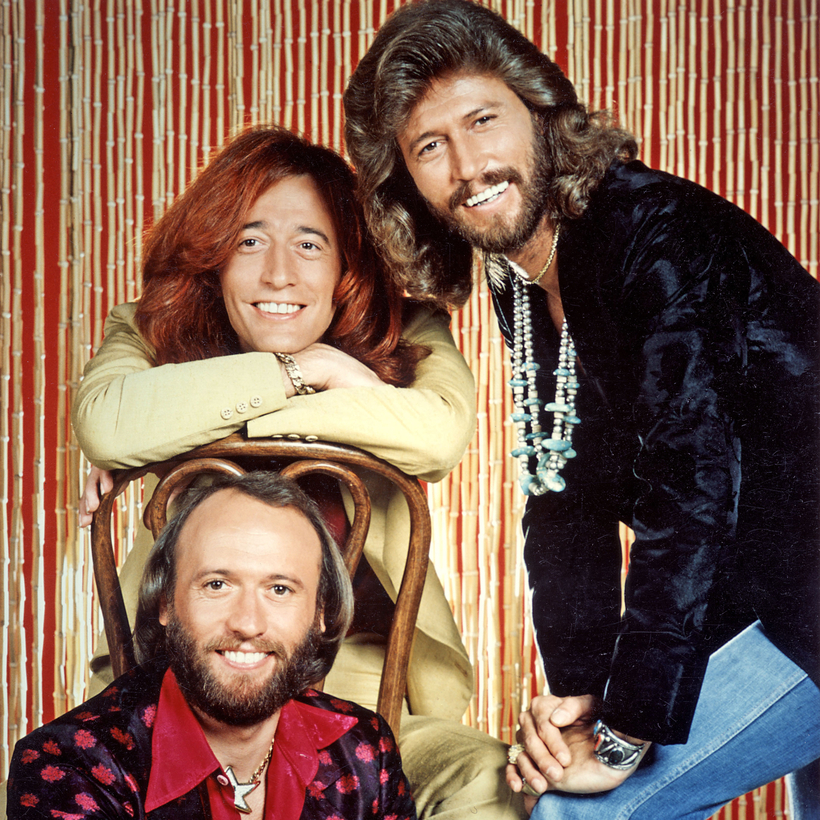

It was while hanging out in a stripper’s dressing room that an 11-year-old Maurice Gibb started questioning his life. “Will I be a normal child?” he wondered as he waited to go onstage with his twin, Robin, and elder brother, Barry, for the nightly club set their band fitted in after school. The answer came to him quickly: “No!”

Normality doesn’t have much of a part to play in the story of the Bee Gees, the band formed in Brisbane in 1959 by three recovering juvenile delinquents fond of the Everly Brothers and low-level arson. As Bob Stanley’s astute, affectionate biography Bee Gees: Children of the World stresses, there was nothing normal about an adolescence spent singing alongside dancing dogs and jugglers in rough Queensland clubs. There was nothing normal about their turbulent international career, either, with nine US No 1 singles, outstripped only by the Beatles and the Supremes.