Creditors had already seized their equipment. Uniforms were next. The 1974 Charlotte Hornets, members of the nascent World Football League, needed money desperately to keep the team afloat (and ensure its players weren’t competing naked).

So when the Hornets received a call from Tennessee-based investor Paul Sasso, they grabbed the opportunity. Sasso flew by private jet from Memphis to Charlotte, where he proposed a $100,000 cash injection for the franchise and pitched plans for a new stadium. Like most turns of fate in the W.F.L., it was too good to be true.

Within weeks, Sasso would be arrested by the F.B.I. and outed as career con man Paul Sassone. The private jet he’d flown—stolen. A few years prior, Sassone had entered the witness-protection program, only to be kicked out when his intel on the Mob turned out to be bogus. The swindler’s con was up when cops discovered his lifeless body in the trunk of a 1980 Buick in what many believe was a faked suicide attempt gone wrong.

“We had some run-ins with guys like that,” says Gary Davidson, one of the three men who challenged North America’s pro-sports monopolies by founding the American Basketball Association (A.B.A.), the World Hockey Association (W.H.A.), and the World Football League (W.F.L.) over a seven-year period in the late 60s and early 70s. And while these fledgling leagues dealt with their share of outlaws and sideshows, schemers and lawsuits, true talent also emerged.

Hall of Famer Wayne Gretzky made his professional-hockey debut in the W.H.A. Slam-dunk king Julius “Dr. J” Erving got his pro-basketball career started in the A.B.A. And famed quarterback Joe Namath may have begun his football career in the N.F.L., but he finished it in the W.F.L. Well, almost.

A Whole New Ball Game

Dennis Murphy grew up in Shanghai, the son of a Standard Oil executive. When Standard transferred Murphy’s father to the United States, they settled in Orange County, California, where Murphy became friends and classmates with Don Regan.

Like Murphy, Regan enjoyed an idyllic childhood. Later, at U.C.L.A., Regan met Gary Davidson, whose flowing golden hair and boyish good looks belied his broken beginnings. “My father left my mother four days after I was born. When I was six months old, he kidnapped me from Montana and took me to Idaho,” says Davidson. When he was two years old, the police negotiated a deal in which his father would return him to his mother with no consequences. His upbringing left him with a speech impediment and an unyielding desire to make something of his life.

By the late 60s, Murphy was carving out a career for himself as a politician, while Regan and Davidson linked up as law partners in Orange County.

The original idea was to bring a pro-football team to Anaheim. And as mayor of nearby Buena Park, Murphy was the key. But the 1966 N.F.L.-A.F.L. merger extinguished the Anaheim-football-franchise prospects. On a lark, Murphy suggested an alternative: start a pro-basketball league. It was an outlandish idea, considering the N.B.A. had reigned supreme since the 1940s, and had squashed or absorbed any threat of competition. But the apparent imprudence of such a ploy didn’t stop Murphy, Davidson, or Regan, who would go on to challenge the N.H.L. and N.F.L., two other powerhouse leagues that had been around since the 1920s.

There were no surveys, no focus groups, no market research—basketball was simply Murphy’s favorite sport, and Regan and Davidson were regulars at the Santa Ana Y.M.C.A. pickup games. But Murphy didn’t look the part of a basketball entrepreneur. “He could walk under a volleyball net without ducking,” says Regan. “But he was a real promoter, and Gary had a set of balls.”

The trio made it up as they went along. Up until then, the dominant pro leagues had grown complacent, benefiting financially at the expense of the hamstrung players who provided the product. It was a business opportunity with huge upside and little downside. “Dennis infected us with his enthusiasm about the project. Gary and I said, ‘What the hell, let’s take a shot,’” says Regan. “I was 33,” remembers Davidson. “I had no idea what I was doing, but I wasn’t bashful.”

“Dennis brought me and Gary to a meeting in Los Angeles with some money people who were interested in sports,” recalls Regan. A few months later, in early 1967, Regan, Murphy, and Davidson incorporated the league.

Their pitch to would-be owners proved compelling: buy an A.B.A. franchise for a fraction of the cost of an N.B.A. franchise, spend some money to lure talent, then force a merger with the N.B.A., slingshotting their investment tenfold in a few years.

Now backed by a consortium of deep-pocketed investors, the trio held a press conference announcing the inception of the American Basketball Association, featuring 11 charter teams located around the United States.

The televised event featured bikini-clad dancers serving whiskey, a harbinger of the circus that was to ensue. (Incidentally, the New Jersey Americans had to forfeit their playoff series against the Kentucky Colonels that inaugural season because the actual circus had priority booking over the Americans at the Teaneck Armory.)

With his arm in a cast and a sling, the result of a basketball injury earlier that week, Davidson was introduced as the league’s first president, while Regan was named its general counsel. Murphy held no official title but remained its chief promoter.

The dominant pro leagues had grown complacent, benefiting financially at the expense of the hamstrung players who provided the product.

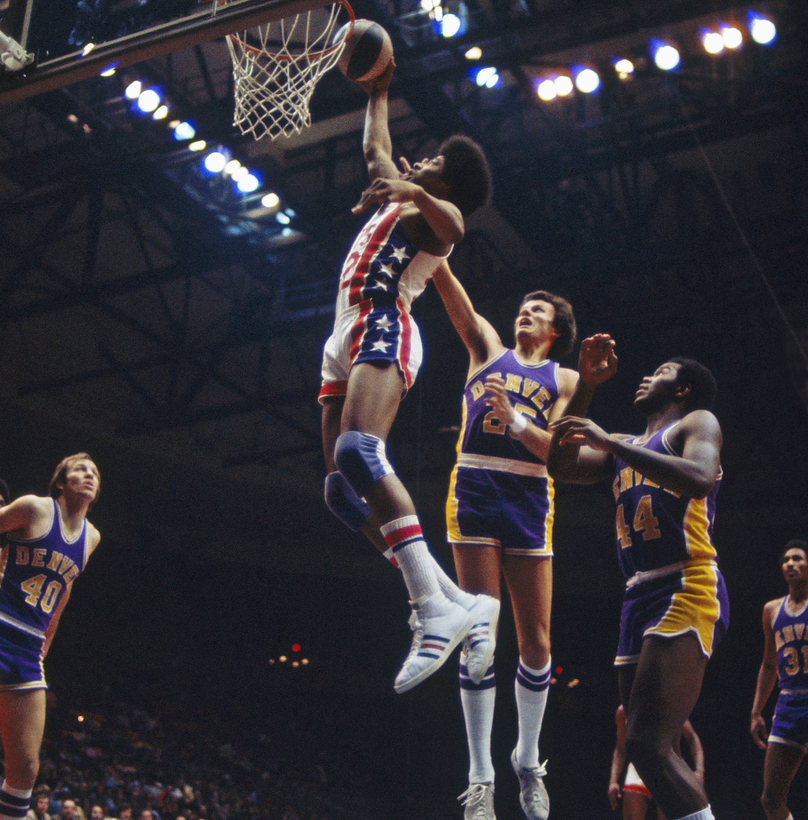

The three touted the A.B.A.’s innovations, such as the inception of the 30-second shot clock and the three-pointer. But the key differentiator from the N.B.A. was the red-white-and-blue A.B.A. ball. Despite some early issues with the dye running onto players’ hands, the multicolored ball became synonymous with the rebel basketball league.

More colorful than the A.B.A.’s ball were the players dribbling it. Indiana Pacers power forward Mel Daniels had gotten into Westerns during his college days at the University of New Mexico. After turning pro, Daniels bought a farm outside Indianapolis, where he and his teammates would dress as cowboys and ride around on horses. Players showed up to practice in chaps caked with mud and .45s in holsters. By midseason, management enacted a policy that all players’ guns had to be checked at the dressing-room door.

Off-court oddities aside, the A.B.A.’s talent pool was deep, in large part thanks to the shrewd maneuver by Regan, Davidson, and Murphy to poach N.B.A. referees. Until the mid-60s, N.B.A. referees were paid by the game. By offering seasoned professional referees a substantial pay raise and guaranteed annual salary, the A.B.A. legitimized itself with prospective players.

But the A.B.A.’s key initiative for luring talent was the Haywood Hardship Rule.

Spencer Haywood was the N.C.A.A.’s leading rebounder as a sophomore at the University of Detroit and a coveted pro prospect. But N.B.A. regulations at the time prohibited players from entering the league until four years after graduating from high school.

Haywood grew up impoverished, one of 10 children born to a single mother in rural Mississippi. Seeing an opportunity, the A.B.A. enacted the Spencer Haywood Hardship Rule, allowing undergrads to leave college for the A.B.A. before graduation if they endured financially dire circumstances. Haywood joined the A.B.A.’s Denver Rockets in 1969, where he would later be named the league’s Rookie of the Year and M.V.P. An undergrad exodus ensued as future stars including Julius Erving left college early to join the A.B.A. Once considered a novelty act by the N.B.A., the A.B.A. had morphed into a legitimate competitor, not only poaching players but entire markets, and cementing franchises across the U.S.

Meanwhile, Haywood challenged the N.B.A.’s regulation. The case went all the way to the Supreme Court, which ultimately ruled in his favor, paving the way for future undergrads to join the N.B.A. as well.

By the early 1970s, rumors of an A.B.A.-N.B.A. merger were swirling. Meanwhile, Murphy, Davidson, and Regan were plotting their next pro-sports endeavor.

Power Play

In the late 1960s, a pair of Canadian businessmen had their N.H.L.-franchise-expansion bid turned down. Having witnessed the success of the A.B.A., the businessmen approached Davidson, Regan, and Murphy with an idea to start a new pro-hockey league.

“We invited these Western Canadian guys for a meeting at the Balboa Bay Club, in Newport Beach,” says Regan. “We had a friend pull his 50-foot yacht up in the marina and hired a few of Newport’s finest-looking girls. The Canadians arrived Tuesday morning and were supposed to fly home Tuesday night. They didn’t leave till Friday.” By the end of the week, they had agreed on a structure for the World Hockey Association.

Like the A.B.A. at its inception, Davidson assumed the role of W.H.A. president; Regan, its general counsel; and Murphy, chief promoter. When it came to drafting their new players’ contracts, the trio quickly found that the N.H.L. player contracts were drafted slapdash—N.H.L. players were essentially indentured, bound to their teams by the reserve clause, which auto-renewed the player’s contract upon “expiration.” Average annual salaries hovered around $25,000, well below the average of those in the N.B.A., M.L.B., and N.F.L. Regan viewed these terms as not only feudal but downright illegal. “I sent one of the N.H.L. contracts to a trial lawyer, and he says, ‘It’s an interesting document, but it’s not a contract.’”

While Regan carved legal inroads, Murphy and Davidson crisscrossed the continent assembling ownership groups, using the same playbook they devised for the A.B.A. “We didn’t know a hockey puck from an Oreo, but we knew how to run a league,” says Regan.

Despite some skepticism—Canadian media dubbed the W.H.A. the “Wishful Hockey Association”—the inaugural W.H.A. draft went ahead, taking place at the Royal Coach Inn in Anaheim in 1972. No one was off-limits—Wendell Anderson, the then governor of Minnesota, was selected by the Minnesota Fighting Saints. Not to be outdone, the Winnipeg Jets used their 70th-round selection to draft Soviet premier Aleksey Kosygin.

And while some viewed the draft as a souped-up publicity stunt, the W.H.A. gained immediate credibility when it poached N.H.L. superstar Bobby Hull. Hull’s commitment paved the way for the W.H.A. to eventually sign legendary forward Gordie Howe and the 17-year-old Wayne Gretzky.

In practice and principle, N.H.L. players worked for the league. The W.H.A. flipped the roles. Regan’s new legal framework removed the constricting reserve clause and bent the rules for players—which in one case meant bending their actual sticks. (Hull liked a big curve on his blade, something deemed illegal by the N.H.L. but permitted by the W.H.A.)

“The Canadians arrived Tuesday morning and were supposed to fly home Tuesday night. They didn’t leave till Friday.”

The new league also encouraged players to unionize and granted a pension recognizing not just their W.H.A. tenure but also their N.H.L. And just as the Balboa Bay Club sunshine had helped secure initial funding to start the league, franchises across the Sunbelt lured top-tier players with the tropical lifestyle. Hall of Famer Jacques Plante finished his professional career in the W.H.A. and relished the team’s road trip to Phoenix so much he was forced to watch the game from the bench, unable to comfortably secure the goalie mask on his sunburned face.

In 1975 the Cincinnati Stingers emerged depleted following their road trip to play the San Diego Mariners, but not because of anything game-related. They arrived in San Diego with 22 players and left with 18. Two players had been arrested for fighting at a beachside dive bar. Another had crossed the border into Tijuana, and a fourth flat-out disappeared.

Some stories from this time were right out of Slap Shot. Or rather, the reverse: David Hanson, one of the triplets in the movie, played three seasons in the W.H.A.

In spite of the off-ice antics, the W.H.A.’s ingenuity and player-friendly practices solidified it as a threat to the N.H.L.’s dominance. While the N.H.L. mulled over its options, two of the three entrepreneurs were already on to their next project.

Moving the Goalposts

Fresh off their success in basketball and hockey, Davidson and Regan began eyeing the world of professional football and in 1973 founded the World Football League. Davidson, once again the league president, and Regan, its general counsel, then turned to marketing whiz Max Muhleman to round out the trio.

Within months of the formation of the new pro-football league, Muhleman had secured more than 100 signed marketing deals for the W.F.L. The looming 1974 N.F.L. strike meant that the W.F.L. was in a prime position not only to sign bona-fide N.F.L. veterans but also to secure lucrative TV contracts from Ted Turner, who was eager to broadcast more sports across the Southeast at the time. And now with a successful track record, Davidson and Regan courted a slew of wealthy A.B.A. and W.H.A. owners eager to snatch up pro-football franchises, notably Robert Schmertz, owner of the W.H.A.’s New England Whalers.

Aware of the W.F.L.’s increasing momentum, the N.F.L. took action. “They got people to track Gary and me, trying to dig up dirt,” says Regan. “I was staying at the Plaza and got word the N.F.L. hired a guy to pose as room service because they heard I was with a woman who wasn’t my wife. Sure enough, this guy knocks on my door and snaps a photo. They got a picture of me and my 12-year-old daughter playing gin rummy on the bed.”

As it turns out, the real dirt that would cause the W.F.L. to implode lay not with the league’s founders but with its franchise owners.

Just prior to launching the W.F.L., Schmertz, who had bought the New York franchise, suffered a brain hemorrhage. “He’s in the hospital and his wives, plural, show up,” says Regan. “His current wife gets in a fistfight in the hall with his former wife, and the former wife says to the current one, ‘You aren’t really his wife, because he married you before our divorce was final, so he’s a bigamist and you get nothing.’”

Within weeks, Schmertz, the linchpin of the league’s ownership consortium, was replaced. The franchise that originally planned to play home games at Yankee Stadium was forced to settle for a pseudo–football field on Randall’s Island, near the Bronx.

Then the Philadelphia-franchise ownership unraveled. “Grace Kelly’s brother was our owner in Philadelphia,” says Regan. “We find out his late father’s estate was such that Grace’s brother couldn’t sign a big check without his mother’s signature, so we had to replace him too.”

The real dirt that would cause the W.F.L. to implode lay not with the league’s founders but with its franchise owners.

Despite eight franchise shifts in the 12-team league, the W.F.L. kicked off in July 1974 and quickly began snatching up N.F.L. personnel. The Memphis Southmen (originally the Toronto Northmen), led by owner John F. Bassett, a Canadian mogul and businessman, made headlines by signing a trio of N.F.L.-ers to the then richest contracts in professional sports, at more than $1 million each.

The W.F.L. also recruited the N.F.L.’s youngest general manager, Upton Bell, to relocate Schmertz’s floundering New York franchise to Charlotte. “I knew the league had problems, but I said, ‘I’ll take a chance. I know the business, and I know the sport,’” says Bell. In short order, he convinced Arnold Palmer to purchase a stake in the newly branded Charlotte Hornets. “It was right out of a Hollywood movie,” says Bell.

But despite Charlotte’s stellar on-field play and near sellouts each game, Bell couldn’t shake Schmertz’s financial baggage. “I was getting calls from businesses around New York claiming Schmertz owed $15,000 here, $20,000 there. At one point, the sheriff showed up on a writ from one of Schmertz’s creditors to take the equipment and uniforms.” Bell’s lawyer talked the sheriff out of seizing the stuff until after the game had finished. Without uniforms or equipment, the Hornets, who had qualified for the playoffs, were unable to participate.

Schmertz’s bills weren’t the only ones Bell had to foot. “We’re playing the Florida Blazers, and the guy who’d taken them over had gotten involved with a drug dealer and had no money, so the team couldn’t pay its bills. But they had great players and a really good team.... We’d sold out the game because of them. We get a call from a judge who’s in a courtroom with the Blazers players, and the judge says, ‘There’s no way we’re going to let them play this game unless you guarantee their paychecks and their flights there and back.”

Bell arranged for the $60,000 payment by certified check. Then the Blazers walloped Bell’s Hornets in front of 20,000 fans. “Their quarterback thanked me after the game. It was the first paycheck he’d seen in months. I’d paid them to beat us. That was a first.”

After a shaky year one, the league enacted the Hemmeter Plan, which sought to stabilize salaries by tying them to a percentage of team revenues, shifting fixed costs to variable costs. Then the Chicago Fire franchise attempted to sign N.F.L. superstar Joe Namath. Their overture included changing the team colors from red to green and white, thereby allowing Namath, the former New York Jets star, to market his jersey in Jets colors.

“I knew the league had problems, but I said, ‘I’ll take a chance. I know the business, and I know the sport.’”

After learning that the W.F.L.’s TV provider insisted the league sign Namath or they’d discontinue broadcasting games, Namath demanded 15 percent of the entire league’s TV revenue. The league refused. Coupled with the peaking oil-shock recession of 1975, the W.F.L. was rendered insolvent.

The A.B.A., meanwhile, lasted nine years before merging with the N.B.A., in 1979, and the W.H.A. lasted seven before merging with the N.H.L. Murphy went on to found World Team Tennis (the first mixed-gender pro-tennis league), the International Basketball Association (for players six-foot-four and under), and Roller Hockey International. “I don’t know anyone that didn’t love Dennis.... And of the hundred people that knew him, I think Gary and me were the only ones who didn’t screw him. Everybody took advantage of him,” says Regan. Murphy died in 2021, at the age of 94.

Davidson and Regan continued practicing law together through the 2000s and remain close friends, both still residing in Orange County.

“I was supposed to have an aortic transplant today, but they postponed it to next week, so this is my pre-op celebration,” said Regan as our call wound down.

I thanked him for being so generous with his time.

“It’s only a thousand bucks an hour,” he replied. “You’ll get the bill tomorrow.”

Bill Keenan is the chief operating officer at AIR MAIL and the author of two books, Odd Man Rush: A Harvard Kid’s Hockey Odyssey from Central Park to Somewhere in Sweden—with Stops Along the Way and Discussion Materials: Tales of a Rookie Wall Street Investment Banker