Frank DiGiacomo

The week I started reading Paper of Wreckage, Eric Adams became the first New York City mayor to be indicted while in office, under a whopping and frequently comical list of alleged bribes and favors from the government of Turkey, along with accusations of bilking the campaign-finance system out of millions of dollars. The front page of the next day’s New York Post read, “I AM A TARGET,” quoting Adams’s complaint that the charges were, as the subhead put it, “payback for complaining about Biden’s migrant crisis.”

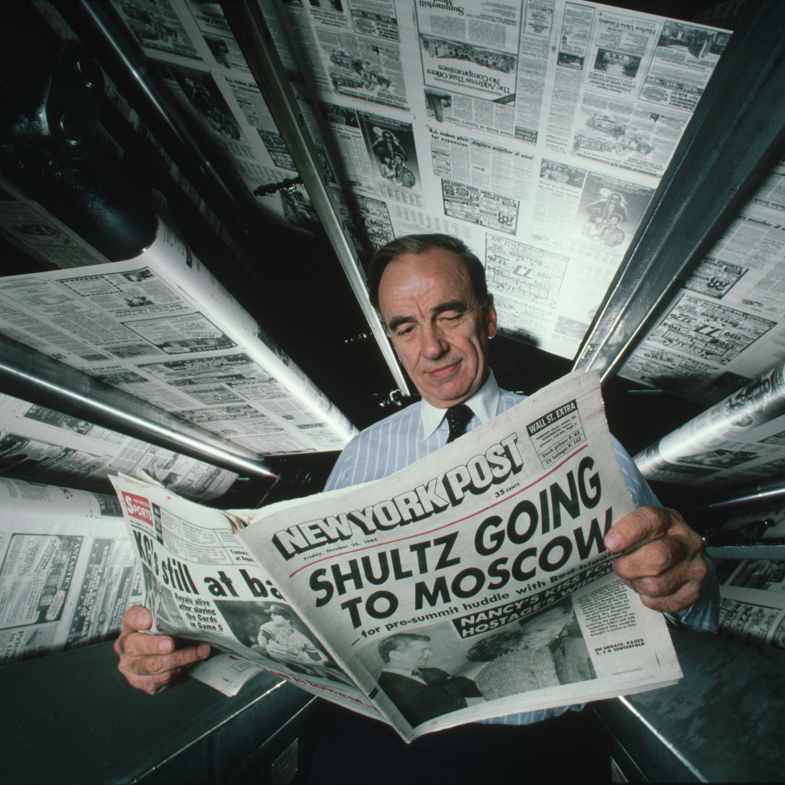

Why was the Post filling page one with a tepid defense of the mayor, featuring a talking point from Donald Trump’s presidential campaign? Early in Paper of Wreckage, Eric Fettmann, a former columnist and editorials editor for the Post, tells the authors, Susan Mulcahy and Frank DiGiacomo, that after the citywide blackout of July 1977, Mayor Abe Beame blamed the Post’s 24 HOURS OF TERROR front page for ending his political career. Further on, Wayne Darwen, a managing editor from the 80s, describes the paper’s editorial ethos as he understood it: