Rock ’n’ roll is full of con men and sleight-of-hand tricks. Deception is wrapped up in the genre’s DNA, running much deeper than rip-off record labels and greedy managers. It begins with the artists themselves, who spend a lifetime on stages and in recording booths, pouring their hearts out to anyone who’ll listen, but then, perversely, dying before you truly get to know them. The only thing that makes it bearable is that they leave behind their music. They stab you, but you get to keep the knife.

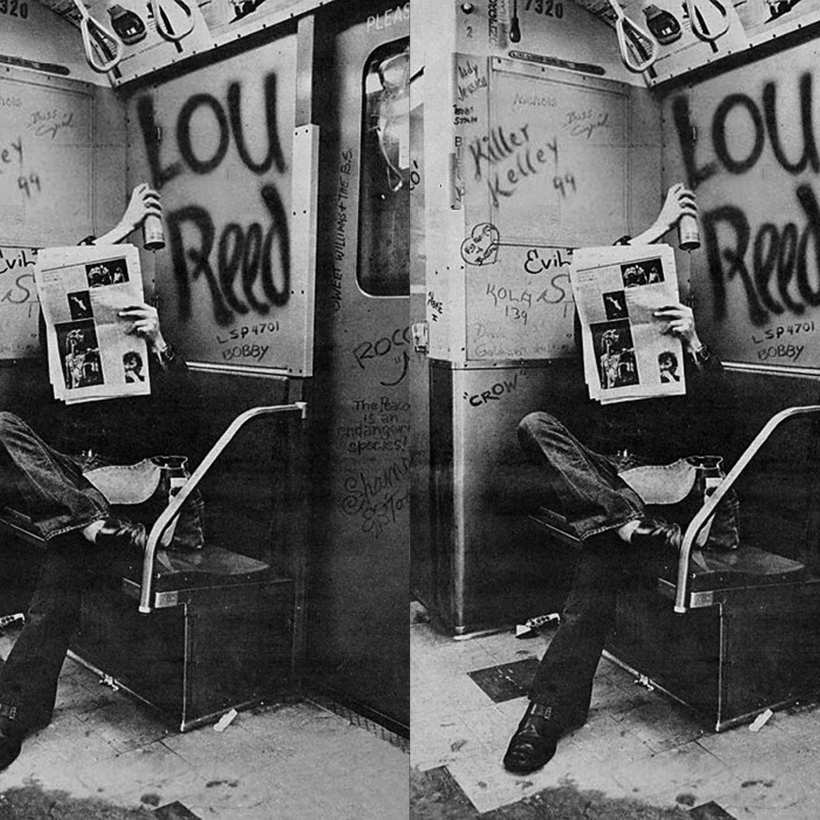

The king of this particular form of enchantment was Lou Reed. Until his death, 10 years ago, Reed practiced a sort of bewitching vagueness—Patti Smith described him as “elegantly restrained”—that makes the trove of songs he left behind (a copy of his collected lyrics clocks in at 679 pages) feel more like a decades-long koan than an answer to who Lou Reed was, biographically speaking.

So daunting is the task of digging through Reed’s past that Will Hermes devotes the preface of his new biography, Lou Reed: The King of New York, to pointing out how much the artist resisted being written about—when asked to define the lowest depth of human misery in Vanity Fair’s February 1996 Proust Questionnaire, Reed said: “being interviewed by an English journalist”—and to saying that he wouldn’t attempt a “neat totalizing statement” that fixes Reed “like a butterfly specimen.” The ensuing book follows Reed’s complicated waltz from middle-class Long Island boy to downtown bohemian icon and, finally, worldwide rock star, laying on the concrete details while resisting the urge to present a unified theory.

Under the banner of chapter headings that read as a list of Reed’s coordinates over the years—unsurprisingly, most are in and around New York City—Hermes makes it clear just how far ahead of everyone he was, musically and socially.

Will Hermes follows Lou Reed’s complicated waltz from middle-class Long Island boy to downtown bohemian icon and, finally, worldwide rock star.

Born in 1942, Reed had already left the Velvet Underground, the band in which he cemented his reputation as a streetwise bard as much as a musician, by the time many of his contemporaries were just getting started. David Bowie, Patti Smith, Jonathan Richman, Debbie Harry, Talking Heads, and others enter the fray like products of Reed’s influence, eager to take part in the downtown music scene he made look so devastatingly, dangerously sexy.

Yet, even though he adopted the workaholic tendencies of his friend and mentor, Andy Warhol, and the mercurial intensity of his teacher, the writer Delmore Schwartz, Reed doesn’t quite seem to belong to the older generation, either. He’s stuck in the middle between his guiding lights and his imitators, an inscrutable man of principle who’s adrift but can’t—or won’t—say why.

Many of the details in the book have been reported elsewhere before by people who were actually friends with Reed—such as in Anthony DeCurtis’s 2017 biography, and in There Goes Gravity by Lisa Robinson—but Hermes invokes them with a current tone that’s favorable toward, but not overly forgiving of, the notoriously prickly Reed. If you’re seeking an example of Reed’s testiness, look no further than his 1975 press conference at the Sydney Airport, in which he asks a reporter, “are you happier as a schmuck?” and claims, ludicrously, to have five imitators who play his concerts for him.

More than any previous biographer, Hermes allows a wide berth for the topics of sexuality, mental health, and addiction. He writes, “Without dismissing the importance of articulate queer role models, Reed’s insistence on a private life might be read as the empowered, self-caring decision of a public figure to keep parts of themselves off the celebrity trading floor.” Elsewhere, in describing the song “Waves of Fear,” the author speculates that a good deal of Reed’s behavior, from drug addiction and outbursts of anger to making music itself, was likely a response to the panicked anxiety he dealt with throughout his life. This is as close as the author gets to explaining Reed’s motivations and logic.

It’s worth noting that explaining Reed’s thinking, particularly in the 60s and 70s years of his career, would be difficult even for those who were in close proximity to the artist (Hermes was not). So many of the primary sources the book relies on were either drug addicts, alcoholics, or just plain crazy. Needless to say, accounts vary, and the upshot of even the best-researched biographies is that the modifier “definitive” has to be taken with a grain of salt.

Though Reed has gotten a lot of credit for being part of the musical avant-garde, it’s possible that he was even more progressive in writing and singing about his sexual fluidity (“And some kinds of love, the possibilities are endless / And for me to miss one would seem to be groundless”), drug use (“Aww I surely do love to watch that stuff tip itself in”), and history of electroconvulsive therapy (“All your two-bit psychiatrists are giving you electro shock / They say, they let you live at home, with mom and dad / Instead of mental hospitals”).

(On the last point, it’s difficult not to think of another master lyricist, country musician Townes Van Zandt, who was also given shock treatment in his youth. If this is the result, maybe we should be electrocuting more of our musicians.)

He’s stuck in the middle between his guiding lights and his imitators, an inscrutable man of principle who’s adrift but can’t—or won’t—say why.

One of the book’s finer moments is when Warhol enlists the speed-addled Velvet Underground to perform at a black-tie dinner for the New York Society for Clinical Psychiatry in 1966. The result, naturally, is complete chaos, with one attendee declaring, “I’m ready to vomit,” following a volcanic set that included the song “Heroin.” Hermes notes, “It’s conceivable that among the hundreds of New York–area psychiatrists in that room was the one that prescribed his electroconvulsive therapy years before.” Moments like these say more about Reed than he’d ever say about himself. Like any great magician, he always wanted you to see the trick rather than the man performing it.

But, like most people who play things close to the vest, Reed occasionally let his guard down. At the fourth annual Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony, in 1989, he gave a beautiful tribute to Dion DiMucci, who might well hold the title for the best voice in rock ’n’ roll history. Like Reed, Dion had struggled with drug addiction, and it wasn’t until Phil Spector helped him mount a comeback, with the album Born to Be with You (1975), that he was taken seriously as a musician again.

Recalling the doo-wop hits of his youth—among them Dion’s songs “Runaround Sue” and “The Wanderer”—Reed explained how the splendor of their unadulterated longing filled his teenage mind “like Shakespearean sonnets, with all the power of tragedy.” It’s here that we begin to understand what Reed was trying to get at, beyond the cool attitude and drugs and city grit. For him, the sport of rock ’n’ roll was about how to represent feelings in the plainspoken poetry of his youth, like Alicia & the Rockaways’ “why can’t I be loved.”

Reed finished his speech by asking, rhetorically: “Who can be hipper than Dion?” It took a disappearing act to make us realize that the answer to that question is Lou Reed.

Nathan King is a Deputy Editor at AIR MAIL