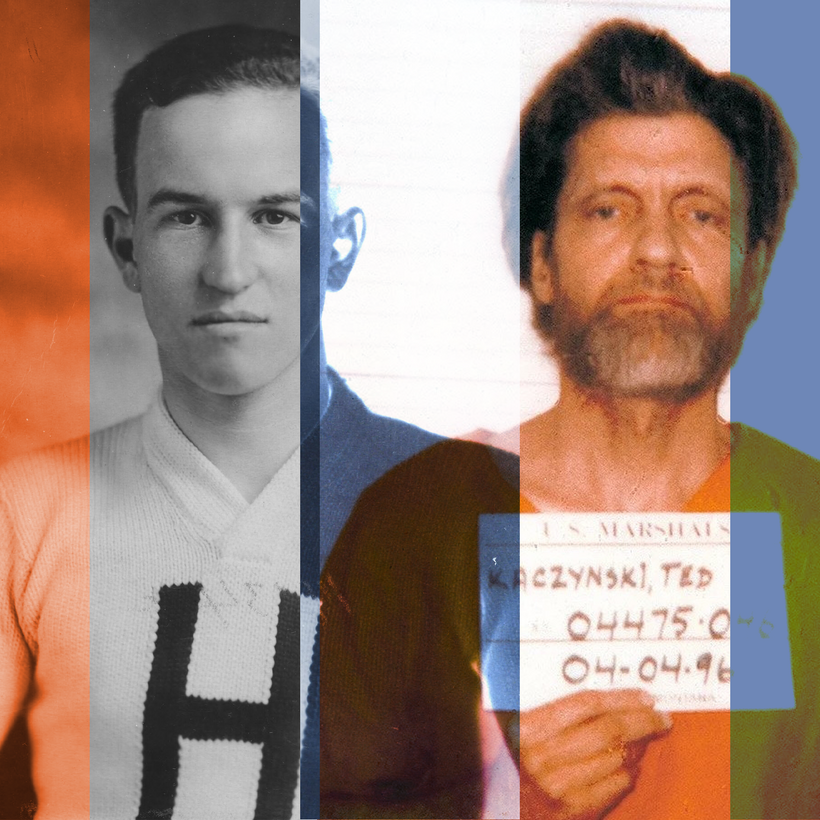

In the nearly three decades since the F.B.I. arrested Ted Kaczynski, outside his Montana cabin, the public’s fascination with his mind—its brilliance and its madness—has been revived every few years, most recently by Luigi Mangione in his four-star review of the Unabomber manifesto on Goodreads.

Those who have followed Kaczynski’s story closely may know that the late bomber was the subject of cruel psychological experimentation as a 17-year-old prodigy at Harvard in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Was this the trigger that pushed his psyche over the edge? I wondered this as I set out to research my new book, The Monsters We Make: Murder, Obsession, and the Rise of Criminal Profiling, in which Kaczynski is a key figure.