In 1986, the Cuban curator Ricardo Viera planned a group show at the Lehigh University Art Galleries, in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, on experimental Japanese photographers. His vision included works by both men and women, but the execution proved challenging. Collecting the men’s work, he was told, would be “politically difficult” due to cultural sensitivities. In other words, if Viera sought to include women, the men would withdraw.

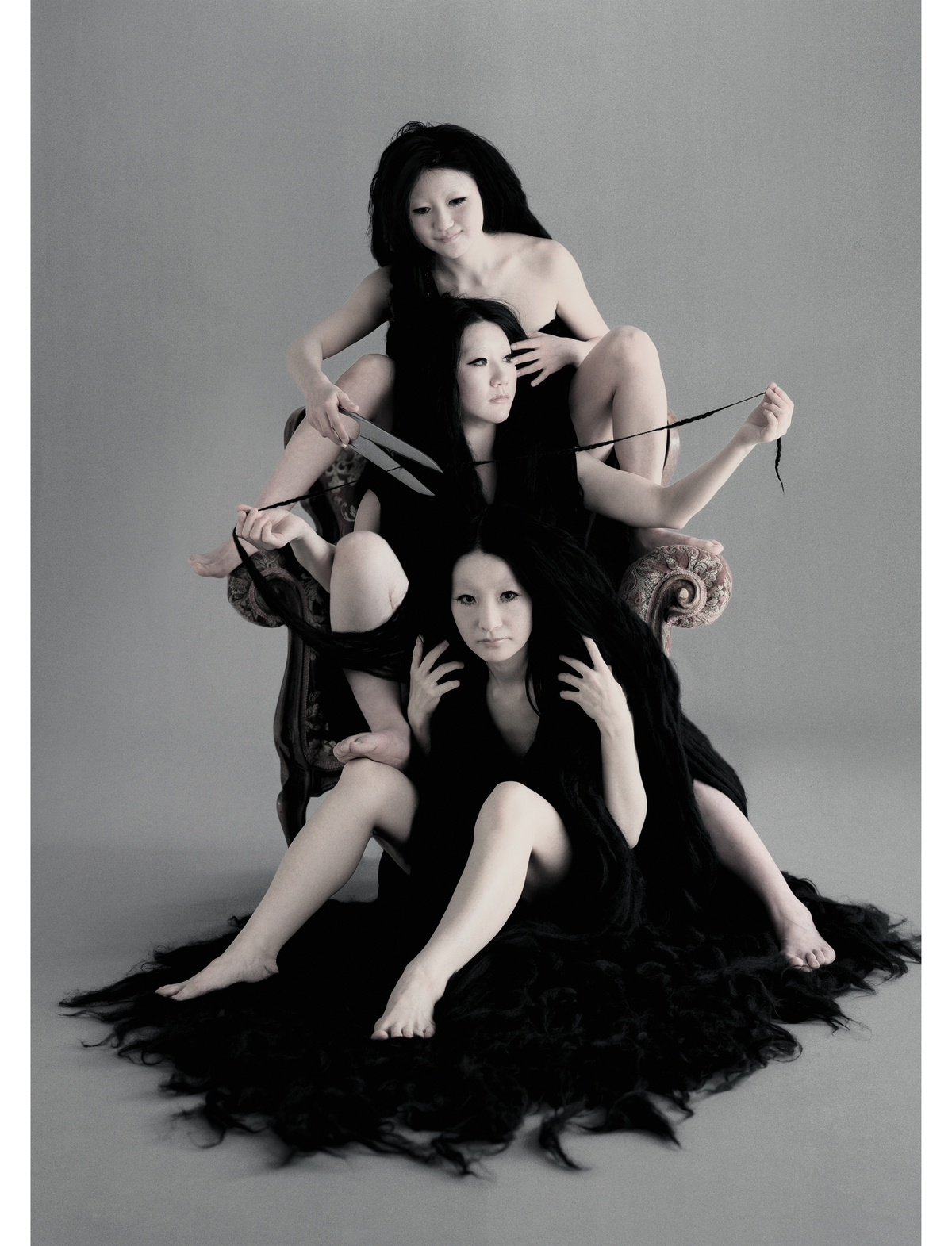

Viera chose the women. He rescheduled the exhibition for the following year and titled it “Japanese Women Photographers: From the 1950s to the 1980s.” Viera assembled prints by little-known pioneers such as Miyako Ishiuchi, Sachiko Kuru, and Mizuha Fukushima, and took inspiration from Ishiuchi herself, who had organized an all-women photography show 10 years earlier in Yokohama. (“I was 29 at the time,” Ishiuchi later said, “and felt I hadn’t been involved enough in the fight for equality.... To me, the exhibition was the stance I needed to take in order to become an artist.”)