One morning, around the year 1900, the Austrian artist Alfred Kubin sat down at his desk in Munich and pondered what to draw that day. Picking up his pen and a small piece of paper roughly five by seven inches, he sketched the figure of a naked, emaciated man, his hands tied behind his back. The man is suspended horizontally like a hammock, with his feet tied to the top of a pole while his head is held aloft by a stake through his mouth. A fire burns beneath him, scorching his belly black. Satisfied, Kubin titled the picture Torture.

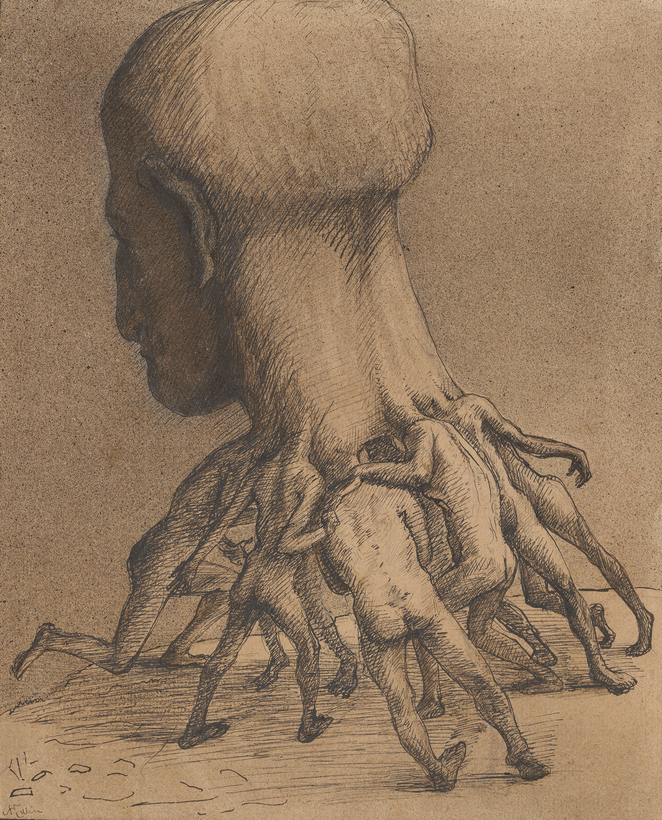

Torture is one of the thousands of nightmarish visions that Kubin drew across his long career. Beginning on August 14, at Vienna’s Albertina Modern museum, the exhibition “Alfred Kubin: The Aesthetics of Evil” invites the public to consider what drove the artist to such dark, even disgusting, corners of his imagination.