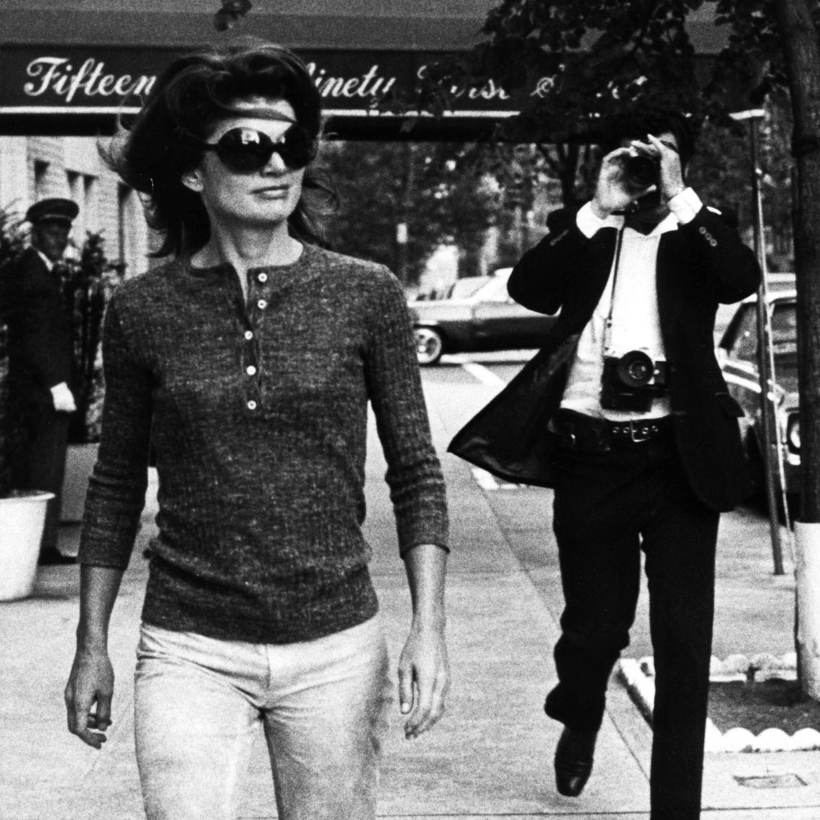

In many ways, the American media told Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’s story. Beyond her time as First Lady, and after she masterfully orchestrated John F. Kennedy’s funeral, in 1963, and then established Camelot as his legacy, she kept her thoughts largely to herself. A public figure, she very much believed she deserved an existence as a private person—even if others frequently trespassed upon that privacy.

But in 1972, in a lawsuit against the overzealous celebrity photographer Ron Galella, Onassis used her voice, and she used it forcefully. She argued for her right to move unencumbered in public spaces without threat or fear from the sustained harassment she and her children had experienced at the hands of Galella for years. Finding that voice in the historical record was a real gift to me when I was researching my book Our Jackie, and it connected her life more directly to the lives of women navigating public spaces—in 1972 and in the present day.