Three months ago, Jim Alterman posted a video on Instagram from his gallery, Jim’s of Lambertville in New Jersey, just across the river from New Hope, Pennsylvania, in which he “smashed” a work by Larry Rivers—once hailed as the “Godfather of Pop Art”—over his adult son’s head. “It was a student artwork,” Alterman clarified, part of Rivers’s estate and foundation holdings. “I wouldn’t smash a real Larry Rivers painting, but it looked good on social media.”

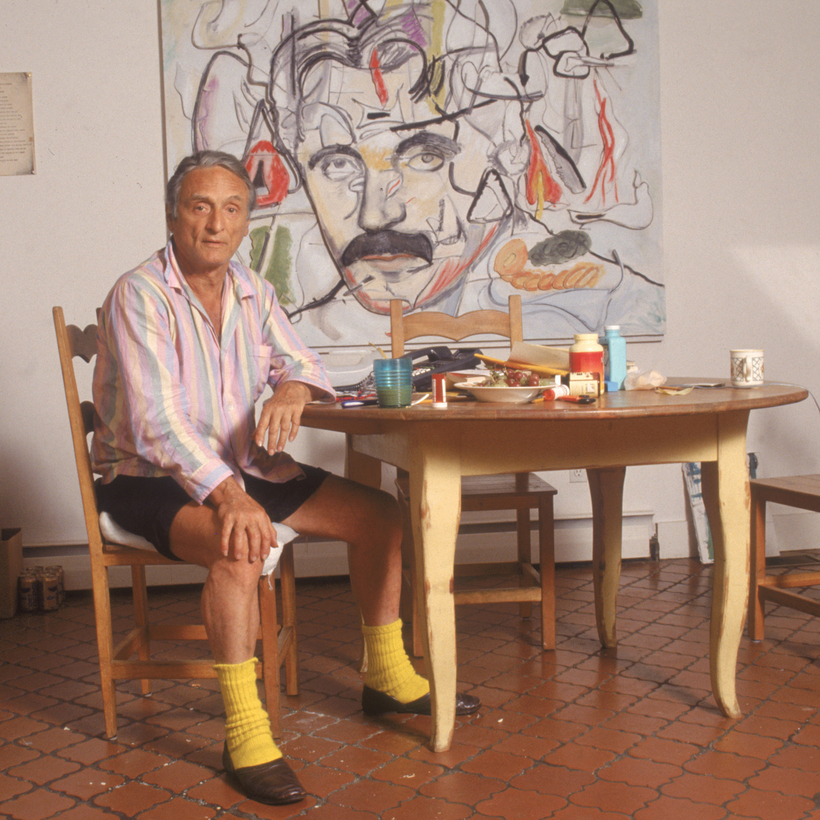

Rivers, who died in 2002, also loved to shock. His 1970 installation Caucasian Woman Sprawled on a Bed and Eight Figures of Hanged Men on Four Rectangular Boxes depicted a lynching; another, America’s No. 1 Problem (1967–69), displayed a Black and a white penis alongside a ruler. Offstage, he carried the same irreverence—serving cat food at a party and decorating a Christmas tree with tampons. He liked to cut the tops off his shoes to expose his toes.

That blend of humor and confrontation helped the New York–born artist re-introduce figuration into Abstract Expressionism, paving the way for the rise of Pop art. The Museum of Modern Art has featured his work in more than 60 exhibitions, including the seminal 2010 survey “Abstract Expressionist New York.”

Following the artist’s death, both an estate and a foundation were established on Long Island’s East End. The estate, led by John Duyck, a longtime assistant, and Rivers’s sister Joan Gordon, who died in 2023, managed sales from his studio inventory.

The foundation, directed by another former assistant, David Joel, with board members including Duyck, Gordon, Rivers’s son Steven, David C. Levy (the former director of the Corcoran Gallery of Art), and the historian and journalist Helen A. Harrison, held the most significant pieces and focused on organizing educational programs and exhibitions in collaboration with academic and art institutions.

But this summer, Larry’s youngest son, Sam Rivers, 40, discovered that all the assets of his father’s estate and foundation had been sold in bulk to Alterman—who usually specializes in lesser-known Pennsylvania Impressionist and modernist paintings—for just $300,000.

“I learned about the foundation sale in the strangest way: by reading the captions on Jim’s Instagram posts showing the works being moved, and realizing those pieces were gone,” Sam, who is unaffiliated with either entity, wrote to me in an e-mail. He noted that he had always understood the foundation’s assets were never to be sold.

Alterman’s Instagram video made viewers do a double take. It also raises the question of how the work of an artist of Rivers’s stature ended up in an obscure New Jersey gallery—without his own son knowing.

A River Runs Through It

Sam Rivers had long known his father’s estate was in peril, a fact allegedly confirmed to him by his older brother, Steven, 79, whose role on the board gave him insight into the foundation’s affairs.

Typically, estates and foundations work to enshrine an artist’s legacy by placing important works in major museums, but in Rivers’s case that never happened, leaving his market to drift.

“By the second year of my father’s estate being administered by the executors,” Sam tells me, “the money was already running out, and trouble with the I.R.S. had begun.”

Larry’s reputation didn’t help. In his 1992 tell-all, What Did I Do?: The Unauthorized Autobiography, written with Arnold Weinstein, he described his affairs with men and women, drug use, and his appetite for scandal—a persona that, over time, eroded his credibility. His 2002 retrospective at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., was, as The New York Times put it, “a very mixed success … with the late work feeling noisy and gauche, kind of embarrassing.” And in 2010, a damning Vanity Fair article alleged that in Growing—a film Rivers made with French filmmaker Michel Auder—the artist had exploited his teenage daughters by filming them topless.

Zack Wirsum, the senior vice president of the Chicago-based auction house Freeman’s-Hindman, stresses that bad press can be particularly damaging once the artist is dead. “It’s a challenge once the C.E.O. of the brand—the artist—no longer exists. Controversy can be a selling point when the maker can explain the intent. Once they’re gone, it can be a detriment, because it’s open to interpretation,” he says.

In a 2008 story for Artopia, the art critic John Perreault commented on the mishandling of Rivers’s legacy after attending an exhibition of his work in East Hampton.

“I was shocked that the show’s memorable Frank O’Hara Nude with Boots (1954) is not in some museum,” he wrote, “but still under the aegis of the Larry Rivers Foundation.” Was it, the article asked, due to Rivers’s troubled reputation or simple mismanagement? Perreault spelled out five steps that would help preserve Rivers’s legacy, including obliterating copies of What Did I Do?

It’s unclear how Perreault’s advice was perceived—or if it was heeded at all. In the 17 years since, Rivers has had only two solo shows in major institutions: at Rome’s Jewish Museum, in 2013, and at the Ludwig Museum in Koblenz, in 2019. The rest were small Long Island shows or individual works in group exhibitions, a thin record that points to the foundation’s failure to secure the kind of visibility that could have sustained his reputation.

In August 2024, Larry’s widow, Clarice, the mother of his daughters, Gwynne and Emma, died, leaving a trust worth about $1.4 million to be divided among all five of Larry’s children. But a tax lien—essentially a legal claim by the I.R.S. to collect unpaid taxes, first placed shortly after Larry’s death and hanging over the estate for years—meant the I.R.S. could seize the trust money unless the estate came up with cash.

In April of this year, Alterman stepped in, purchasing the estate’s assets for $300,000. The payment satisfied the lien, sparing the trust. Those funds will now cover legal fees and money promised to Rivers’s daughters, with the remainder divided among the five heirs. The family also retains the copyrights. Duyck, the estate executor, signed off on the sale.

Because the cash went straight to the I.R.S., the heirs had only been informed about the lien via conversations with Steven. For years leading up to that point, Sam alleges, his repeated requests for sales records and information on the estate’s tax liabilities were brushed off by the executors, Duyck and Gordon. His half-sister Gwynne described a similar pattern: Steven initially suggested she join the board, then quickly reversed course. “When I followed up with him, I got the sense then that he was told not to involve me,” she says. (Steven Rivers did not respond to AIR MAIL’s request for comment; Duyck and Joel declined AIR MAIL’s request for comment.)

Sam eventually tracked down a lawyer involved, and, in August, he viewed a bill of sale. He added that he was recently shown an inventory of what had been sold to Alterman, but that he and his siblings are still waiting for the legal document outlining the terms of the trust settlement.

That lack of transparency feels all the more jarring given what Sam was told years earlier. When he was 18, a lawyer and the estate board explained the will and the plan to make structured sales over time, with a 50-year goal of roughly $10 million. It was during this discussion that he came to understand the foundation’s art holdings were never to be sold.

The estate’s eventual insolvency was just as puzzling, given there could have been a market for Rivers’s work. As recently as four years ago, a painting from Larry’s “Africa 1” series went for $2.1 million at Sotheby’s. According to Sam, his brother Steven claimed that efforts to place the art with a museum, or even to hand it to the I.R.S. as payment, had fallen through. That left Alterman as the highest bidder, a resolution that, to Sam, fit the long-running pattern of mismanagement.

“[Rivers] served as a highly charged conduit between Abstract Expressionism and Pop art,” Wirsum adds. “It’s baffling to see his market stature not standing the test of time.”

Alterman, for his part, is eager to re-introduce Rivers by showing works that had long been hidden in storage. He tested the waters with a Palm Beach exhibition, which drew crowds. Now, owning the full inventory, he believes he can command prices more reflective of Rivers’s value. He also sees potential for sales in the L.G.B.T.Q.+ market, noting the artist’s own adventurous subject matter, but is waiting until art sales strengthen.

In the meantime, he’s learning more about the man. “He seemed like a funny character in person. He was nutty, off-color, and enjoyed pissing people off,” Alterman says.

Indeed. But Larry Rivers’s art was much more than that.

Roxanne Robinson is an American journalist who covers the luxury and fashion industries. She splits her time between New York and Paris