Two weeks ago, Georgia’s ruling party, Georgian Dream, announced it would pause the nation’s accession talks with the European Union until at least 2028 and refuse all E.U. funding until then. The move, contradicting the Georgian constitution, which mandates the country work toward E.U. membership, led to resignations of government officials and sparked widespread demonstrations in the capital, Tbilisi.

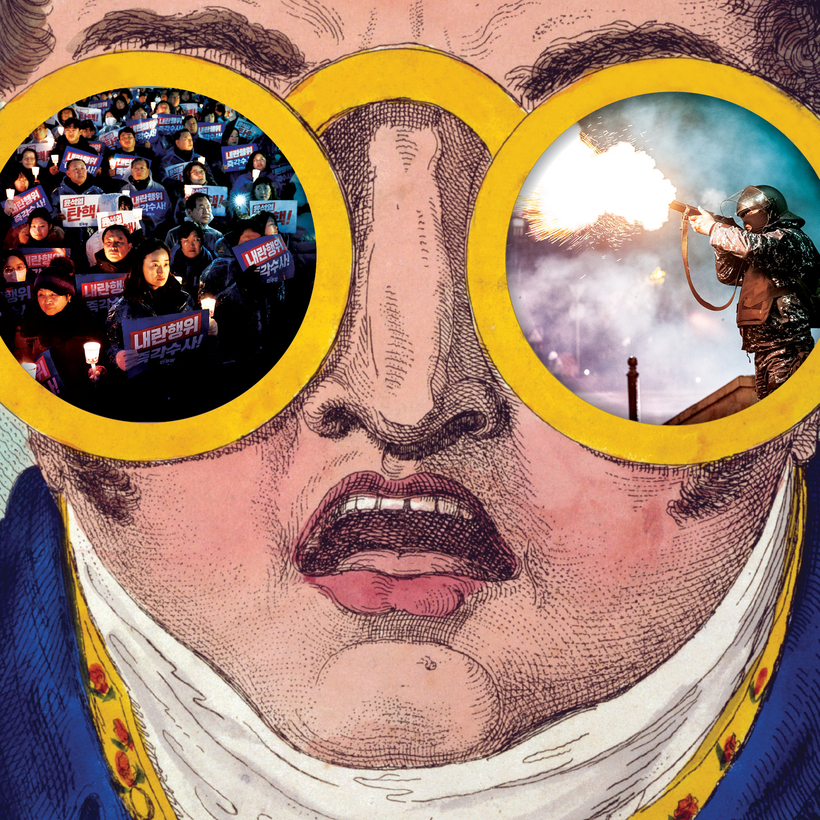

For several consecutive nights, thousands of people have been gathering outside the parliament building to protest what they see as a turn away from the West and toward Putin’s Russia. Every night, the protesters are beaten, tear-gassed, and, in the freezing Georgian winter, sprayed with cold water.