When the curtain comes up on Mark Rosenblatt’s superb debut play, Giant (commandingly directed by Nicholas Hytner at London’s Royal Court Theatre), Roald Dahl, the six-foot-six giant in question, is hunched approvingly over the galleys of his latest children’s book, The Witches, working on changes to Quentin Blake’s drawings. “Much nastier. Blistering scalps, clawed fingers, good. And her in the middle. Relishing the bloodlust to come,” he says to his oleaginous British publisher in the play’s first beats. That turns out to be Rosenblatt’s game plan, too. He is telling a tale of bloodlust and monstrousness of a different kind.

The word “monster” has its roots in the Latin for “blessing” and “warning.” The blessing of Dahl’s storytelling genius is transparent in his 48 books, which have sold around 300 million copies worldwide, and the rights to which were bought by Netflix for a reported $1 billion. The warning is in Dahl’s unabashed anti-Semitism, which emerged in a 1983 interview with The New Statesman, as he defended his anti-Israeli statements in a previously published book review. This scandalous event, which hit the newsstands just as The Witches was about to go to press, is the play’s inciting incident.

Rosenblatt invents a thrilling Mexican standoff between Dahl’s English and American publishers, both Jewish, as they try to keep their dyspeptic author’s reputation and their profits from going down the plughole. (Dahl died unrepentant in 1990; the Dahl estate apologized for his anti-Semitic utterances in 2020). The blood-boiling stakes couldn’t be higher. Dahl, like his fictional witches, is “dangerous because he doesn’t look dangerous.” He boxes clever, by turns charming, quick-witted, lacerating, ironic, sadistic.

Into his fictional argument Rosenblatt deftly weaves Dahl’s actual, scurrilous public statements, which are as indigestible as they are impossible to massage. “There is a trait in the Jewish character that does provoke animosity, maybe it’s a kind of lack of generosity towards non-Jews,” Dahl told The New Statesman. “I mean there’s always a reason why anti-anything crops up anywhere; even a stinker like Hitler didn’t just pick on them for no reason.”

Here, the shards of argument are based on Dahl’s animosity to the 1982 Israel-Lebanon war, which mirrors directly, almost exactly, the outrage and divisive rhetoric of the current Israel-Hamas conflict. Rosenblatt’s interest is not in special pleading for one side or the other—all parties are right, wrong, intractable. The production’s particular nuanced achievement is to define the landscape of bigotry where violence makes thought impossible.

The immanence of Dahl’s deracination is embodied in Bob Crowley’s cunning, discombobulated set—a large, stripped-out living space undergoing noisy renovation, a world turned upside down, where Dahl is starting a new life with the much younger Liccy Crosland, his mistress of 11 years. Clamps prop up the ceiling joists, and a huge plastic sheet covers the back wall so the outside world is unseen but permeable. Except for a few incidental pieces of furniture, the place is a frenetic, uncomfortable, punishing vacancy. “Apocalyptic” is Dahl’s word for it.

Pain is the play’s subtext. When Dahl is onstage, according to the directions, “he moves through a cacophony of pain.” The set is the first to inflict it. The builders’ pounding causes Dahl to flinch. “It’s like their scaling my fucking spine … little demons with little ice picks,” Dahl bristles. “Whatever is ill at ease in you—let’s banish it.... Focus on your life here with me. With me, and not these sapping frustrations,” his wife-to-be counsels. Dahl’s excruciating pain—he perpetually rubs his back, props himself up gingerly from chairs, winces, stretches—may account for his irascibility but not for the mystery of his acid racist thought, which is a demonstration of something deeper.

Dahl is permanently braced, a residue of repressed fury, which on the page turns loss into fun but in life turns him into a dervish of disdain. “Squish them and squash them and make them disappear” is the sadistic motto of the witches in his book. The same spirit of annihilation marks his spiky negotiations with his publishers. They want some conciliatory public statement; he will concede nothing. They’re broadcasting, but he’s not receiving. By objectifying the anxious executives with dismissive epithets, he puts them and their arguments out of mind. Tom Maschler, of Jonathan Cape (the smooth Elliot Levey), is “a house Jew”; Jessie Stone, the representative of Farrar, Straus and Giroux (Romola Garai, on eloquent good form), is variously a “desk monkey,” “the dragon,” “a human booby trap.”

He boxes clever, by turns charming, quick-witted, lacerating, ironic, sadistic.

Dahl lampoons the imbroglio, going so far as to drag into the fracas his pert, young New Zealander cook, Hallie (the droll Tessa Bonham Jones). “Would you buy an Israeli avocado?.... Or would refusing to buy it be anti-semitic?,” he says. “Does the avocado know it’s Israeli?” she says, adding, “Someone’s got to stand with the avocado.” The retort gets a huge laugh from the audience but not from Dahl, who is knocked off his toxic game for the first and only time.

As Dahl goes toe-to-toe with his Jewish publishers, Rosenblatt hints with the deftest of light touches at the world of woe that is his backstory. In a sense, Dahl’s unrelenting sarcasm and send-ups are a performance of suffering beyond words. He puts into others the indigestible torment of his own losses. “No one else understands. Like stepping into a new world, over a line you didn’t know existed,” he says in a telling, throwaway observation about one of his great griefs.

At three, Dahl lost his father and eldest sister; at seven, he was sent off to English public school, “days of horror” he recalls in his autobiographical Boy. Horror found him again in adulthood. He lost a young daughter to measles; his son was brain-damaged when his pram was hit by a taxi; he nursed his first wife of 30 years, the actress Patricia Neal, back to health after three strokes left her for a long time unable to speak or walk.

Part of Dahl’s unexamined animus against the Jews, the play seems to suggest, is their sanctimony, which, because of the Holocaust, puts them in the avant-garde of suffering. “Your righteous anger, your ancient wounds you hawk like cheap linen, they don’t make you wiser—they give you partial sight,” he tells Stone, Rosenblatt’s invention, who serves his drama as a Zionist flamethrower. Dahl goes on: “You sit here in my house, as my publishers, insisting I bow to a public clamor, utterly blind to how despicably racist you are.”

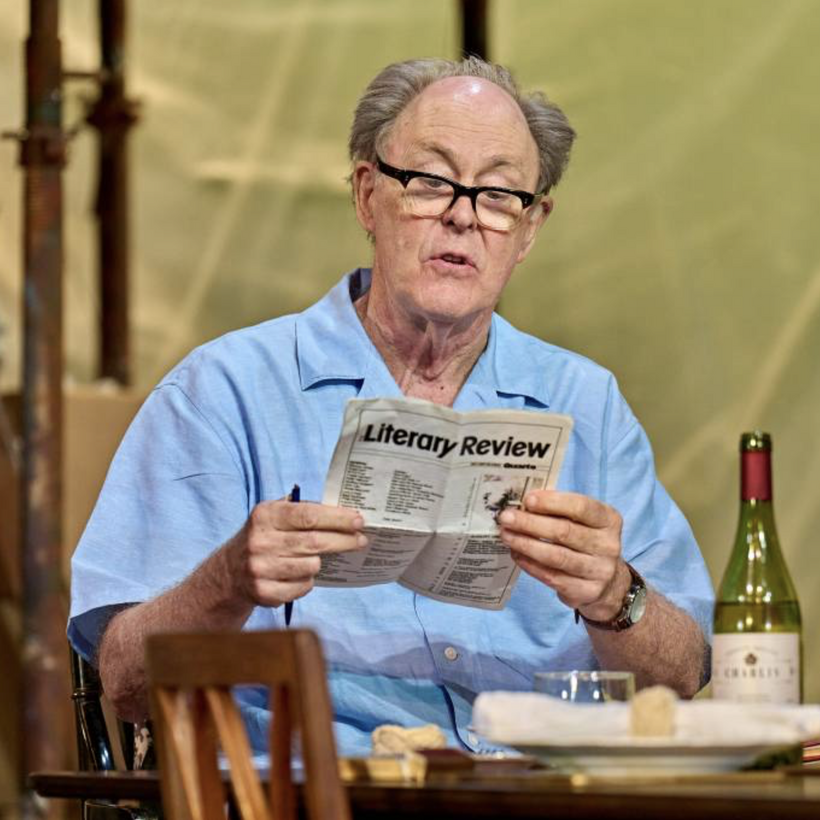

As Dahl, the lanky, lean John Lithgow gives one of the finest performances of his distinguished career. The English would say he “plays a blinder”; the Americans would say he’s “showstopping.” Whatever words you want to throw at Lithgow’s articulate energy, it’s a master class in acting. Lithgow exudes a warm, alert intelligence. He’s swift. He shares with Dahl a natural patrician charm and wit. He rings all the variety of vindictive mischief out of Rosenblatt’s juicy dialogue. “The eaglet has landed,” he says when Stone arrives late for the powwow.

Later, trying to impress Dahl with her bona fides as a progressive Jew, she admits to being “able to see Israel’s mistakes and flaws.” An opinion, Dahl says, which reminds him of his old friend Colin. “I can see all his foibles…. Colin is my Israel, I suppose. Always punching people and blaming the barman,” he says, smiling with cold teeth.

Stone’s outbursts make her more or less persona non grata in Dahl’s home, but not before she calls him out. “You want me in anguish, Mr. Dahl. Because you’re a belligerent, nasty child. And these threats and cruelties, a child’s. It’s the gift of your work, and the curse of your life,” she says. Dahl is a swine, but it’s not Rosenblatt’s goal to expose him as much as it is to reveal bigotry’s refusal to think. He doesn’t offer any easy answers or a last-minute reprieve from the bargain basement of melodrama. Dahl stands his ground and doubles down on his slander. To see brilliance you need shadow; here, in this exemplary production, it’s the shadow that’s dazzling.

The exhilaration of Giant goes way beyond its complex character study. In the din of the current, catastrophic Middle Eastern impasse, where it’s so hard to hear the other, Giant’s achievement is to do art’s job of giving words to suffering and making us hear them.

John Lahr is a Columnist at AIR MAIL and the first critic to win a Tony Award, for co-authoring Elaine Stritch at Liberty