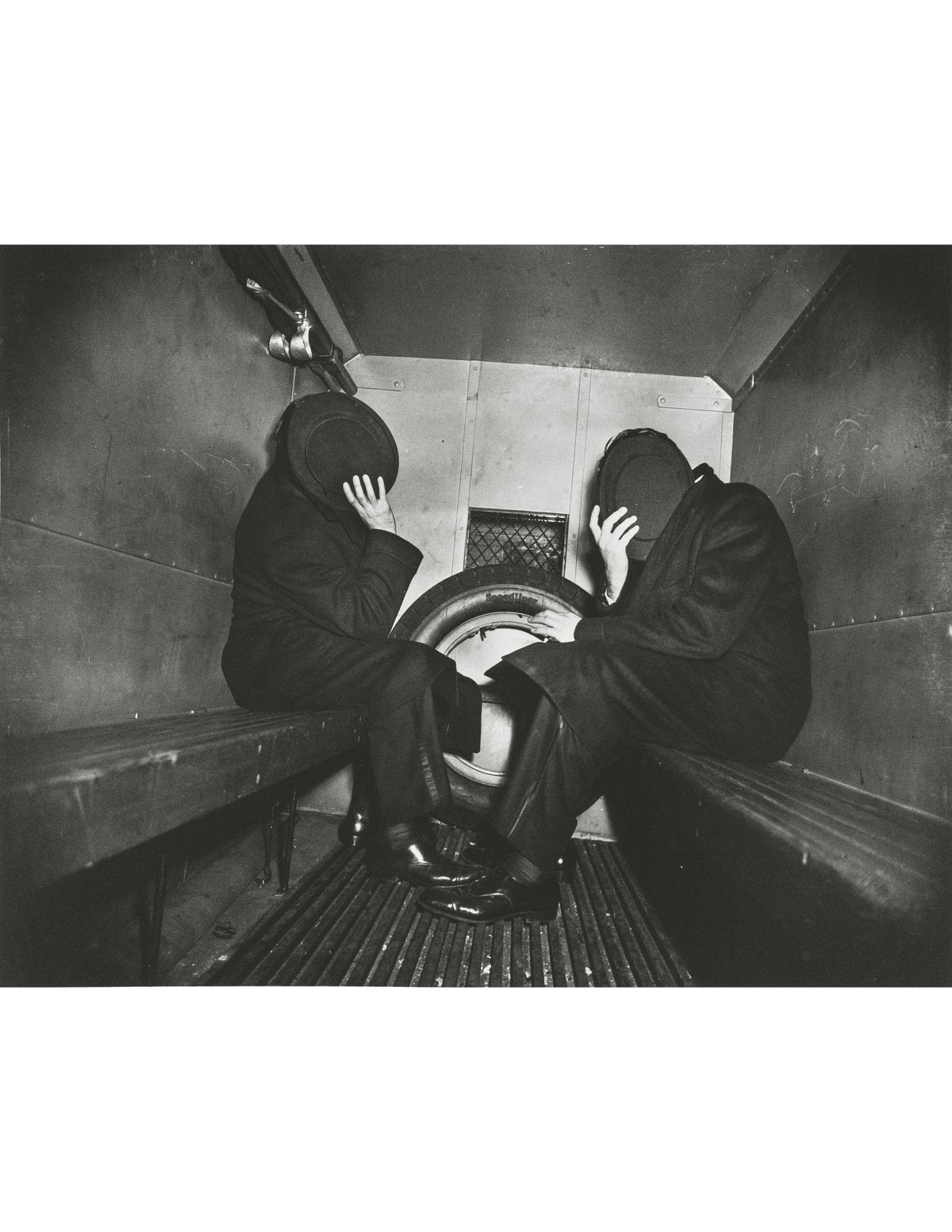

In 1935, when he was 35, Weegee started working as a freelance photographer in New York City. He’d gotten his hands on a police radio, which crackled day and night, and spent a lot of time in his car waiting for reports of murders, fires, and accidents. When they happened, he rushed to the scene and captured brutal imagery: gangsters face down, floating in pools of their own blood; mangled bodies in car-crash wreckage; criminals leering out of barred trucks on their way to prison.

Weegee was feeding a new beast. The tabloid press was on the rise, and his sensationalist pictures served it well. The New York Herald-Tribune, the Daily News, the New York Post, The Sun, and PM Weekly all bought in, and Weegee soon became well known.