My introduction to Abercrombie & Fitch came through LFO’s “Summer Girls,” the 1999 song best remembered for name-checking the brand multiple times. I remember asking my mom what Abercrombie & Fitch was, because I had never even heard of it. Growing up in the small city of Hazleton, Pennsylvania, it wasn’t something that had infiltrated my high school—yet. I also remember when, some time after, the first Abercrombie store opened within driving distance, and I just so happened to stumble upon the store’s trainees, the young workers who would embody the Abercrombie & Fitch lifestyle at the store in Scranton.

More than two decades later, Abercrombie & Fitch has productively shed that well-curated image—the one of “natural”-feeling, fit, good-looking young people in ripped jeans, fitted polos, and flip-flops—for something that resonates more today. Yet, as an elder millennial, those images of the “Abercrombie teens” remain lodged in my head. And what struck me in researching my book The Abercrombie Age: Millennial Aspiration and the Promise of Consumer Culture was just how widespread the tenets of the Abercrombie & Fitch brand were throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s.

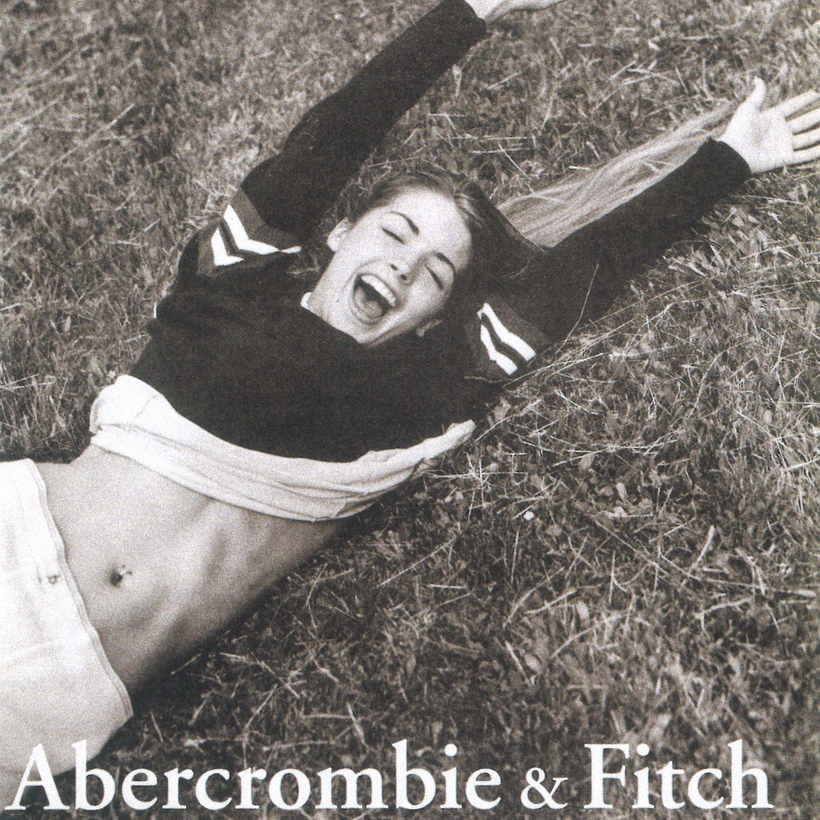

For anyone not traumatized by the Abercrombie & Fitch of the era, let me recap: the store was widely known for a club-like, cologne-blasting atmosphere; advertising filled with naked coeds and ripped abs; and exclusionary hiring policies that put the “cool kids” front and center while moving others who didn’t fit the image, including people of color, to the stockroom or off-peak hours. (The Netflix documentary White Hot does a good job of explaining the multitude of problems during Abercrombie’s heyday.)

Nevertheless, the advertising ran deep—not only did “Abercrombie” become lingo for a certain type of teen, but the brand’s images of carefree young people living it up in school and on sun-kissed beaches merged seamlessly with the rest of popular culture.

Films such as She’s All That and 10 Things I Hate About You, the TV show Dawson’s Creek, and the music videos of Britney Spears and Christina Aguilera shared in this same imagery of idealized teenagedom: pretty, thin, (mostly) white, and (mostly) well-off teens living their best lives. School lunches on an open-air quad, jumping house parties, and extravagant school dances were par for the course. The messaging was repeated so often that it became an insidious refrain: this is what you could—and should—be doing. And if you weren’t living your best life, you were just a shopping trip and quick makeover away from achieving everything you could ever want!

Looking back at these idyllic images presented to teens of the time, it’s no wonder that Abercrombie & Fitch and similar retailers were able to help brand, package, and sell the concepts of the perfect high-school experience. As Abercrombie’s C.E.O. at the time said, they were selling to the cool kids, but who wouldn’t want to buy into that privilege? Yes, I wanted to eat outside under the sun rather than inside a crowded cafeteria, and, yes, I would have preferred hanging out at the beach rather than go to my after-school job at the local Walmart.

The eternal optimism of consumer culture wasn’t limited to millennials’ high-school years, either—movies like The Skulls and Legally Blonde helped sell us on the “right” types of colleges to go to, while Sweet Home Alabama, The Devil Wears Prada, and Employee of the Month divided the worthwhile careers from the embarrassing ones. Life could—and would!—get better if we toed the line, followed the rules, bought the right things.

Of course, this unfettered belief in consumer culture was always a fiction—a credit card and a sense of style would never be able to propel people upward in the face of wage stagnation and increasing wealth disparities. For its part, Abercrombie & Fitch lost its “cool” factor—and the C.E.O. who promoted its exclusionary ethos lost his job in 2014. As the store turned up its lights, the images were exposed as little more than a mirage; it was just the repetition of these messages in popular culture that led us to believe the Abercrombie lifestyle ever existed and that we might achieve it.

Myles Ethan Lascity is a Dallas-based writer and professor