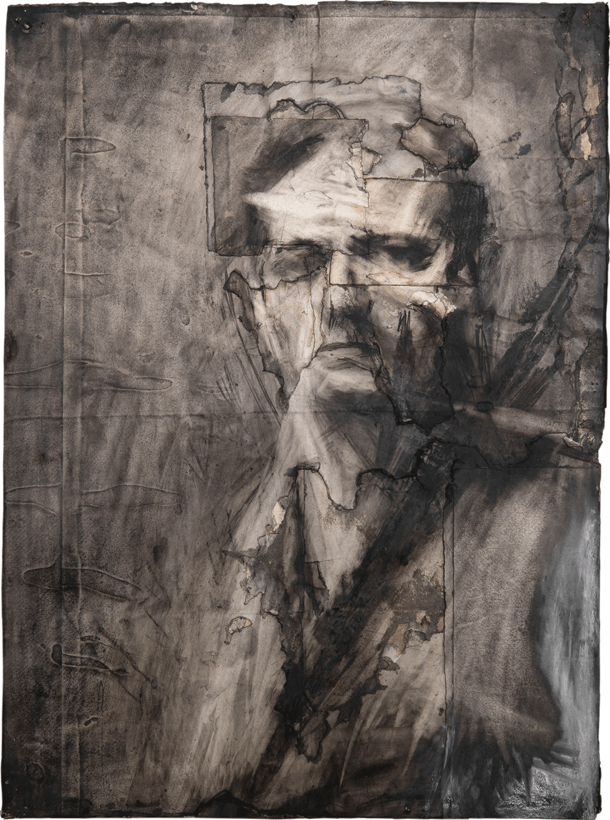

Frank Auerbach’s 1958 Self-Portrait confronts viewers with roughly treated paper that has been torn and patched, its repeated erasures and reworkings lending the artist’s visage a phantom yet piercing quality. The shape of the eyes, mouth, and nose are exquisitely rendered, but the face’s inscrutable gaze remains the artist’s secret. The portrait was created with charcoal, a Renaissance medium used for the underdrawings of paintings, and it is with charcoal that Auerbach pushed drawing beyond conventional limits.

Auerbach was in his late 20s when he made this self-portrait. He is now 92 and is still producing both paintings and drawings of uncommon verve. Yet never was his work quite so classically figurative as in the early charcoal portraits he completed between 1956 and 1962. Seventeen of these drawings, along with six paintings made during the same period with the same sitters, are the subject of “Frank Auerbach: The Charcoal Heads,” which goes on display next Friday at the Courtauld Gallery, in London.