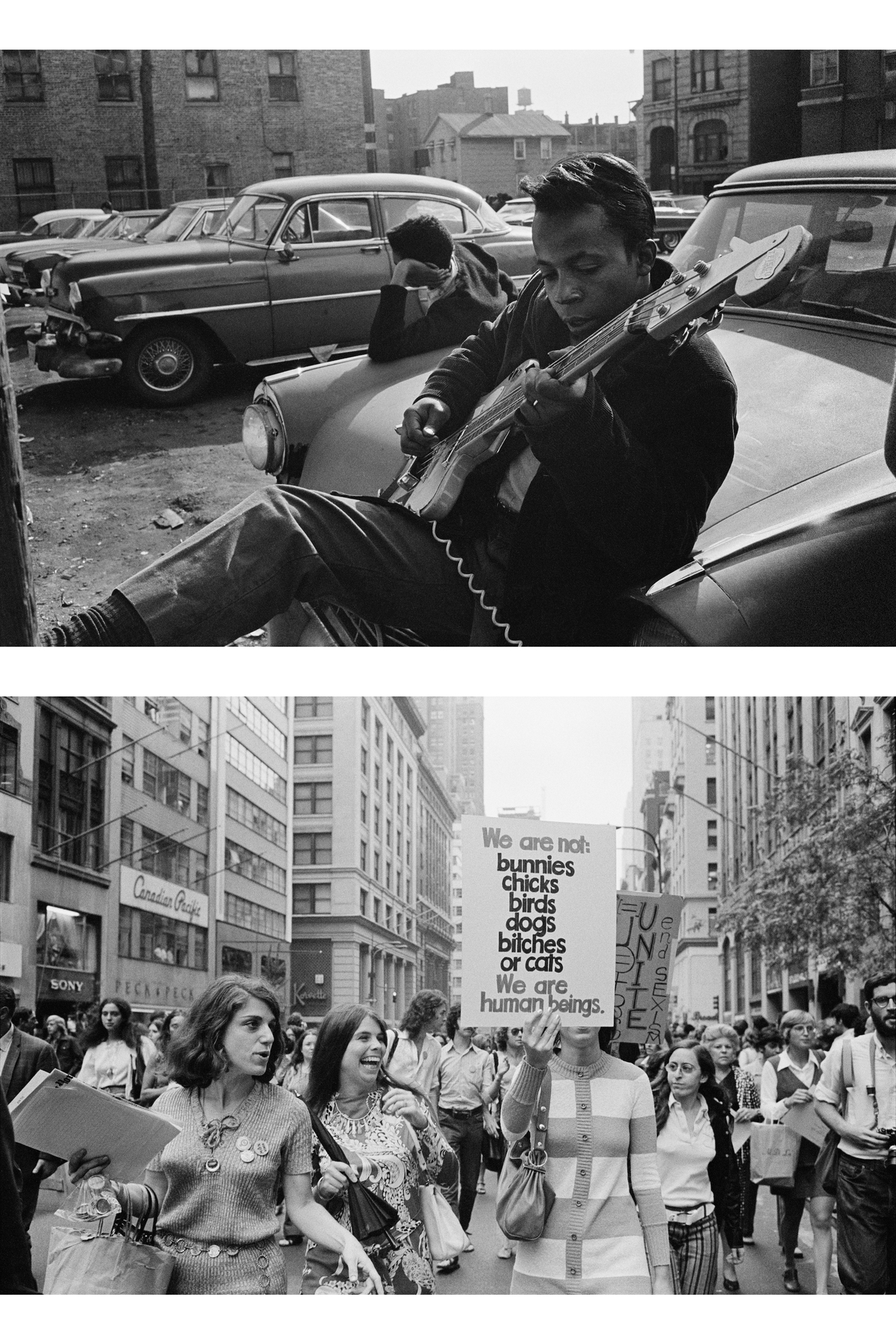

Ernest Cole’s life was defined by exile. In 1966, the photographer landed in New York from South Africa. He was still fresh-faced at 26, but he wasn’t in America by choice. Earlier that year, the authorities had arrested Cole for documenting Black life under the country’s hellish system of apartheid. By the time he’d landed in the home of the free, he was on his native country’s “banned list.”

In 1967, Cole’s House of Bondage was released, the first and only book of those early South African photographs published during his lifetime. Though it was widely acclaimed, and copies were sent to the chairman of the United Nations Special Committee on Apartheid, Cole refused to consider doing another book, which would have featured his American photographs. He said he still didn’t understand the country well enough.