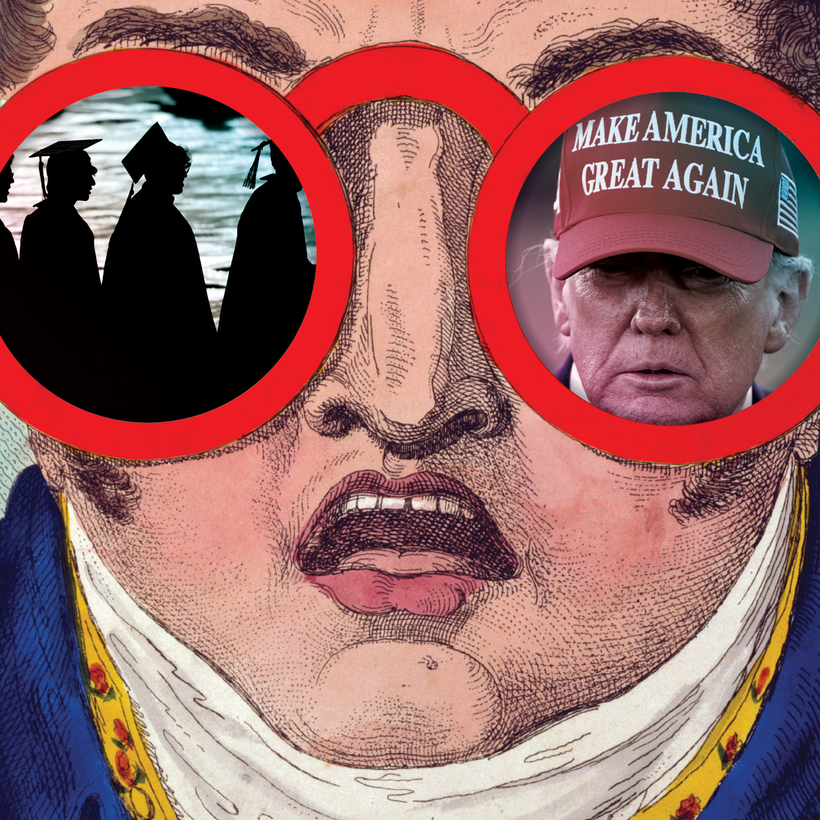

“It’s a Vichy, France, moment,” says Wesleyan president Michael Roth. “You wind up sliding back and back, appeasing the tyrant. And I don’t think that ends well.”

He’s talking about his fellow university presidents who have stayed silent during Trump’s ongoing assault on higher education. “They will not criticize the Trump administration because it’s in their immediate self-interest not to,” Roth tells me. “Hoping that they just won’t come for you seems to me immoral—and a mistake. But clearly that seems to be the calculation most leaders are making now.”

“Neutrality gave them cover,” says Jason Stanley, the Yale philosopher who decamped to Toronto after Trump’s re-election. “They could say they were principled. But it was just self-preservation.”

Mount Holyoke president Danielle Holley puts it even more starkly: “There is a right side and a wrong side of history. If you can’t defend the basic principles of higher education, maybe you shouldn’t be in higher education.”

At the start of this month, the Trump administration offered a list of nine colleges—Brown, Dartmouth, Vanderbilt, the University of Pennsylvania, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of Virginia, the University of Southern California, the University of Texas at Austin, and the University of Arizona—a deal that would give them special federal-funding treatment in exchange for signing on to a list of conservative demands, such as committing to strict gender definitions and monitoring employee speech. Schools have until Monday, October 20, to respond.

M.I.T. was the first to formally respond, rejecting the proposal, on October 10, followed by Brown, Penn, U.S.C., and U.V.A., with each school citing restrictions on academic freedom as its reasoning. That leaves four universities yet to reply: Dartmouth, Arizona, U.T. Austin, and Vanderbilt University.

This week, Trump opened the offer up to more than 5,000 universities via a Truth Social post that read, “Higher Education has lost its way, and is now corrupting our Youth and Society with WOKE, SOCIALIST, and ANTI-AMERICAN Ideology. ”

Schools that want to “return to the pursuit of Truth and Achievement” are “invited to enter into a forward looking Agreement with the Federal Government to help bring about the Golden Age of Academic Excellence in Higher Education,” wrote Trump.

The university presidents who have remained quiet in recent months have framed their silence not as cowardice but as “institutional neutrality,” a notion first articulated by the University of Chicago. Before October 7, 2023, fewer than 10 schools had such policies. Within months of Trump’s return to office earlier this year, nearly 150 did. (Some schools embraced institutional neutrality as students demanded they take a side in the Israel-Gaza war.)

In the 1960s, amid Vietnam War disillusionment and the civil-rights movement, university campuses across the country became a hotbed of protest. The 1967 Kalven Report, published by the University of Chicago, bore the central doctrine of institutional neutrality, concluding that while students and faculty are free to adopt political positions, the university itself should refrain from doing so, with rare exceptions when its existence is at stake—when “society, or segments of it, threaten the very mission of the university and its values of free inquiry”—or in extraordinary moral emergencies. Chicago has used the latter exemption to speak out a handful of times, including against apartheid in South Africa in the 1980s and against genocide in Darfur in the aughts.

“Kalven explicitly allows universities to speak when their core mission is threatened,” says Daniel HoSang, a professor of American studies at Yale. “There couldn’t be anything more germane than the threat of arbitrary funding cancellations imposed by the federal government. To stay silent is actually a betrayal of Kalven.”

A “Marriage of Convenience”

For decades, institutional neutrality was understood as protection from external interference by the state, the Church, and big business. The university, in Kalven’s words, should be “the home and sponsor of critics,” not a critic itself. Students could protest Vietnam or support the Black Panthers without worrying that their own university’s stance would chill dissent.

That consensus began to unravel in 2015. Trump launched his first presidential campaign. Black Lives Matter galvanized protests from the University of Missouri to Yale. Students demanded curricular reform, more diversity in faculty hiring, and the renaming of buildings whose namesakes had ties to slavery. A new vocabulary—“micro-aggressions,” “trigger warnings,” “safe spaces”—took hold. Commencements became battlegrounds: former secretary of state Condoleezza Rice withdrew from Rutgers in response to student outrage over her involvement in the Iraq war; Christine Lagarde, who was serving as the managing director of the International Monetary Fund (I.M.F.), pulled out of Smith College when students protested the I.M.F.’s “corrupt system” and alleged abuse of women.

Watching the culture wars creep closer to his campus, University of Chicago president Robert Zimmer asked law professor Geoffrey Stone to lead a committee tasked with updating the school’s traditions in 2015. The result was the “Chicago Principles.” On the surface, the document reaffirmed Kalven: speech must be protected, protest permitted, neutrality preserved. But its preamble, invoking “recent events nationwide,” betrayed a shift.

“The document presents itself as a response to a national crisis having to do with ‘free and open discourse,’” notes Anton Ford, who teaches philosophy at the University of Chicago. “The crisis was what came to be known as ‘cancel culture.’” The threat was no longer external power. It was internal dissent.

The Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE), founded in 1999 as a civil-liberties nonprofit, seized on the Chicago Principles. (The group changed its name to the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression in 2022.) Avowedly nonpartisan, it became in the last decade a de facto conservative advocacy machine in the view of its critics, such as Stanley.

Connor Murnane, chief of staff at FIRE, acknowledges that FIRE had a “marriage of convenience with conservatives,” but only because they were the minority in the faculty and student populations, and “free speech is a tool of the minority.”

FIRE elevated the Chicago Principles to orthodoxy. It lobbied trustees and lawmakers. Legislatures in Wisconsin, Arizona, and North Carolina mandated their adoption. By 2019, some 60 institutions had endorsed them; by 2024, the number surpassed a hundred. FIRE president Greg Lukianoff, with psychologist Jonathan Haidt, helped mainstream their mission with “The Coddling of the American Mind,” an Atlantic article which became a best-selling book, turning “snowflake” into a cultural epithet. Free speech, once a shield for progressive activists, was now the cause of their political adversaries.

“FIRE laid out the strategy for the Trump administration: create a moral panic about wokeness,” says Stanley.

Murnane disagrees: “We have always governed ourselves based on a singular principle: if it’s protected, we defend it.” For a number of years, that often meant defending conservative students or faculty, but now, he says, “we’re watching the pendulum swing back. The right is in power and they are flexing the same censorial tendencies.”

Now that FIRE is doing more to defend liberals, who find themselves out of power, its critics say that the organization has belatedly come to understand the real nature of the threat. But Murnane argues that FIRE’s values and agenda have never changed.

“The Trump-Friendly Ivy”

Historically, academic freedom enabled protest—teach-ins on Vietnam, rallies for racial justice. In recent years, the very language of free expression has been inverted.

Columbia University’s settlement with the White House required both University of Chicago–style neutrality and new restrictions on admissions and protest. “To the defenders of institutional neutrality, you’ve been telling us this was key to our freedom,” Ford says. “Has Columbia University just been liberated by the Trump administration?”

The shift is visible at Dartmouth, where Sian Beilock became the college’s first female president in July 2023. Within the first year of her tenure, she called in riot police to clear a pro-Palestinian encampment. Eighty-nine students and faculty were arrested. A viral video of 65-year-old history professor Annelise Orleck pushed to the ground provoked outrage. For the first time in Dartmouth’s history, faculty voted to censure a sitting president.

Beilock doubled down. “Part of choosing to engage in this way is not just acknowledging—but accepting—that actions have consequences,” she told the campus. When students later sought a meeting on S.A.T. requirements, they were greeted by security guards. Beilock testified in court against two who camped on the lawn of a Dartmouth administration building. Writing in The Atlantic in the fall of 2024, she defended her approach: “Appeasement can feel safe and easy—if that means giving in to the demands either of student protesters or of vocal donors.”

Now it’s Beilock herself who is being accused of appeasement. When Trump froze Harvard’s federal research funding, Dartmouth declined to join hundreds of other universities in signing a letter defending higher education, although Beilock sent a university-wide message in April, decrying “the recent threat to Harvard’s tax exempt status,” and signed an amicus brief supporting the school in June. “I like to speak in my own words,” explains Beilock, who says she does not “believe group statements are the best way to affect change.”

Beilock hired R.N.C. lawyer Matthew Raymer (Dartmouth ’03) as general council and forged ties with Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights Harmeet Dhillon (Dartmouth ’89), further reinforcing the school’s reputation as “the Trump-friendly Ivy.”

Critics saw hypocrisy. When she was president of Barnard, Beilock was one of six university leaders who co-authored a New York Times Opinion piece denouncing the overturning of Roe v. Wade. But at Dartmouth, neutrality appears selective for her: loud at moments of consensus, quiet at moments of genuine risk. (On Tuesday, the Chronicle of Higher Education cited two anonymous sources saying Beilock would not sign Trump’s compact as written, but Dartmouth has not formally responded to the White House.)

University of Chicago president Paul Alivisatos has invoked Kalven as cover. Vanderbilt University and Washington University jointly bought a full-page ad in The Wall Street Journal highlighting the schools’ commitment to “principled neutrality.” But the effect, Roth and others believe, is the same: a selective neutrality that justifies silence when speaking out matters most. Vanderbilt notably refused to join a number of other elite universities in signing a letter showing support for Harvard in its battles with the Trump administration.

What FIRE provided, critics argue, was the alibi. By elevating the Chicago Principles to scripture, it gave university leaders a way to call fear “principle,” ignoring the clear exception in the Kalven Report that requires schools to stand up for their mission. “They give people an excuse for not saying these things in public,” Roth says. And what they are declining to say, he adds, is nothing radical: “a defense of academic freedom itself.”

Beilock, for her part, would not directly answer whether she believes democracy is under threat—or if authoritarianism is on the rise.

Clara Molot is the Investigations Editor at Air Mail