Hark! Ashton Kutcher, the arbiter of truth, owner of divine intuition, has broken his silence once again. Since descending unto the masses, in the early aughts, the actor has proven himself an orator of the highest acumen. His intellect had been sharpened by his participation in the cerebral masterpieces Dude, Where’s My Car?, Two and a Half Men, and the particularly scholastic My Boss’s Daughter. When the architect behind Punk’d speaks, one would do well to listen.

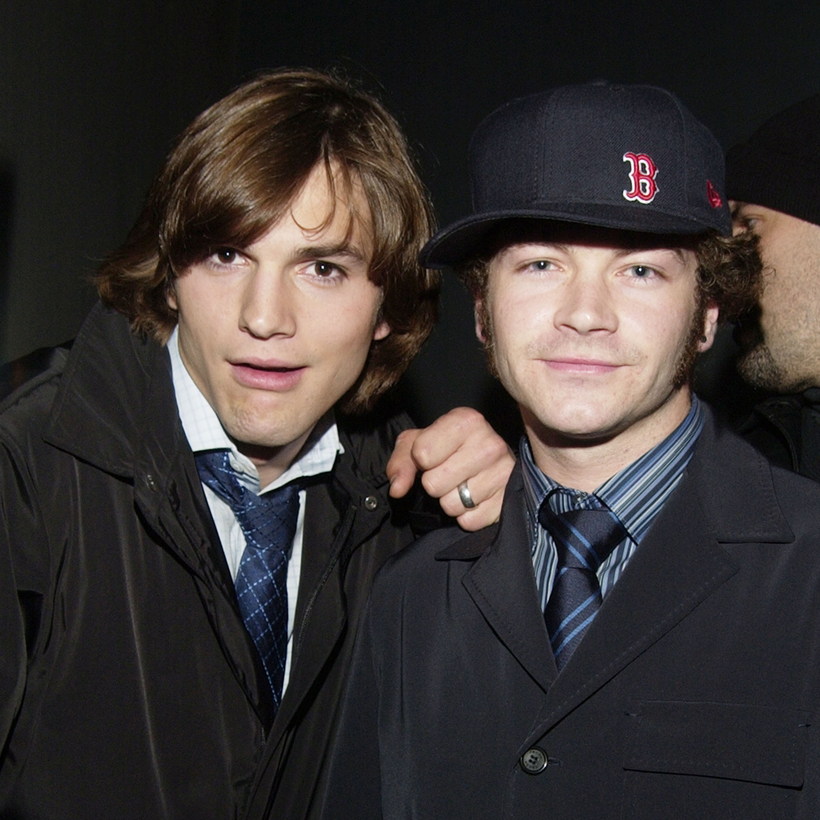

Alas, even the shrewdest sage cannot throw only strikes. Kutcher’s most recent pitch, a character defense of his That ’70s Show co-star Danny Masterson, who this month got sentenced to 30 years to life in prison for the rape of two women, was evidently an ill-fated gospel. “He’s an extraordinarily honest and intentional human being,” Kutcher wrote in a letter to the Honorable Judge Olmedo ahead of the trial. “Intentional”? An uncharacteristic faux pas. “As a role model, Danny has consistently been an excellent one,” he continued. “I do not believe he is an ongoing harm to society…”