translated by Ekin Oklap

In his 2005 memoir, Istanbul, the Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk describes being more interested in the imaginary world as a child than in the real one. He’d daydream about a body double, also named Orhan, who lived “somewhere in the streets of Istanbul, in a house resembling ours …” Alone in his grandmother’s opulent living room in the afternoons, he’d look out through the window at the ships passing through the Bosporus and conceive of the room as the captain’s station of a giant ship that he was steering through a storm.

The first time he watched a movie—an adaptation of Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea—he was too little to read the subtitles, but he still made up a story of his own connecting the scenes. “Even later,” he wrote, “when I could read a book perfectly well, what mattered most was not to ‘understand’ it, but to supplement the meaning with the right fantasies.”

I thought of little Orhan while browsing through Memories of Distant Mountains, a selection of Pamuk’s illustrated journals. They roughly span the years following the publication of Istanbul, the decade and a half during which Pamuk catapulted into global fame after winning the Nobel Prize in Literature, in 2006. His reflections are punctuated by a novelist’s anxiety and utter self-absorption. “I am inside my novel,” one entry begins. Then, a few paragraphs later: “If I could just be alone with my novel, I’d be happy.” From time to time he records his nightmares, on other occasions his untrammeled feelings about his literary heroes: “Tolstoy is the greatest of all novelists.” “What Thoreau did for Walden, I am doing for Istanbul.”

We meet Pamuk in Istanbul, scrambling to set up the Museum of Innocence, an archive of mundane objects reminiscent of midcentury Turkey—from women’s scarves to lipstick-stained cigarettes—that appear in his novel of the same name. A few pages later, he is at the Jaipur Literature Festival, sharing a meal with the novelist (and fellow Nobel laureate) J. M. Coetzee.

In New York, when he isn’t fussing over the readings he has assigned to his students—he teaches at Columbia University every fall—he is plugging away at a novel in the Avery Library or staring at landscape paintings inside the Met. In Venice, he is impressed by the Turkish pavilion at the 2009 Biennale. In France, we run into him “listening to Mozart on the train to Lyon, thinking and daydreaming.” In Greece, he waxes eloquent about the pleasures of swimming in the Aegean Sea after sundown.

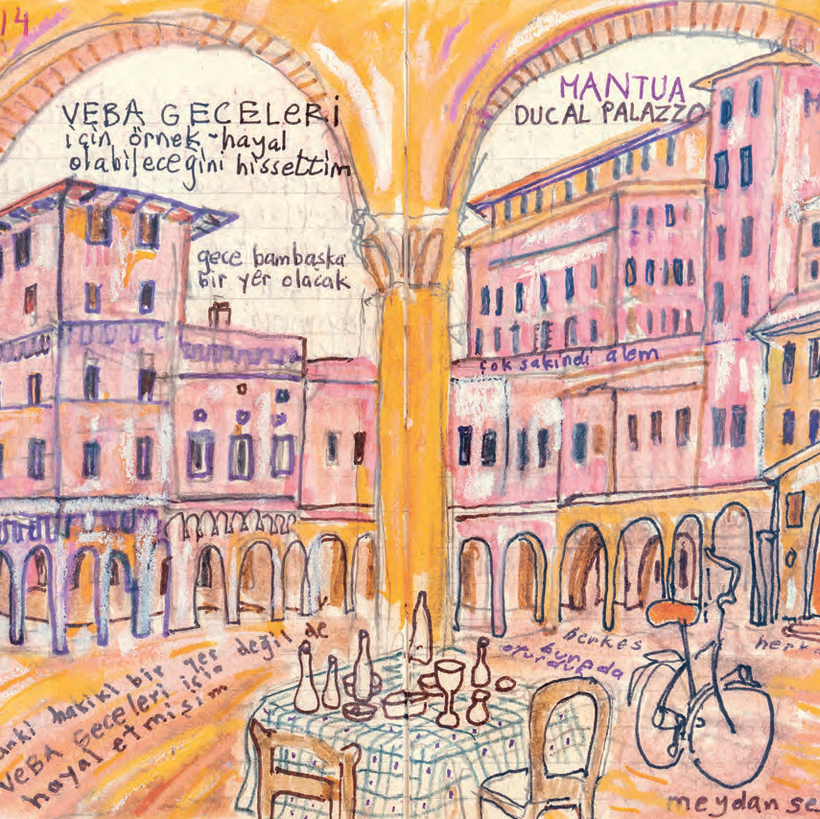

What rescues these diary entries from being just the cathartic musings of a jet-setting celebrity author are the paintings that inscribe every page. Pamuk’s process, as he reveals in the opening pages, was to conceive of images and words in chorus: “On some pages, the text came first, and for months, sometimes years, afterward, I didn’t draw anything on them.... Some days I would be inspired to make a drawing and nothing else. The text would come later.”

A typical page might include an ekphrastic poem overlaid on top of a roadside scenery somewhere in Greece, or a scattering of Turkish words tumbling down like rain over a dismal view of hills. Readers of Istanbul will recall that Pamuk painted top-down landscapes all through his formative years in the city, before deciding to become a writer at 22. These drawings mark in many ways an imaginative return to childhood, “the familiar, happy place I used to know.”

In Istanbul, Pamuk employed the Turkish word hüzün to sum up the sense of communal desolation in a city where “the remains of a glorious past and civilization are everywhere visible.” In these entries, the city is mostly glimpsed through a window from the safety of Pamuk’s office or living room, and neighborhoods are remembered for what they used to be.

Pamuk has had bodyguards for two decades now, ever since Turkish nationalists took issue with his comments about the 1915 mass killings of Armenians and Kurds. In 2021, he was accused of insulting the founder of modern Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, and ridiculing the Turkish flag in his novel Nights of Plague.

Ever since the strongman Recep Erdoğan ascended to power in Turkey, Pamuk has cut a lonelier and more careful figure, unable to move around his native city at will. Sometime in 2019, his wife, Aslı Akyavaş, implored him not to “publish anything too personal.” Pamuk records the moment in these journals early on, as if to encourage us to read between the lines.

Gaps and silences are everywhere in Memories of Distant Mountains, whose contents, Pamuk writes, are “not in chronological but in emotional order.” You admire a landscape now and again but can’t make head or tail of the chunk of accompanying text: much like little Orhan, you’re supposed to supplement the meaning with your own fantasies. One moment Pamuk is driving around Goa with his ex-girlfriend the Indian-American novelist Kiran Desai. A couple of pages on, he is glancing longingly at Akyavaş from his desk in Istanbul.

The book lacks a robust narrative tissue, the self-incriminating bits that make reading someone else’s diary invariably riveting. The late critic Gary Indiana once wrote that “we all live at least one or two lives that we subtract from biographies.”

At 72, Pamuk has chosen to subtract precisely these secret lives, the moments of vulnerability and awkwardness that one would rather not dwell on for too long. Fifty years after he decided to pursue a career as a novelist, Pamuk has become a writer who hesitates to bare himself on a page.

Abhrajyoti Chakraborty is a New Delhi–based writer and critic