A river runs through the personal saga of Robert F. Kennedy Jr. That river is the Hudson, or, in the language of the Indigenous Lenape, Shatemuc—the river that runs both ways with the tide.

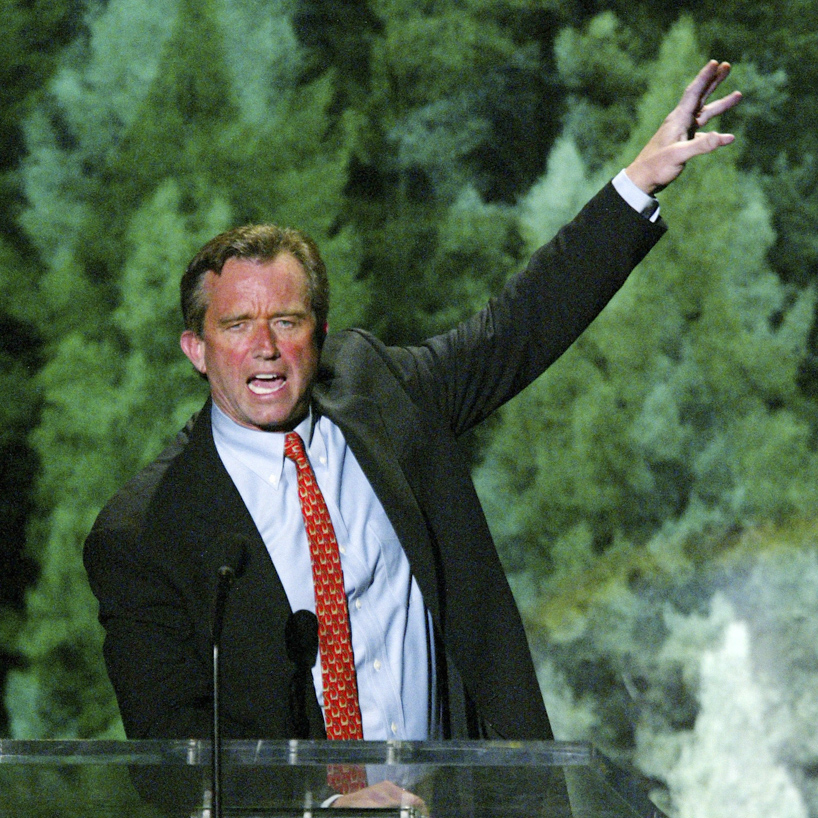

Kennedy portrays himself as a savior of the precious estuary. This narrative is central to his self-portrait, of a man who redeemed himself by overcoming his addiction and protecting and resurrecting the environment.

But those who interacted with him on the banks of the Hudson say the story runs both ways, too.

His environmentalism, they report, was often diluted by sloppy science, self-aggrandizement, and craven calculations about what funders would think. This led repeatedly to splits with close friends and colleagues.

In 2017 his departure from Riverkeeper, the environmental group he helped build on the Hudson, was publicly presented as voluntary. He was, in fact, forced out when his anti-vaccination views became too much for the scientists he had helped recruit to the group.

Unbeknownst to the team at Riverkeeper, the exact same thing had happened three years earlier at the Natural Resources Defense Council, where Kennedy had been a lawyer for 28 years. Officials in both groups acknowledge that in each case, it was done with no public recrimination against Kennedy. Until now, no one at Riverkeeper or the N.R.D.C. ever said a word in public about the real reason he left both groups.

“I don’t think anyone even wanted to tarnish Bobby,” a longtime colleague of Kennedy’s says of the break with the N.R.D.C. “He was tarnishing himself with all this vax stuff. People, to their credit, didn’t want to grandstand about it. The inclination was to be quieter about it. To disavow the substance of what he was talking about and to end the professional relationship. But to do that discreetly.”

Kennedy’s environmental colleagues have long harbored doubts. But they generally resolved their differences with him quietly. That is, until his run for president this year created a panic that he would be the spoiler who helped elect Donald Trump.

“A Shocking About-Face”

Little Island was the vision of billionaire Barry Diller. He and his wife, the designer Diane von Furstenberg, both live and work near the banks of the Hudson. Much of the riverfront in their neighborhood was derelict when, in 2014, they offered to build Little Island on the abandoned remnants of a historic pier.

Transatlantic liners docked there for more than half a century. The Titanic’s survivors returned to this place, and the Lusitania left on its last voyage from here. But by the 21st century, the pier was little more than rubble.

Along the Manhattan waterfront, work was underway to create a park where the liners and freighters once docked. Diller thought his island would make an excellent contribution to that park.

Little Island is hugely popular today. But at the time, many environmentalists saw it as a project that would draw money and focus away from the effort to build the new park along the river. Among these doubters were the staff of the environmental group Riverkeeper, which Kennedy controlled.

At times Kennedy has made it sound like he was the co-founder of Riverkeeper, a distortion that infuriates colleagues. But even they agree he played an essential role in building the organization, particularly as an awesome fundraiser who pulled in well-known actors for the group’s board and annual gala: everyone from Glenn Close to Edie Falco, Uma Thurman, Robert De Niro, and Leonardo DiCaprio.

Kennedy’s environmental colleagues have long harbored doubts. But they generally resolved their differences with him quietly.

The money Kennedy helped raise financed the organization’s aggressive lawsuits to protect the river from corporate polluters, nuclear power plants, and damage to the watershed that supplies New York City’s drinking water. Based on this record, stopping Little Island seemed right on mission to Riverkeeper’s staff.

The proposed site of Little Island was right in the midst of the stretch of Manhattan waterfront where, in 1985, environmentalists had won one of their greatest victories: they fought developers who wanted to intrude on the river and stopped the enormous Westway project. Westway, proposed in 1971, would have filled in acres of the Hudson from Lower Manhattan to 42nd Street and drilled an interstate highway through the landfill with apartments, offices, and parks atop it.

Developers and construction unions loved Westway. But a tireless environmentalist convinced a federal judge that the project’s impact on the Hudson estuary had not been properly considered.

Westway died, and was eventually replaced by a proposed park. This new plan would reconnect New Yorkers to the river rather than building over it. Advocates for the park saw Little Island as a breach of that commitment, an intrusion on the estuary offering activities such as concerts and dance that could as easily be offered on dry land.

Riverkeeper decided to sue. The group’s then president, Paul Gallay, asked Tom Fox to join them. Fox, as one of the Hudson River Park’s key advocates, had legal standing, Gallay told him. Fox readily signed on, and he brought with him Rob Buchanan, a teacher and boatbuilder.

Fox recounted what happened in several conversations with me and in his 2024 book, Creating the Hudson River Park: Environmental and Community Activism, Politics, and Greed.

“We met with attorneys and Riverkeeper staff to discuss strategy,” Fox writes. But then word of their plans leaked to the Hudson River Park Trust, which had been created by New York State to establish the Hudson River Park and which had accepted Diller’s gift of Little Island.

Then, Fox says, “Riverkeeper withdrew from the suit just three weeks before the filing deadline.” He calls it “a shocking about-face.”

What happened?

According to Fox, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and other members of Riverkeeper’s board objected to the lawsuit, under pressure from financial supporters of Riverkeeper who also supported Diller’s plan for Little Island.

“I was told that two of Riverkeeper’s major financial supporters, who had relationships with members of the trust leadership, threatened to withdraw their support, which represented approximately 7 percent of the organization’s $3 million annual budget—if Riverkeeper continued with the suit,” Fox writes.

Paul Gallay “was embarrassed and upset,” Fox says. “Their action was a shameful reminder of the disproportionate influence of wealthy donors.” For weeks the Kennedy campaign told me they planned to respond. They even asked for and received the key excerpts of Fox’s book. But, in the end, they never commented.

Gallay, who now teaches at Columbia University’s Climate School, won’t discuss the episode, other than to say his lawsuit was spiked by “a decision of the board” and not Kennedy alone.

At times Kennedy has made it sound like he was the co-founder of Riverkeeper, a distortion that infuriates colleagues.

That is largely a distinction without a difference, however, since Kennedy had consolidated his control over the board a decade earlier, after a collision with Riverkeeper founder Robert H. Boyle.

Boyle had been Kennedy’s mentor, taking him for trips on the Hudson to support his recovery from addiction. But they fell out when Boyle objected to Kennedy’s hiring of a scientist who had a criminal record for smuggling exotic birds.

Kennedy said the scientist deserved a second chance, but Boyle was adamant that his environmental crimes would undermine the group’s credibility. “Riverkeeper has always had clean hands when it went into court,” Boyle told The New York Times.

The fight ended in a board vote in 2000. Boyle lost, at least in part because other board members worried that the group would wither without Kennedy’s fundraising prowess. Boyle and seven other board members resigned.

”I thought he was thinking of himself and not the cause of the river,” Boyle told The New York Times. ”It all became his own greater glory.”

Boyle, who died in 2017, never got over what he viewed as Kennedy’s betrayal, his family says.

Kennedy had consolidated control. So it was not surprising that years later, the board supported him in backing out of the lawsuit to stop Little Island.

An Untenable Contradiction

Fox and his allies went ahead with the lawsuit without Riverkeeper, though he went back to the group more than once as the lawsuit moved forward. “We tried to solicit Riverkeeper to file an amicus brief and rejoin the fight, but they turned us down,” he says.

Eventually, Fox and his colleagues won a court ruling blocking construction of Little Island. Diller (an investor in Air Mail) pulled the plug, complaining that a “tiny group of people had used the legal system to essentially drive us crazy and drive us out.” At that point, then governor Andrew Cuomo, who is both a friend of Diller’s and an ex-brother-in-law of R.F.K. Jr., intervened and brokered a deal to resurrect the project.

Fox and his allies agreed to allow the island to be built in exchange for a commitment from Cuomo: the state would provide millions of dollars to complete the underfunded park, which would incorporate Little Island and stretch for miles in both directions. In effect, the lawsuit forced a compromise that seems to have served everybody.

But the question remains: Which side was R.F.K. Jr. on? Why did the self-declared savior of the Hudson abandon fellow environmentalists, and his own staff, at a crucial moment in a highly visible fight to protect the river?

“I think he separates himself from good science at times in order to aggressively pursue an issue and win.” This was said about Kennedy 25 years ago, to The New York Times, by a lawyer named George Rodenhausen. Rodenhausen represented Putnam County, up the Hudson, in negotiations with Riverkeeper about protecting the watershed.

It is true that environmentalists have often been tarred as unscientific by the companies and governments they take on. But in this case, Rodenhausen seems more prescient than partisan.

“I think he separates himself from good science at times in order to aggressively pursue an issue and win.”

As a member of Riverkeeper’s board, Joe Boren had sided with Kennedy in the retreat from the Little Island lawsuit in 2015. Boren was an expert on environmental risks and the chairman of Ironshore Environmental. He had actually become involved with Riverkeeper by contributing to one of Kennedy’s fundraising efforts.

But soon after the Little Island episode, Boren became chair and found himself with the challenge of easing Kennedy out of Riverkeeper altogether.

“He had two diverse opinions on science,” Boren says. “When it came to science behind vaccines, he said, ‘Don’t believe the scientists and the doctors.’ When it came to science on environmental things he said, ‘You’ve got to believe the scientists.’”

This contradiction had long been unsettling to the staff at Riverkeeper, Boren says, but it became untenable when Donald Trump was elected president in November 2016 and R.F.K. Jr. began to court him with his anti-vaccine message.

“I was the one who actually negotiated him out of Riverkeeper,” Boren says.

But the quiet way this was done allowed Kennedy to peddle a more self-serving version in public. In a profile earlier this year, The Washington Post described Kennedy as having retired from Riverkeeper. He did not. He was pushed out.

“The staff had a revolt,” Boren said. “We are a science organization and we don’t think scientists are off their rocker.”

Michael Oreskes is a co-author of The Genius of America: How the Constitution Saved Our Country—and Why It Can Again