When I was 12, Jim Morrison lit my fire. I could not put down Jerry Hopkins and Danny Sugarman’s biography, No One Here Gets Out Alive (1980), which I hid in my textbooks like a fake ID. The Lizard King was, I learned, a poet, a satyr, a drunk, a mystic, who sang things such as “There’s a killer on the road / His brain is squirmin’ like a toad.”

Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen wrote way better lyrics, but they did not wear leather pants, get arrested, or pose shirtless. Morrison advertised a sexy anarchy, although this had its downside. According to No One Here Gets Out Alive and Oliver Stone’s biopic The Doors (1991), this rock god, a healthy man in his mid-20s, needed to be dangled outside a hotel window for functional coitus. Reading this in my bar mitzvah year, I learned to be careful of what I wished for.

If being a rock star is a kind of poetry, Jim Morrison was Dionysus and Icarus rolled into one. Plus, leather pants. I knew that after six albums, six arrests, and a conviction for indecent exposure, Morrison broke on through and joined the infamous “27 club” in 1971. (Or did he? The biography had enough conspiracy theories for Alex Jones.)

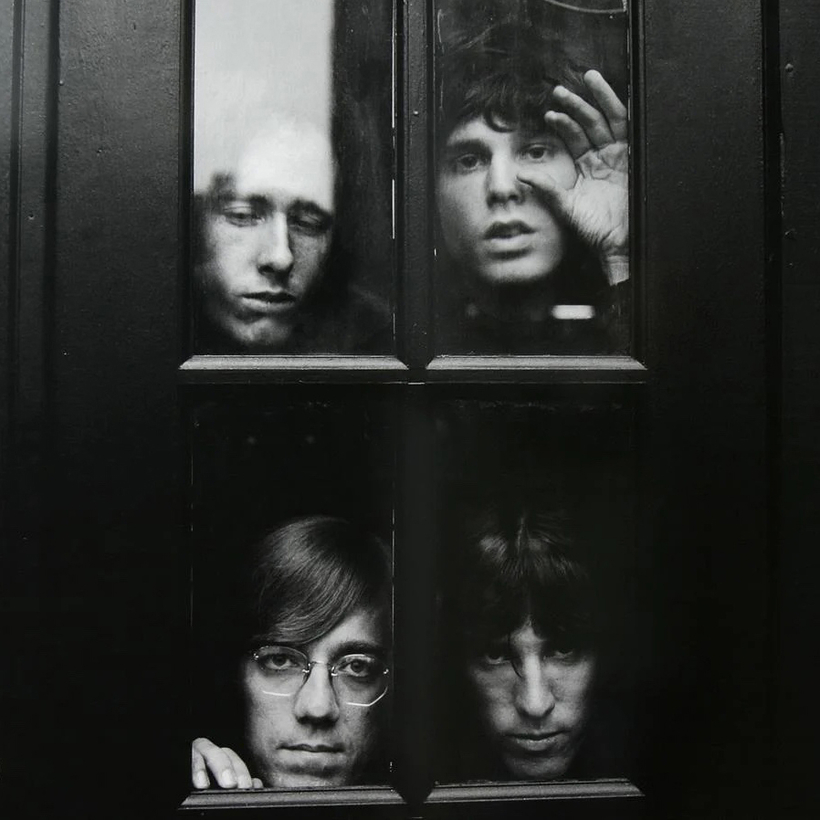

I later learned that the book was the industry standard for rock biographies. I didn’t think much about what became of the surviving Doors—Robby Krieger on guitar and Ray Manzarek on keyboard—except that they must have been rolling in it. Their music was getting played every day on classic-rock radio. The catalogue is now worth more than $10 million in annual revenue, and that doesn’t even count the eye-popping offers for reunion tours and licensing. Rolling Stone put Morrison on the cover, writing: “He’s hot, he’s sexy and he’s dead.” The offers kept coming: $1.5 million from Apple; another $1.5 million from Pixar.

Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen wrote way better lyrics, but they did not get arrested or pose shirtless.

And this is where the trouble begins. The Doors had a “one for all, all for one” policy. Even though Morrison wrote all the lyrics and did all the singing, everyone got 25 percent, a potentially lopsided advantage for the other guys. (Morrison was not much of a planner, obviously.)

In an event dramatized in Stone’s film, when Morrison, played by Val Kilmer, discovers the use of “Light My Fire” in a Buick ad, he tries to throw the TV at Manzarek and tells his bandmates that they just sent a message to the world: the Doors are not real. (Manzarek disputed this account, but in his memoir, he recalled Morrison accusing his bandmates of having “made a pact with the devil.” As retaliation, Morrison threatened to smash Buicks at concerts.) In 1968, selling out was still a thing. A line was drawn, and while Morrison would (possibly) unzip his fly in front of a concert audience, he had his standards.

Doors drummer John Densmore now has an addendum to the band’s story, one that is decorated with blurbs from the likes of Tom Waits and Randy Newman, neither known for their effusiveness. They may not be fans of the Doors, but they are fans of Densmore for the story he tells in The Doors Unhinged: Jim Morrison’s Legacy Goes on Trial.

These guys entered adulthood sitting on a lotto ticket; Manzarek, the oldest, was 32 when Morrison died. They could live large based on intellectual property created when they were young, mostly thanks to the lyrics, singing, and notoriety of a single charismatic figure who left quite a money trail. All they had to do was sit around their fancy homes and let it rain. They could pick up projects and do lucrative nostalgia shows if they wanted, but without lifting a finger, the afterlife of this Jim Morrison character kept them in the 1 percent.

If being a rock star is a kind of poetry, Jim Morrison was Dionysus and Icarus rolled into one. Plus, leather pants.

And yet a deal is a deal. Morrison made it clear how he felt about the Buick ad, and honoring the wishes of the dead should be pretty basic, especially if you are an ex-Door who has profited so handsomely from all things Jim Morrison. In 2000, the ante was raised when Cadillac offered $15 million for licensing for an ad, and Densmore put his foot down. Manzarek was all for it, Krieger was in the middle, and Densmore took a stand.

While they were at it, Densmore wanted Manzarek and Krieger—raking in at least $150,000 a night on the nostalgia circuit—to stop billing themselves as the Doors, with the recognizable Elektra Records design-department logo. Manzarek and Krieger countersued for—get this—$40 million. Most of the book is a transcript of the trial, where you can hear all those royalties clinking into the lawyers’ pockets. Densmore wanted to give 10 percent of everything to charity, contribute anti-corporate articles to The Nation and The Guardian, and not sell out his dead friend. The others were almost all business.

In the end, my friend, on July 21, 2005, the court found Manzarek and Krieger guilty of false advertising. They had to cease and desist from calling themselves the Doors.

These guys entered adulthood sitting on a lotto ticket. They could live large based on intellectual property created when they were young, mostly thanks to the lyrics, singing, and notoriety of a single charismatic figure.

When they were first becoming well known, Morrison claimed his parents were dead. They weren’t, but they were dead to him. And yet his father, an admiral who was present for the Gulf of Tonkin, was there to be an ally to this aging hippie, who still wanted to believe he could keep the spirit of the 60s alive. He, a member of Morrison’s estate, believed his enfant terrible had integrity, in his way. One of Morrison’s songs, “The End,” had a monologue about patricide and incest, and yet, there he was, standing up for sonny boy.

“If the doors of perception were cleansed,” wrote William Blake, “every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite.” There is a lot of cleansing to litigate in Densmore’s book. The revolution never happened. Income inequality continues to worsen, but a few aging hippies made a sweet nest egg. Manzarek died a little over 10 years ago, but the empire lives on. Densmore litigated something that keeps receding into the past, but the offers will proliferate. This is the end, beautiful friend. Fat chance.

David Yaffe is a professor of humanities at Syracuse University. He writes about music and is the author, most recently, of Reckless Daughter: A Portrait of Joni Mitchell. You can read his Substack here