Midcentury architecture is synonymous with clean lines, floor-to-ceiling windows, and materials such as concrete and wood. It is characterized by austerity, having rejected the ornamentation of earlier styles. Furniture, objects, and textiles of the midcentury similarly prioritize functionality, organic shapes, and minimalism.

“Design is a response to social change,” George Nelson, a pioneering American industrial designer, wrote in the 1950s. In Europe, people were dealing with postwar rubble and black markets. In America, a glossy consumer culture was rising, and quantity, not quality, was becoming paramount. Much of the rest of the world was under the influence of Communism.

“Mid-century modernism,” the architecture critic Christopher Beanland has reflected, “with its brutalist concrete structures and austere lines, often leaves a legacy of buildings that can appear more oppressive than inspiring.”

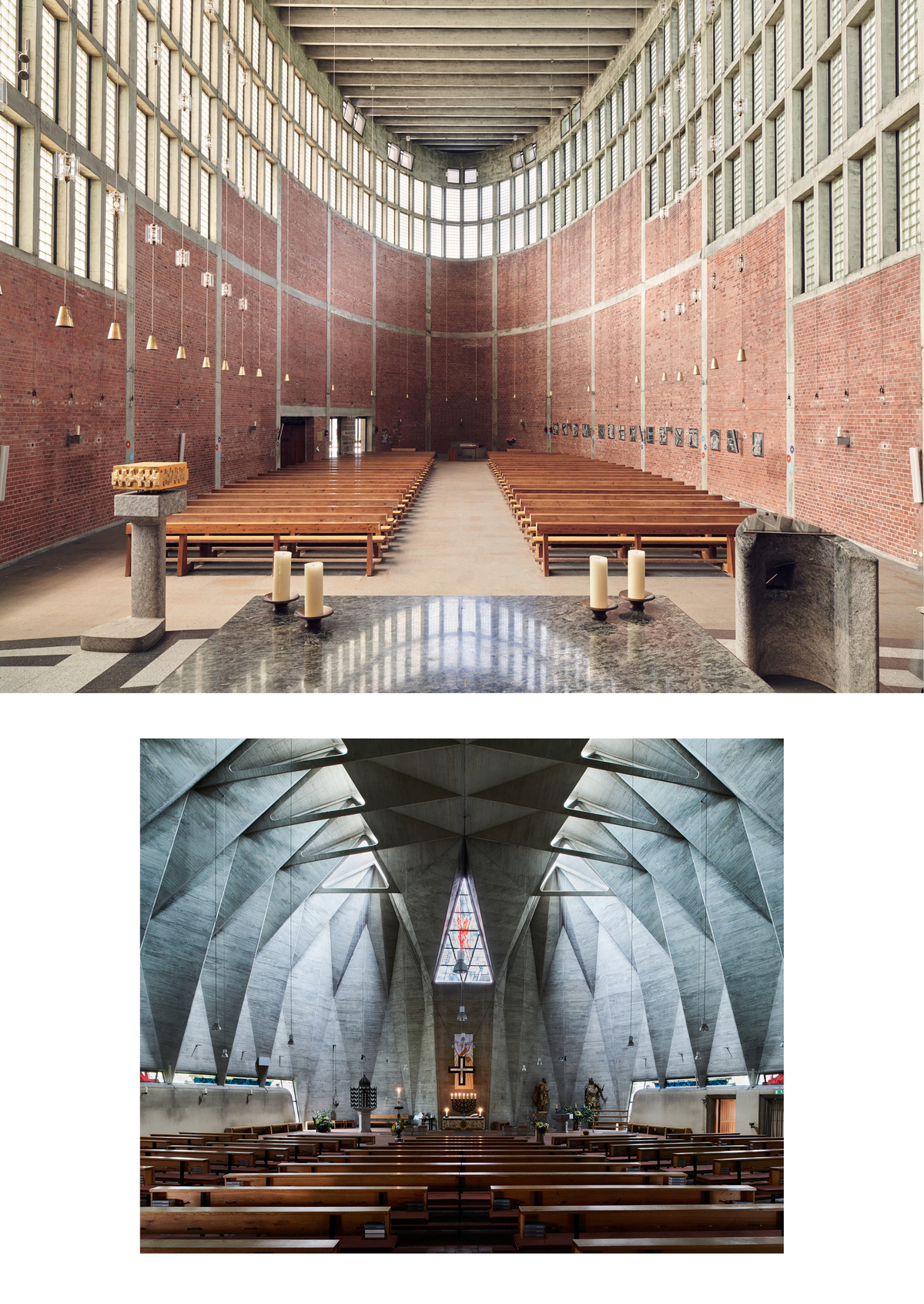

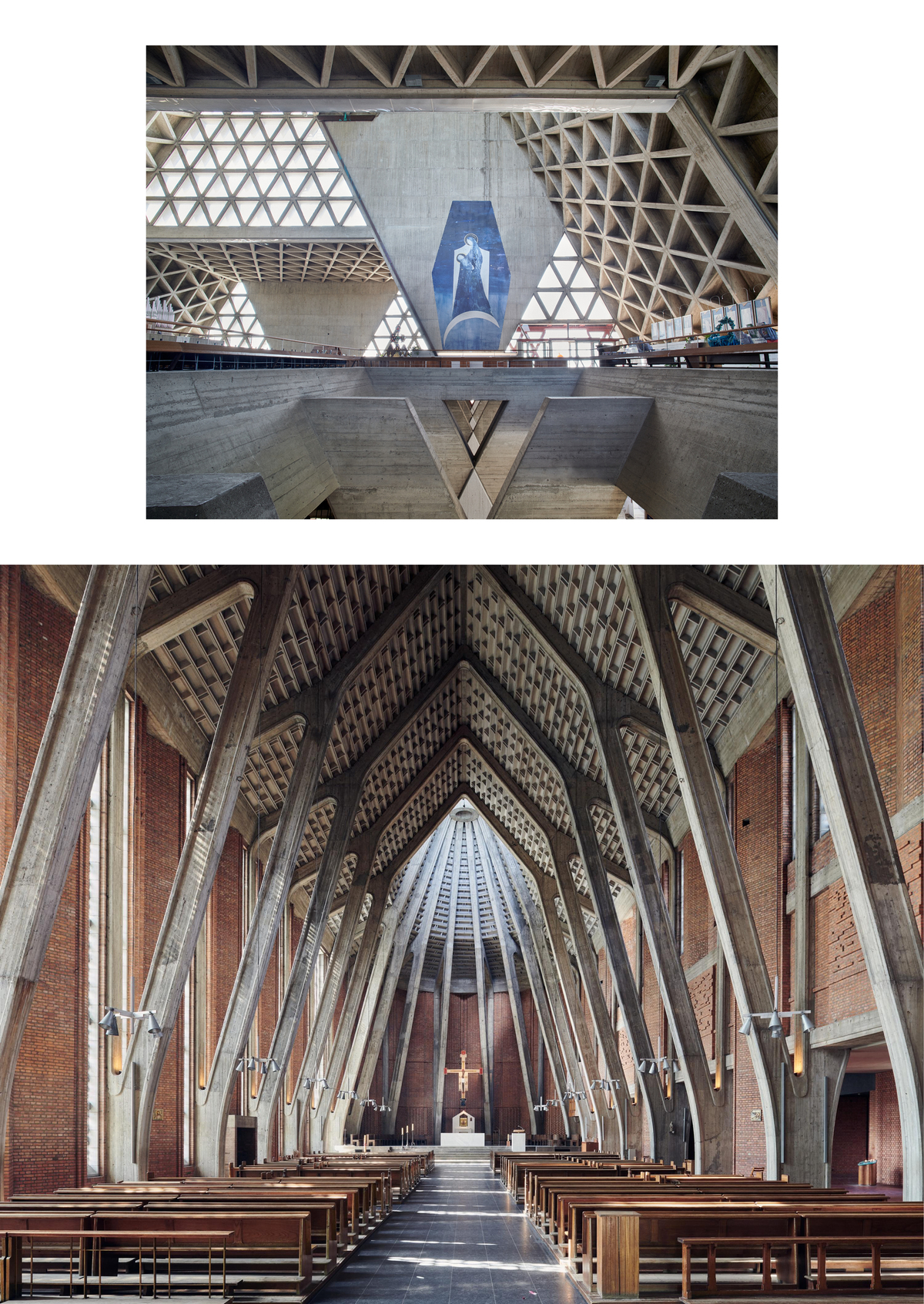

Enter Jamie McGregor Smith. In 2018, the British photographer traveled through Europe to look for markers of social change from past centuries. His investigation soon alighted on an interesting twist—modernist churches. During the pandemic, Smith chronicled these structures for his book, Sacred Modernity: The Holy Embrace of Modernist Architecture, just released. Among its subjects are brutalist giants such as St. Nicholas Church in Hérémence, Switzerland, a cubistic behemoth that towers over village chalets; and Kirche Johannes XXIII, Heinz Buchmann’s monstrous 1968 church in Cologne, Germany, which locals have both hated and adored since its construction.

Also out now is Cuban Mid-Century Design: A Modernist Regime, which was published in tandem with an exhibition at the Cranbrook Art Museum, in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. In the 1960s, a design revolution led by talents such as Clara Porset was underway in Cuba. Porset’s 1950s Butaque chair—a superb hybrid of Colonial-era Spanish design and pre-Colombian relics—would breed a new generation of artists. In the first comprehensive study of its kind, the volume examines nearly 100 works and includes seminal objects of functional design, architectural renderings, and speculative prototypes that evince a “design for all” ethos.

Both of these books, though differently focused, resonate with uplifting plans for a new world. “There is design in everything,” Porset said to her students. “In a cloud … in a wall … in a chair … in the sea … in the sand … in a pot, natural or man-made.” —Elena Clavarino

Elena Clavarino is a Senior Editor at air mail