Once or twice a year, when I was a teenager, my father would take me into Manhattan for lunch with a group he belonged to, the Dutch Treat Club. On one of those occasions, in 1967, he made a point of introducing me to another of the members, a tall, thin man whose pinstripe suit and pencil mustache marked him as a visitor from a vanished world.

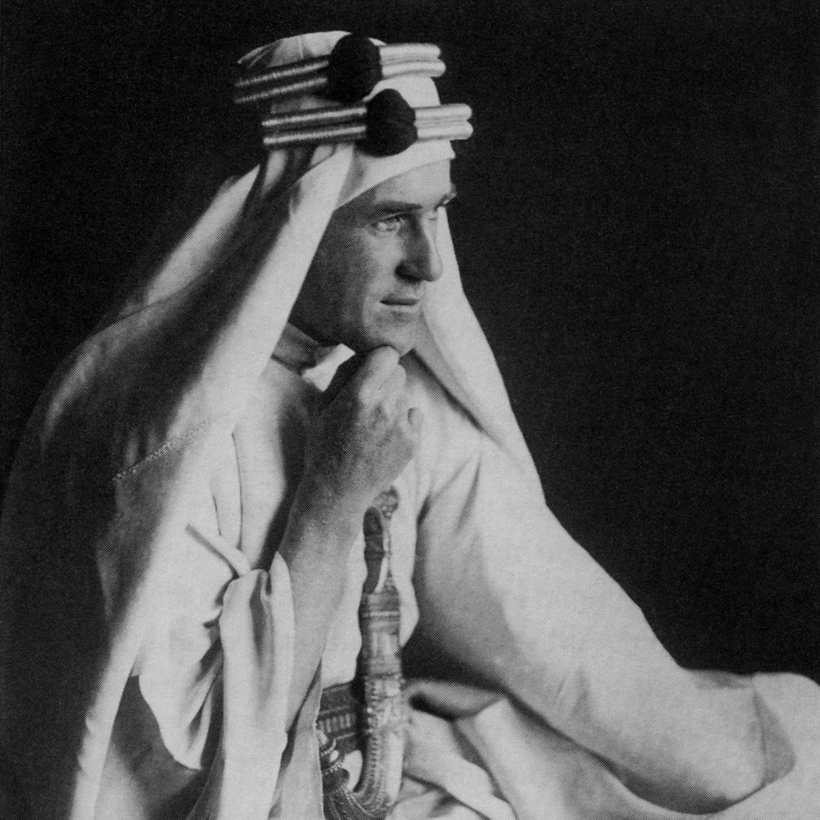

The man was Lowell Thomas, once among the most famous broadcasters in the world. In 1917, half a century earlier, Thomas had first set eyes on Colonel T. E. Lawrence, the British archaeologist turned warrior in flowing white robes who helped lead the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Turks. Thomas knew a story when he saw one. In articles, lectures, and newsreel footage, Thomas elevated the diminutive Englishman—he was only five foot three, with a laugh that could quickly become a giggle—into the towering Lawrence of Arabia.

I shook Thomas’s hand. My father, an illustrator, asked him the sort of question an artist would ask: What was the first thing that struck you visually when you looked at Lawrence? Thomas didn’t have to think. He said, “His head was too big for his body.”

The Prince of Mecca

The fateful meeting of soldier and promoter comes midway through Lawrence of Arabia, the engaging, deeply personal, sometimes slightly eccentric new study by the adventurer Sir Ranulph Fiennes. Thomas had been buying dates in the Old City of Jerusalem when a figure caught his attention: “The man was wearing an agal, a kuffieyeh, and an aba, such as are only worn by Near Eastern Potentates. In his belt was fastened the short, curved sword of a prince of Mecca.” But this prince of Mecca had blond hair and blue eyes.

At the moment of encounter, Lawrence’s capture of Aqaba lay in the recent past. The capture of Damascus lay in the near future. For more than a year, Lawrence and his Arab comrades had been attacking bridges and railways and otherwise harrying the Ottomans (and by extension their German allies)—a sideshow compared to the Great War in Europe, though highly successful and triumphantly cinematic.

But Lawrence was tormented by something he knew: even as they dangled independence before the Arabs, in secret the British were working with the French to carve up the Middle East for themselves. Lawrence wrote privately, “We are calling them to fight for us on a lie, and I can’t stand it.”

Ranulph Fiennes doesn’t offer some bold new interpretation. He follows the story told by Lawrence himself in Seven Pillars of Wisdom (1926), quoting him often. Lawrence may not always be reliable, but he could write. (Not to mention re-write: he lost the first draft of his book while changing trains at Reading Station after the war.) One tribal leader is memorialized like this: “Over his coarse eyelashes his eyelids wrinkled down, sagging in tired folds, through which, from the overhead sun, a red light glittered in his eyes and made them look like fiery pits in which the man was slowly burning.”

“We are calling them to fight for us on a lie, and I can’t stand it.”

What captivates Fiennes are the parallels between Lawrence’s experience and his own, starting in 1968, as a British officer in Oman, where the sultan was engaged in a campaign against the Dhofar Rebellion. “Your job, Fiennes,” he is told, “will be to lead an Arab platoon in Dhofar against the adoo”—adoo being Arabic for “enemy.”

Fiennes’s language, with its harrumphing understatement and mild imperial inflections, seems to come from another era. A previous officer in Oman had been sent home “after accidentally blowing the mess-boy’s head off when cleaning his rifle”—an incident, Fiennes notes, that “led to some ill-feeling.” He describes a moment when Lawrence must personally execute one of his Arab comrades—both to mete out justice and to save face—then shifts the scene to Oman: “I well remember a similar troubled feeling after killing a man for the first time.”

Lawrence had never seen action before joining, and then uniting, the fractious Arab tribes of the Hejaz. Until his service in the sultanate, Fiennes, too, had never seen action, unless one counts an attempted act of eco-terrorism in Wiltshire in the mid-1960s. (A demolitions expert, he attacked a stream-despoiling dam built for the movie Doctor Dolittle.)

One of Lawrence’s main objectives was to disable the Turkish railway system. Blowing up track became a priority, especially track that was curved, which was especially hard to replace. Lawrence pioneered a hybrid form of warfare, combining modern weaponry and guerrilla tactics. His Arabic became fluent. He rode camels like a Bedouin. Emir Faisal, a leader of the Arab Revolt (played by Alec Guinness in David Lean’s 1962 movie) gave Lawrence (played by Peter O’Toole) the white, gold-threaded robes that became his hallmark.

But there was nothing romantic about desert operations. At war’s end, Lawrence weighed not much more than 80 pounds. Heat, cold, hunger, thirst, pain, fatigue—these were the constants, along with “war, tribes, and camels without end,” as Lawrence himself would write. Falling briefly into Turkish hands, he was tortured and almost certainly raped, scarring him profoundly.

His Arabic became fluent. He rode camels like a Bedouin.... But there was nothing romantic about desert operations. At war’s end, T. E. Lawrence weighed not much more than 80 pounds.

One can’t read about Lawrence without thinking of all that has come to pass in the Middle East in the century since the Great War. With the breakup of the Ottoman Empire, imperial powers rushed in. As John Oliver (wearing a pith helmet) once explained to Jon Stewart on The Daily Show, “Look, there’s nothing the Arab respects … more than a strong, steady white hand drawing arbitrary lines twixt their ridiculous tribal allegiances.”

Lawrence tried to influence events on the margins—he submitted his own hand-colored map of what he saw as the Middle East’s “natural” boundaries to the British war cabinet—but no cartographic scheme would have been adequate to the convulsion. In his book A Peace to End All Peace, the historian David Fromkin noted that it took Europe 14 centuries to settle itself after the fall of Rome.

Lawrence was forever haunted by what he saw as Britain’s (and his own) betrayal of those who had fought beside him. He was haunted by much else—the killing he had done; the violation he had endured; his sexuality; his unwanted fame. Back home, he rode his motorcycle recklessly; an accident in Dorset took his life in 1935, at age 46.

As Fiennes makes clear, Seven Pillars of Wisdom is, among other things, a sprawling record of the angry turmoil inside Lawrence’s head. It really was too big for his body.

Cullen Murphy is an editor at large at The Atlantic and the author of several books, including God’s Jury and Cartoon County