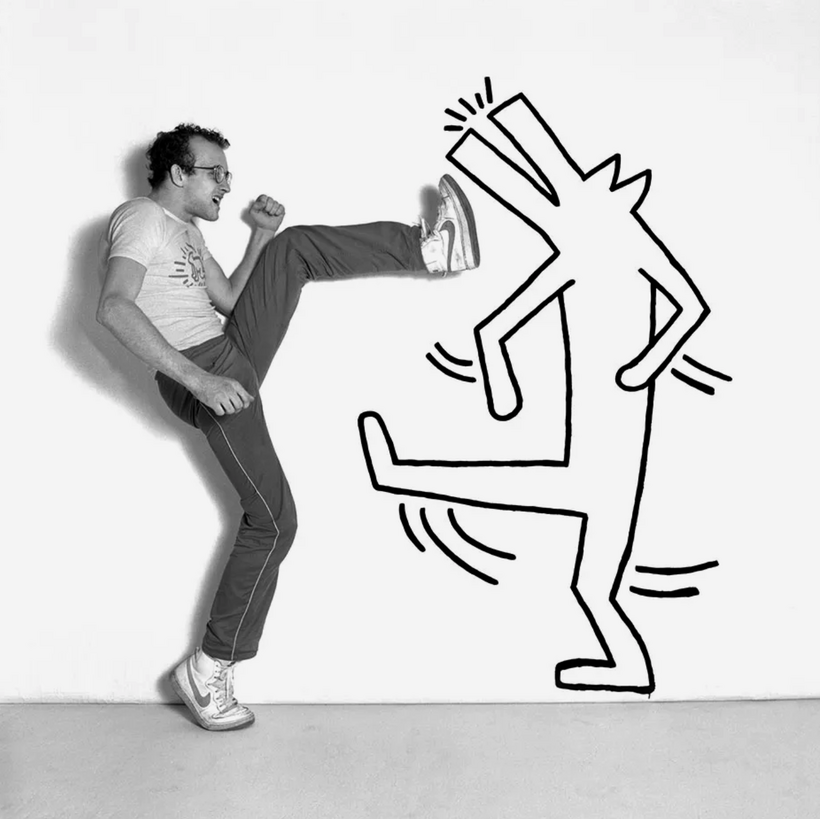

In the space of little more than a decade, Keith Haring lived a rich and improbable life. He was still just a student in New York when he developed the ingratiating version of street art that would make him a surprise star of the 1980s art world, pop-culture division.

His first examples were mordantly funny notes from underground, thousands of white chalk drawings he made in subway stations. Haring laid them down quickly—transit cops were around every corner—on the sheets of black paper that once covered expired station ads until new ones could be pasted into the same frames.

His radiant crawling baby, the flying saucers zapping barking dogs, the faceless figures waving their arms in the air, usually emanating a force field of short lines—Haring’s recurring cast of excitable characters grew over time into a full lexicon of comic exuberance and comic menace. Looming out from murky subway stations, they could even seem like bulletins from the collective unconscious, if the collective unconscious had a sense of humor and 100 or so citations for subway vandalism.

In the early 1980s, it could seem there was a Haring in every New York station, especially the ones that served the hipster East Village and the gallery-land of SoHo, proximity that soon made them cherished hieroglyphs of the downtown art scene.

From there it was a quick leap to actual galleries in New York and across Europe. And also into a social stratosphere where Madonna, Yoko Ono, Dennis Hopper, and Brooke Shields were all on his buddy list, along with the inevitable Andy Warhol, now past his prime as listless ringmaster of his boho-glam Factory and happy for whatever street cred younger artists such as Haring could lend him.

A devoted club kid—the Paradise Garage was his mother church—Haring also threw himself annual birthday dance bashes that attracted Richard Gere, Diana Ross, Grace Jones, and Bianca Jagger, plus whatever hot strangers he just pulled in off the street.

The good times might have lasted forever if something else had not arrived in New York around the same year Haring did—the AIDS virus. In 1990, when he was just 31, it would take his life. So Brad Gooch’s thorough account of Haring’s brief time is mostly a tale of head-spinning ascent, until it drifts down into a melancholy twilight, though one made bearable by Haring’s refusal to let mere death get in the way of his life’s work. As he once wrote: “ART IS CHANGING. … I FEEL IT SEE IT. I AM PART OF IT.”

The good times might have lasted forever if something else had not arrived in New York around the same year Haring did—the AIDS virus.

Haring was born in 1958 in Reading, Pennsylvania, and raised in nearby Kutztown, where his father, an electronics technician and amateur cartoonist, taught him to draw. After high school, he spent two years in Pittsburgh attending a small arts school. But by 1978 he was where he really belonged, in Manhattan, to start classes at the School of Visual Arts and, not incidentally, to join the priapic scrum that was New York gay life in the years before AIDS, a setting both liberating and, as it would turn out, lethal.

A nerd’s nerd, Haring had a Woody Allen–ish face perched on a string-bean frame, but also a roaring libido. He would always be insecure about his looks, but not so insecure that he didn’t score like a jackrabbit. Meanwhile, he also somehow found energy for two long-term boyfriends, both good-looking Afro-Latinos, his forever type. Both were named Juan.

Haring wasn’t really a graffiti artist. Graffiti-adjacent is more like it. He borrowed the taggers’ idea of hit-and-run public-image-making but used it to create a universe, a Disney-esque theater of players in some slapstick apocalypse. And while Fab 5 Freddy and Futura 2000 were “bombing” whole train cars with their street names, Haring was more of a stealth bomber. He didn’t even sign his subway pictures.

Plus, he could draw. However cartoonish, his line was fluent and unhesitating. Once he started working at wall-size scale, often on the 12-by-12 vinyl tarps that he liked because they had no art-historical associations, older Pop luminaries like Roy Lichtenstein and James Rosenquist would marvel at his sheer dexterity, his ability to lay down dense compositions with no preparatory drawing, just a straight shot from brain to hand.

Haring had his contradictions. Intent on being a “people’s artist,” he did many murals at no cost, mostly for schools and hospitals. And as the Reagan years dragged on, he was an ever more political artist, with apartheid and AIDS being issues that stocked his increasingly complex pictures with angels, demons, and two-legged snakes. (From Gooch we learn that Haring revered Hieronymus Bosch. No surprise—the freakish menagerie in The Garden of Earthly Delights is a plain ancestor of Haring’s mad doodle-verse.)

But his determination that art was for everybody also led him into outright merchandising, designing Swatch watches and Absolut Vodka labels, and opening the Pop Shop, a retail outlet in SoHo for Haring T-shirts, refrigerator magnets, and whatnot. To treat the cash register as just one more tool in the artist’s kit—this was something not even the money-mad Warhol had dared.

Haring would argue in his defense that, at a time when his gallery works could sell for tens of thousands, some items at his Pop Shop went for a dollar, letting anybody own “a Haring.” All the same, he was accused of selling out. To put it mildly, this was not a charge that Jeff Koons or, a few years later, Damien Hirst would care anything about, but it bothered Haring, who had a genuine sense of high mission.

Meanwhile, being a people’s artist didn’t mean flying coach. In his last years, on his many trips abroad, Haring was a regular on the Concorde. In Paris he stayed strictly at the Ritz, even if his sneakers got him barred from the hotel’s restaurants.

Late in 1988, in Tokyo, he discovered a thing he had long feared, a purple lesion on his leg from Kaposi’s sarcoma, the cancer that was a sure marker of AIDS. There followed about a year and a half of barely effective medications and hopeless home remedies but also a dazzling final burst of work. It included acrobatic steel sculptures, a 520-foot mural in Chicago made with the help of 300 public-school kids, and—by invitation—a multicolored tangle of figures on the exterior wall of a church in Pisa. He called it Tuttomondo—“all the world.”

That was, of course, a valedictory title, a wave good-bye. By 1990, as his energies dwindled, Haring was letting go of that world. He died on February 16 in his own bed, cradled on either side by his loving normie parents, who had long since come to terms with the meteor fate had dropped into their nest.

And then? Haring had worried that his Pop Shop kept American museums from taking him seriously. And it may have. During his lifetime, most held him at arm’s length, unsure whether he belonged in their galleries or just their gift shops.

But by the late 90s, even the Americans were coming around. The pulsing intricacy of his best work was just too compelling to deny, to say nothing of its affinities with the cartoonish art brut of Jean Dubuffet and the child-like spirit of Paul Klee and Alexander Calder. And to judge by the large traveling retrospective organized last year by the Broad museum, in Los Angeles, all is now forgiven.

Next stop, the Art Gallery of Ontario, in Toronto. After that, Minneapolis. Haring may be gone, but that radiant infant? Still going.

Richard Lacayo is the former art and architecture critic at Time. His most recent book is Last Light: How Six Great Artists Made Old Age a Time of Triumph