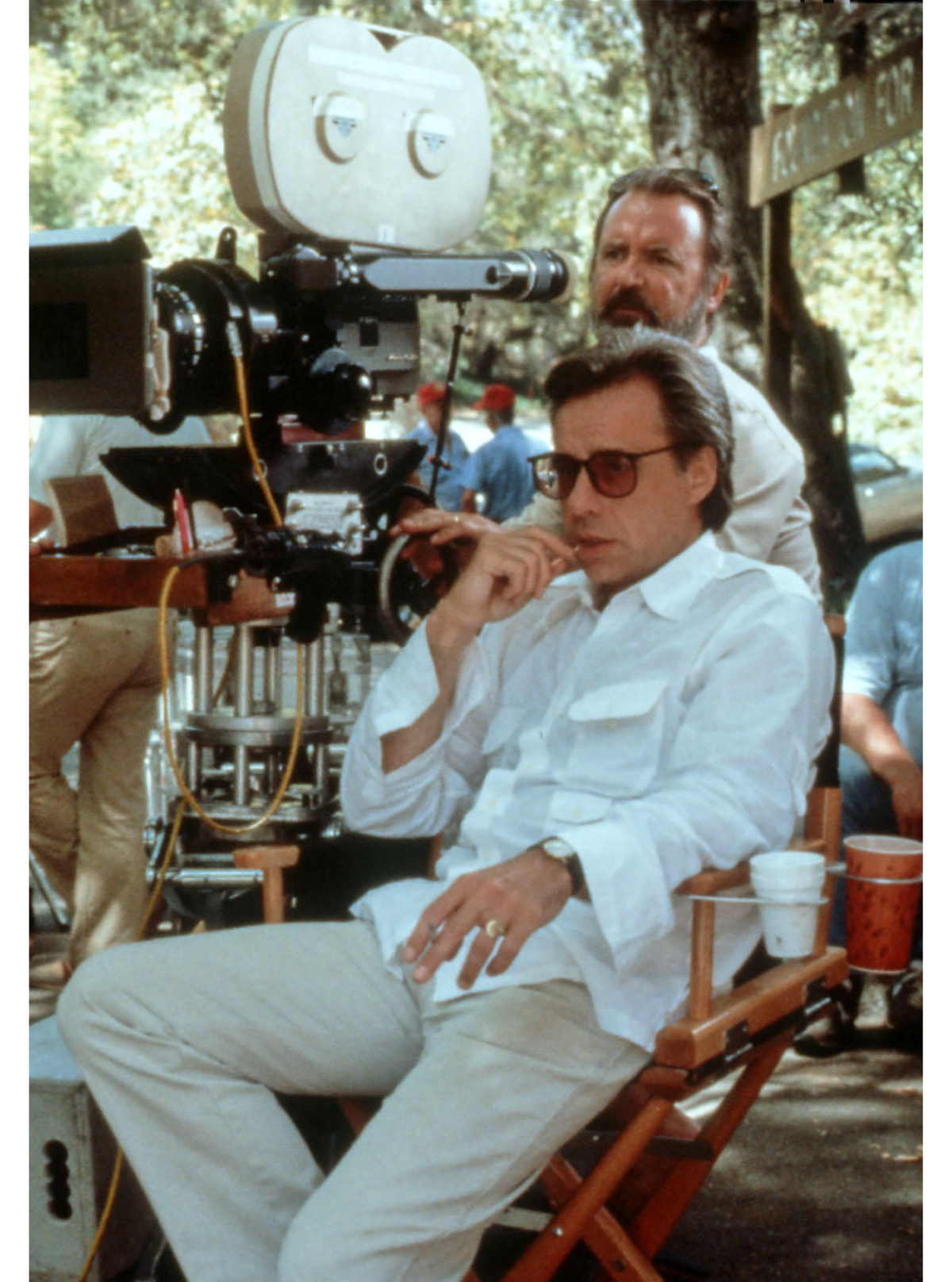

For proof that a director’s getup is symbolically important—even if he or she is mostly unseen by all but the cast and crew—one need look no further than Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse. The documentary draws on Eleanor Coppola’s own film footage of the Homeric trials, tribulations, and travails that beset her husband, Francis, as he thrashed through the filming of his 1979 Vietnam War epic, Apocalypse Now.

The production was notoriously fraught. The film was shot on location in the Philippines, where the set was battered by hurricanes. A drink-and-drug-addled Martin Sheen had a heart attack just after his 36th birthday, taking him out of action for a month. And Marlon Brando, who signed on to play a mythic, jungle-dwelling Special Forces agent gone rogue, was in the binge-eating and cue-card-reading chapter of his career. All of this is writ large in Eleanor’s home movies from the 16-month shoot. (It was originally scheduled for a few months.)