Last week, Dulwich Picture Gallery opened a door into the enchanted world of Tirzah Garwood. Art circles gently buzzed in anticipation, asking, “Who is Tirzah Garwood?” A surrealist perhaps, with a small s? Did her love of Victorian and Edwardian children’s-book illustration influence her play on scale, a conviction held by the show’s curator, James Russell? Was she a proto-feminist? Some of her work looks like a moment in time from an uncanny fairy tale.

It’s not that people don’t know who she was. Tirzah Garwood has always existed on an anecdotal level. She was a talented artist who happened to be Eric Ravilious’s wife, and sometimes the subject of her renowned husband’s watercolors and prints. People have an idea of what she looked like. And there have been rare magical glimpses of her work. In 2010, an untitled small embroidery was shown at “Women of Great Bardfield,” at the Fry Art Gallery, in Saffron Walden, featuring a woman with a watering can in an idealized garden, so spellbindingly beautiful that once it has been seen it cannot be forgotten.

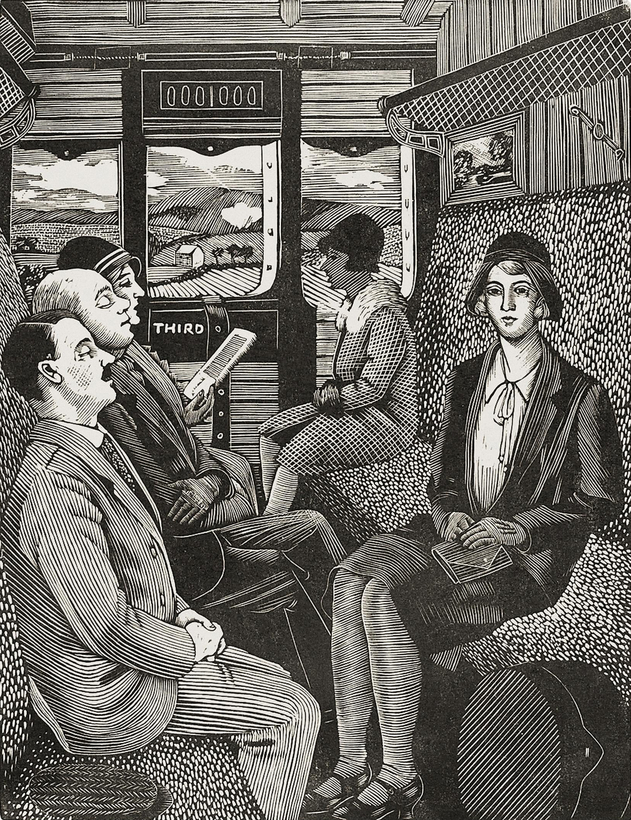

But this is the first time we get to see the whole picture, a coming together of 80 works in the mediums of oil on canvas, woodblock print, embroidery, paper marbling, house-portrait illustration, scrapbooks, and patchwork.

It is hoped that this exhibition will invite a new critical appraisal. No longer restricted by the artistic, social, and gender hierarchies of the day, or by Garwood’s own modesty, her art couldn’t have a better moment for re-emergence. Will the Dulwich exhibition move her narrative from that of wife then war widow to that of artist in her own right?

Tirzah, born Eileen Garwood in 1908, was head girl at school and Lieutenant Colonel Garwood’s daughter when she met Ravilious in a woodblock class he was teaching. Seventeen years old, she was his star student. Romance did not blossom immediately; it took a broken engagement (hers) and four years of friendship before the two finally married, in 1930. The bright young couple bridged their social differences with a passionate belief in art, and lived an artisanal life in London and then Great Bardfield. Ravilious became a successful watercolorist and painter of murals, and his wife helped him. She later became expert at marbling papers, a supplement to their income as children came, and was always productive.

Tragedy struck in 1941. Garwood, by then a mother of three small children, was diagnosed with breast cancer and underwent brutal surgery during the hardest winter of the war. The following September, Ravilious, who was working as a war artist, went missing in Iceland. His impoverished widow grieved painfully for the family life that was lost, and the stoicism she showed—that Battle of Britain spirit, so astonishing to modern eyes—can only be understood in the context of another time.

Relative stability returned in the form of Henry Swanzy, a radio producer for the BBC who became Garwood’s second husband, in 1946. She began to paint in oil, and three precious pictures from this time—sophisticated yet searching—are in the exhibition: Horses and Trains (1944), Etna (1944), and The Old Soldier (1947). These immaculate compositions reflect the emotional restraint of the era. They are also disturbing, child-like compositions riddled with double meaning and sorrow.

Garwood was producing on many levels, adding house portraits, children’s illustrations, and Victorian-style scrapbooks to her practice. In 1948, however, cancer returned. She would die in 1951, at 42. In her final year, which she described as her happiest, Garwood produced 20 canvases imbued with a strangeness that quietly subverts their seeming domesticity.

“Tirzah Garwood: Beyond Ravilious” is on at Dulwich Picture Gallery, in London, until May 26, 2025

Sarah Hyde is a London-based writer