In 2007, an amateur historian and flea-market enthusiast named John Maloof purchased the contents of a storage locker—sight unseen—at auction. It contained approximately 150,000 prints, negatives, transparencies, and rolls of undeveloped film. This stash was the work of a professional nanny who was obsessed with photography but who chose to show her pictures to no one. Her name was Vivian Maier, and after Maloof’s astounding discovery of her oeuvre she was soon acclaimed as an important 20th-century artist. On May 31, Fotografiska New York becomes the first institution in the United States to present a major retrospective of Maier’s work. Offering a complex portrait of this enigmatic figure, who died in 2009, the exhibition includes more than 200 photographic prints, Super 8 footage, and sound recordings.

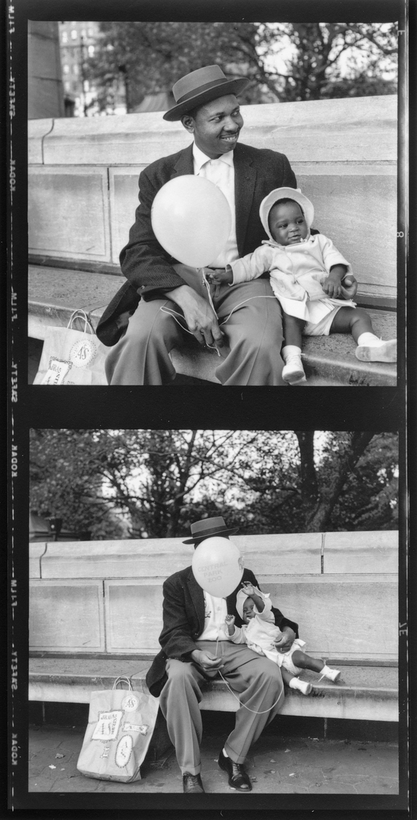

While biographical information on the mysterious Maier is scant, we know that she was born Vivian Dorothea Maier in 1926, in the Bronx, New York. After her parents separated, and when Vivian was still young, her mother moved them to her native France, where her daughter began to hungrily document the world with her cardboard Kodak Brownie. In 1951, Maier came back to New York and the next year procured a twin-lens Rolleiflex. With the square-format camera held inconspicuously at hip height, she flourished photographically.