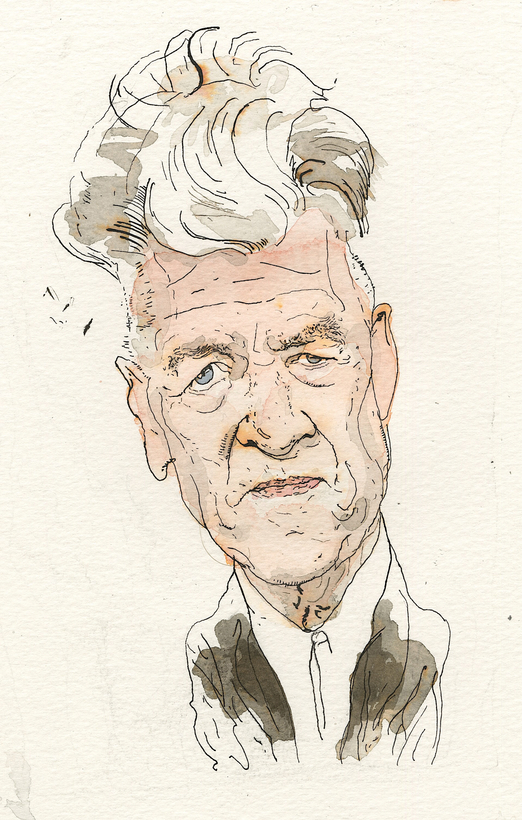

His nasal Midwestern cadence, earnest mien, and silver pompadour were as recognizable as Alfred Hitchcock’s voice, chins, and silhouette.

David Lynch’s onyx-dark but bizarrely comedic films were so recognizable that he joined the pantheon of greats before him: Hitchcockian. Bergman-esque. Fellini-esque. Spielbergian. Lynchian.