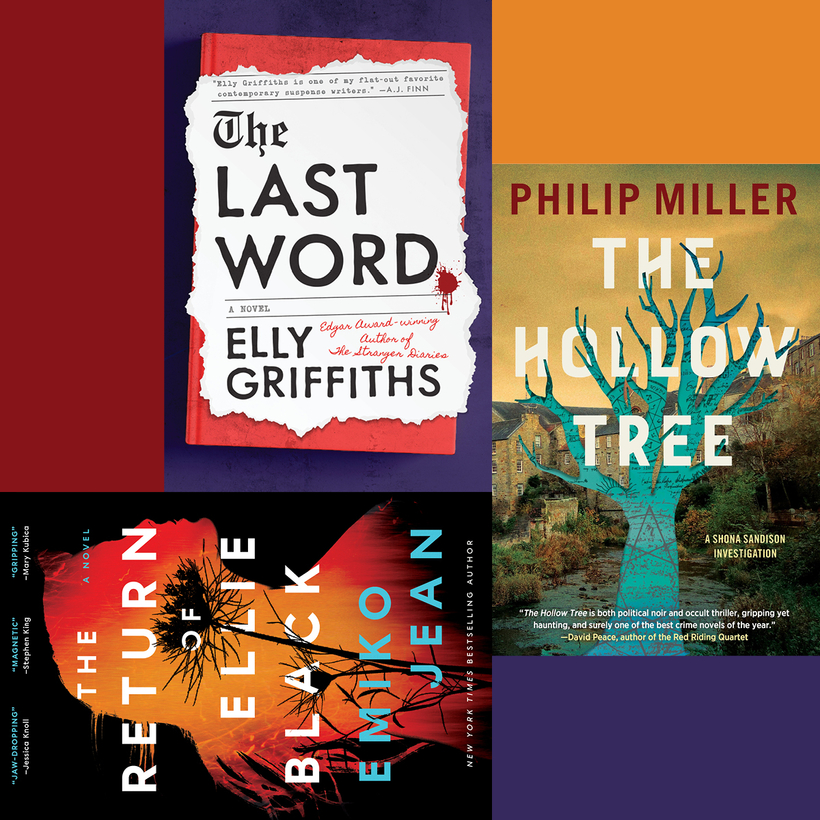

When five spooked horses from the Royal Household Cavalry threw their riders and bolted through the streets of central London last month, it was a reminder that although England is an ancient and highly developed civilization, a primal wildness always courses beneath its polite veneer. The fallout from such escapes is the subject of Philip Miller’s The Hollow Tree, where the gloom and brutality of centuries past hang heavy.

Shona Sandison, the irascible Edinburgh journalist from Miller’s elegantly noir-ish The Goldenacre, returns here, to attend the wedding of a friend from the newspaper where she once worked. She’s now a “churnalist,” cranking out copy for an agency that specializes in investigative pieces, one of her few options in a world where newspapers are disappearing.