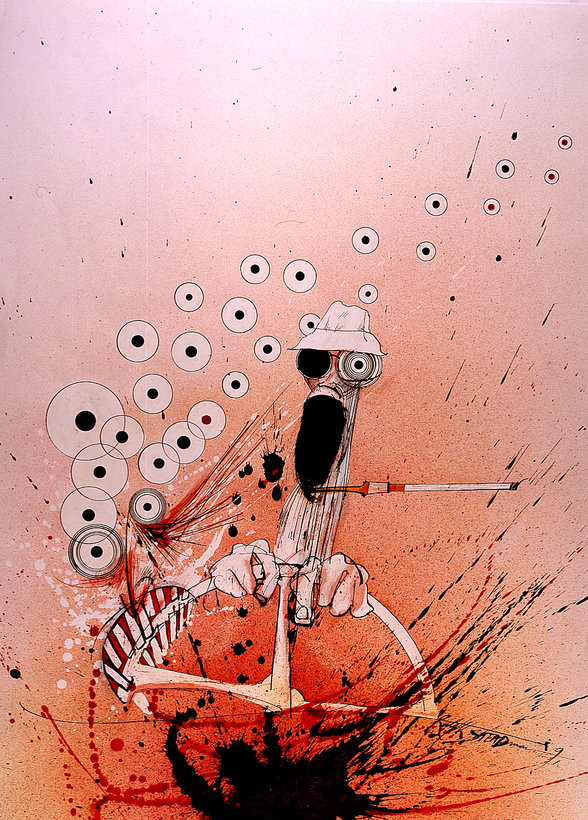

Throughout most of Hunter S. Thompson’s career, illustrator Ralph Steadman rode shotgun on the bending antennae of the author’s ragtop ’70s Caddy. Whenever fresh perdition ensued, he transmitted it to ink on paper.

Now admirers and initiates can see 149 of his works in a retrospective that spans 60 years. After a run at the American University Museum, in Washington, D.C., which begins today, it will travel to other institutions around the country.