Nobody who ever met Oliver Hoare could be objective about him, and I, who had the good fortune to know him, will not even try: he was among the most charming, beguiling, handsome men I ever met. And the stories—my God!—those stories. You could be sitting at his table in Provence, plied with Burgundy after admirable Burgundy, and Oliver’s dark eyes would begin to gleam with the lingering promise of there hangs a tale …

Then, from the lips of one of the legendary Islamic-art dealers of the last century, who happened also to be roommates with Bruce Chatwin, such stories as ought to belong in a modern Arabian Nights would pour out: involving motorboats racing down the Bosporus from which smuggled medieval Korans were thrown overboard, opium-laden orgies in caravanserais in pre-revolutionary Iran, and mornings of white heat, in which Princess Ashraf, the sister of the last Shah, or the Shahbanu herself, made casual appearances.

To a twentysomething, who was friends with his son Tristan, Oliver represented something very special about Britain itself as the country of the dazzling amateur. I was about to embark on a journey across the Islamic world, which would give me the material for my first book, Stranger to History. Oliver was a North Star of sorts. Here was the son of a vodka-drinking Sufi and British spy, who through charm and good looks broke into the highest echelons of Iranian society, but then, through sustained passion and study, also went on to become one of the world’s leading experts on Islamic art, establishing at Christie’s (where he worked from 1967 to 1975) the very first Islamic-art department at a major auction house.

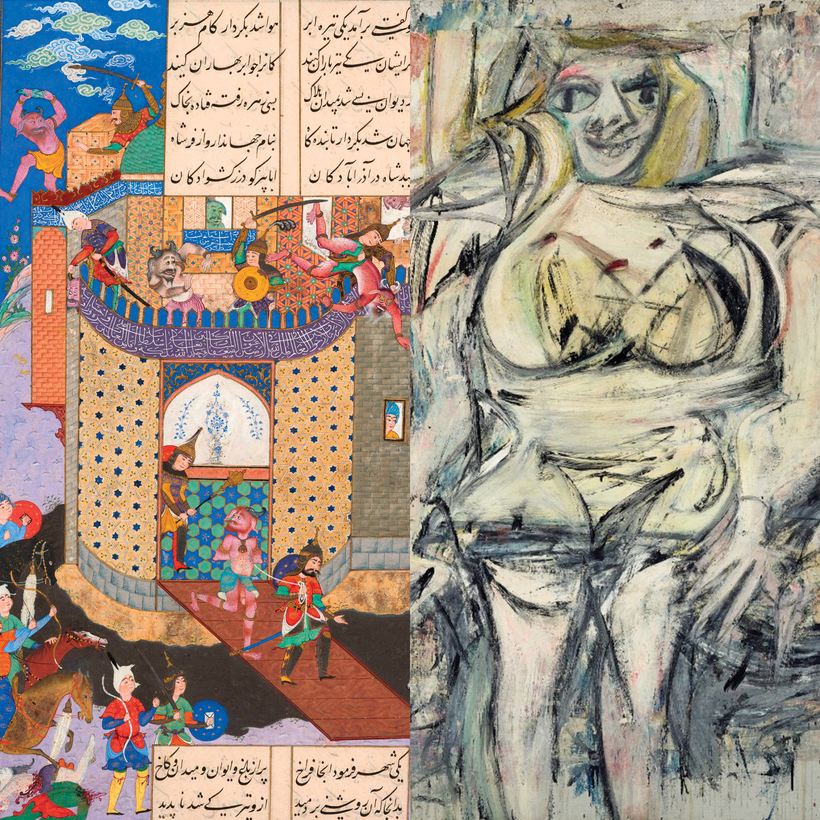

Oliver died in 2018, and in his posthumously published book, The Exchange: Shahnameh/de Kooning, which he was at work on till his death, he tells us the story of his greatest caper: how in 1993 he effected a secret exchange between what had become the Islamic Republic of Iran and Arthur Houghton II, an American bibliophile who owned one of the finest manuscripts ever produced of Iran’s national epic, the 16th-century Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp, trading its exquisite pages for a painting that affronted the sensibilities of the prudish theocracy, namely Willem de Kooning’s Woman III.

The latter had been collected by the Shahbanu for her Museum of Contemporary Art and had been sitting in a vault, too racy to be displayed, until Hossein Moini, an Iranian living in California, who was in possession of a list drawn up by the Iranian government of works of art in the West that they wanted most to recover, suggested the idea of the exchange to avoid charges of corruption. It would involve two steps: first, the exchange between Houghton and the Islamic Republic, which would repatriate the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp after 424 years in exile; then a third-party sale of the de Kooning to compensate Houghton.

Here was the son of a vodka-drinking Sufi and British spy, who through charm and good looks broke into the highest echelons of Iranian society.

What begins as a memoir in crisp Chatwin-esque prose of a world now lost to us—Oliver leaving the Key Club in Tehran at three a.m. for Chekhovian country estates, dotted with plane trees and poplars, where bottles of white wine are cooled in nearby streams—turns into an Argo-like thriller of letters traded back and forth between Hoare and the Islamic Republic, of shadowy middlemen and secret trips to Tehran. The final will-it-or-won’t-it-happen moment takes place on a tarmac in Vienna, with Oliver in possession of both the crated folios of the great manuscript and the painting, which David Geffen (the secret buyer) would sell on to Steven A. Cohen in 2006 for $137.5 million.

What I loved about The Exchange was its idiosyncrasy and its voice. It is knowing in a way few books are these days. In Oliver’s descriptions of Iran’s elite as clubbish, gossipy, deracinated, one is given an extremely vivid portrait of a country on the precipice of revolution.

One of the characters, Hamoush Azodi, through whom Oliver is introduced to Tehran society, is someone I used to know when I lived in London in the 2000s. I remember her in a black lace dress with a ruff that went right up to her chin. She had a cap of dyed, woolly black hair and was heavily made up, blue eye shadow and lipstick against a moisturized face. Of Hamoush’s family, Princess Michael of Kent used to say, apocryphally, no doubt, “They owned the rain that fell on their land, and they taxed the peasants on the rain, so you can see why there was a revolution, my darling.”

In country after country today (not least our own), one lives in the knowledge that the old order is fading away, even as the thing replacing it may not be any better. It is the quiet melancholy of this realization that suffuses The Exchange. It mourns a vanished age (“Later in the evening the manghal would arrive—a brazier full of glowing charcoal—with a servant to prepare the opium pipes”) while looking squarely at the reasons for its demise. And, like Oliver himself, speaking from beyond the grave, it is wonderfully entertaining in the bargain.

Aatish Taseer is the author of many books, including The Twice-Born: Life and Death on the Ganges. His forthcoming collection, A Return to Self: Excursions in Exile, will be published in 2025 by Catapult