, except when he was writing like a malfunctioning sex robot attempting to administer cunnilingus to his typewriter”).

Even a recent piece about the suburban novel by Adelle Waldman in The New York Review of Books tossed Updike aside (as opposed to John Cheever and Richard Yates), dismissing him as a merely descriptive writer. The letters don’t resolve the case; they extend it. Updike could be generous, self-mocking, priggish, smutty—all at once.

After 800 pages of chattering life with its sunny days and setbacks, closing the volume brings on a sudden quiet. As with his novels, the experience takes time to cohere, but when it does, one realizes Updike has built, line by line, an enclosed world. In these letters, as in his fiction, he never stopped trying to make life look composed, even as it came apart.

I felt a gratitude toward Updike at the end of this book that exceeded the feelings upon concluding one of his stories or novels. Maybe it was just nostalgia now that he is gone. Or maybe it’s that Updike’s industriousness, order, lyrical precision, and outbursts of libidinal energy now seem more attractive than they once did.

Thomas Beller is the author of several books, including J. D. Salinger: The Escape Artist and Lost in the Game: A Book About Basketball. His next collection, Degas at the Gas Station: Essays, will be published by Duke University Press next month