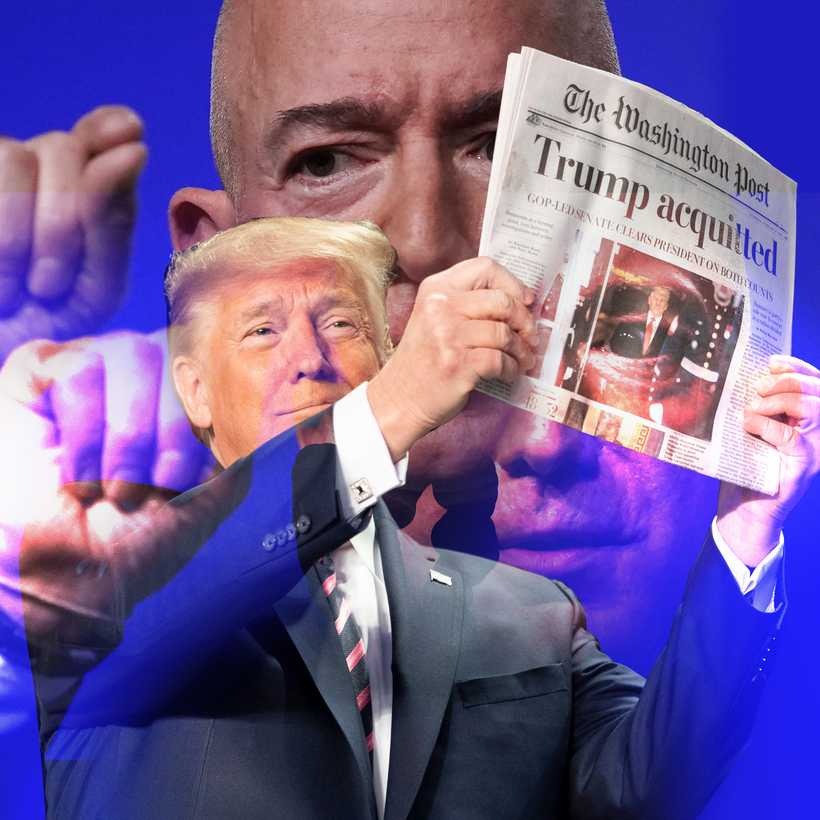

Collision of Power: Trump, Bezos, and The Washington Post by Martin Baron

Martin Baron has seen a lot of news in the news business. “Big stories seemed to erupt shortly after I became a publication’s new top editor,” Baron writes in Collision of Power: Trump, Bezos, and The Washington Post: the Elián González raid and then the Bush-Gore presidential recount, at The Miami Herald; the 9/11 hijackings out of Logan Airport and then the Catholic Church’s sex-abuse scandal, at The Boston Globe.

Here, near the start of Baron’s memoir of his term at The Washington Post, he is referring to Edward Snowden’s leaked documentation of the N.S.A.’s secret, omnivorous surveillance program in the spring of 2013—the Post’s most momentous story, in Baron’s estimation, since Watergate and the Pentagon Papers.