Fifty years later, it’s difficult to convey the cataclysmic impact of Mikhail Baryshnikov’s defection to the West. In 1974, ballet was hot. The “dance boom”—the art form’s interval of unmatched popularity in America—was on. The Cold War with the Soviet Union was of nearly three decades’ duration, and the U.S. government had learned—well after the Soviets—how to incorporate classical dance into its image flexing. And then came an unforeseen windfall: the consummate classical technician, whose appearance onstage suggested an Icarus whose wings never melted, touched down on our side.

A star of the U.S.S.R.’s Leningrad-based Kirov Ballet, Baryshnikov had already proved a sensation on the Kirov’s foreign tours. It was just another night on the road—June 29, 1974—when the 26-year-old dancer, in Toronto as part of a small Russian touring group, left the theater after a performance and sprinted from his colleagues toward a waiting car.

All hell broke loose! There’s no better way to describe the weeks that followed. Baryshnikov’s defection was a news item—an uplifting one that unfolded in tandem with the death throes of the Nixon presidency. After some guest performances with the National Ballet of Canada, the blue-eyed Russian made his New York debut in July, with American Ballet Theatre, launching a 15-year association with the company that included nine years as its artistic director. The Balanchine ballerina Gelsey Kirkland announced that she would leave the New York City Ballet to be Baryshnikov’s partner at A.B.T.

“Misha,” to use the Russian diminutive his fans preferred, had already acquired the ability to inhabit space in an epic way, to seem much larger than he actually was. “You can learn how to look taller,” he told me in a 2010 interview. “You have to have air between your limbs. Because you’re small, you have to not move faster to hide it. You have to slow things down. You lift your chin and look beyond the balcony. ‘Oh, he sees something right there, that means he’s tall enough to see that.’”

Indeed, Baryshnikov opened up new vistas. And not just as a ballet virtuoso but also as a ballet director, an entrepreneur, a crossover star on Broadway and in Hollywood, and an arts impresario at his Baryshnikov Arts Center, in Midtown Manhattan.

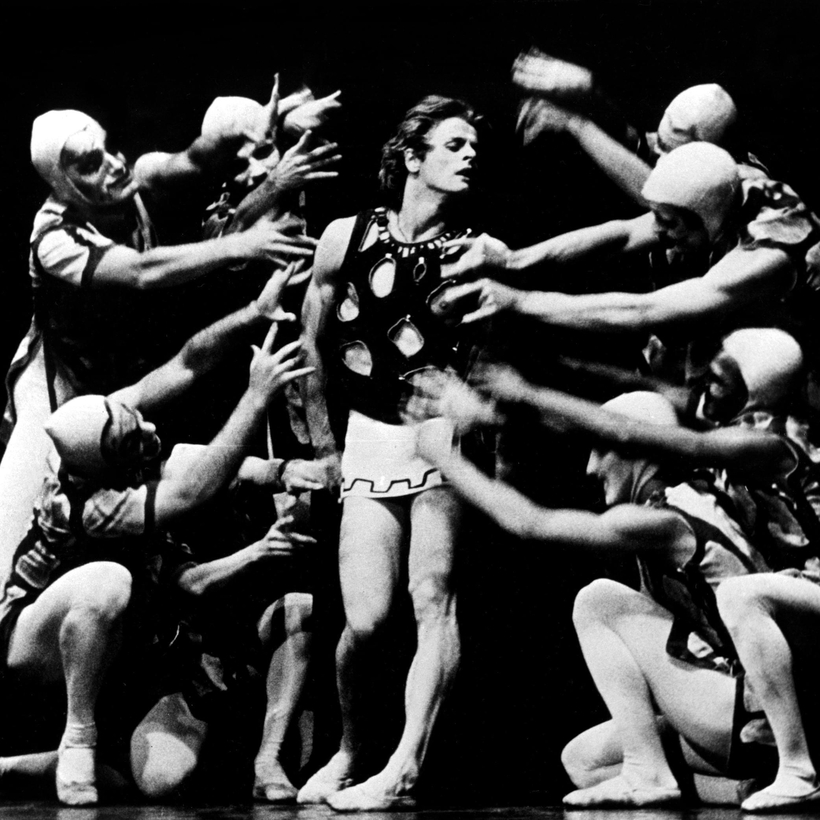

Great artists may diversify in infinite directions, and yet their earliest statements sometimes remain a tuning fork for their entire careers. At Moscow’s First International Dance Competition, in 1969, Baryshnikov won a gold medal performing a seven-minute solo, “Vestris,” created for him by Leonid Yakobson. Named for the 18th-century dance legend Auguste Vestris, the solo was a kaleidoscope of rapidly shifting moods and identities: male to female, mournful to jubilant, youth to age. He took the solo with him to the West, debuting it with A.B.T. in 1975. To this day, both performances (each is currently available on YouTube) transmit like a Rosetta stone.

As he matured, Baryshnikov increasingly conquered the ultimate movement frontier: not moving. Among his many guest appearances with different companies, he sampled the repertory of the modern-dance matriarch Martha Graham. As he wryly put it, Graham was “the queen of stand-up,” demanding that performers understand the metaphorical implications of monumental stillness. Her repertory, he recalls, requires the interpreter to ask himself, “What are you standing for? And who are you?”

We are still processing answers to that question, 50 years after a fateful June night in Toronto.

Joel Lobenthal is currently working on a biography of Diana Sands, the trailblazing Black actor of the 1960s