Back in 2016, the Public Theater held a top-secret workshop of Stephen Sondheim’s new musical, Here We Are, based on director Luis Buñuel’s movies The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and The Exterminating Angel. The first act was fine, with, a source told me at the time, “gorgeous music.” The second act was a problem—in fact, it barely existed. Sondheim had run dry.

Producer Scott Rudin planned to launch the show at the Public and then move it to Broadway. But he needed more songs. They did not come. He told the then 86-year-old Sondheim, “Steve, the actuarial tables are not on our side.”

When Sondheim died, in 2021, it appeared that Here We Are was dead, too. But director Joe Mantello and writer David Ives did not give up on it. They have painstakingly pulled it together with the help of one of Sondheim’s longest and most trusted collaborators, Jonathan Tunick, who has orchestrated nearly every Sondheim show since Company, including Follies, A Little Night Music, and Sweeney Todd.

Tunick can’t discuss Here We Are just yet—everybody on the show had to sign a confidentiality agreement that runs until its first preview, on September 28, at the Shed in New York—but sources say he has taken sketches of Sondheim songs and fleshed them out for the second act.

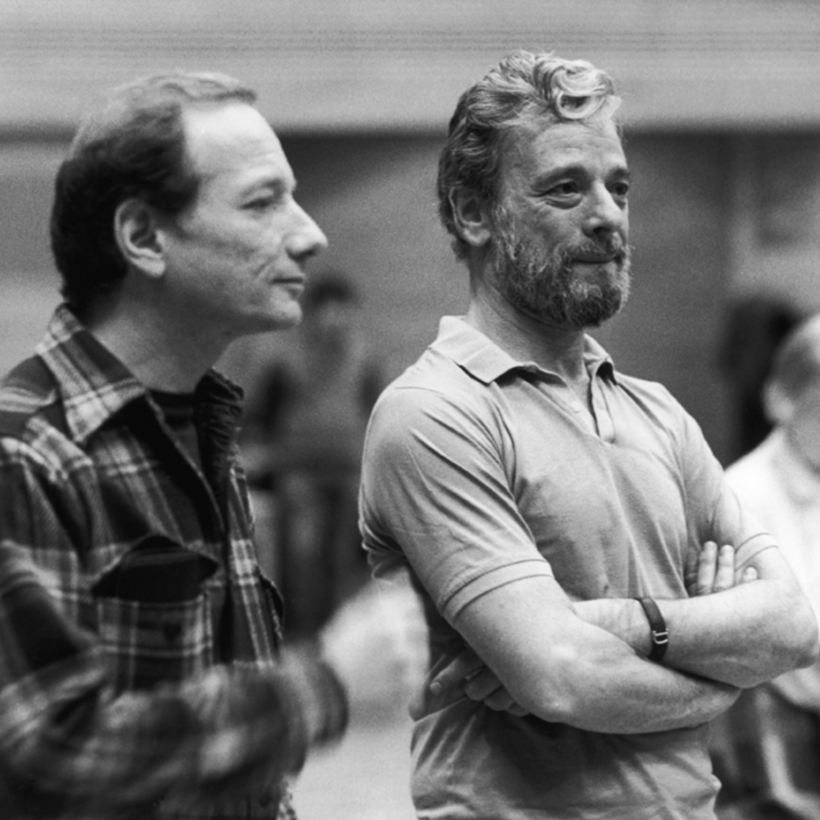

And nobody knows where Sondheim intended to go musically better than Tunick. “I used to go over to Steve’s town house to hear a new song,” he says. “I would sit at the piano bench next to him and turn the pages. He would sing as best he could, growling out the melody, usually an octave below pitch. I’d say, ‘F-sharp sounds a little funny. Did you mean that?’ And he’d say, ‘Yes, I meant it.’ Then he’d laugh and say, ‘Well, you’re right. I meant F-natural.’”

A modest, private man who does not seek the spotlight, Tunick, 85, is the best Broadway orchestrator since Robert Russell Bennett, who orchestrated musicals for Jerome Kern, Richard Rodgers, and Cole Porter. Tunick is also an EGOT, having won an Emmy, a Grammy, an Oscar, and a Tony. He has them on his coffee table. The Emmy, which he won in 1982 for Night of 100 Stars, has fallen from its stand. “They were cheap back then,” he says, laughing.

Tunick grew up on New York’s Upper West Side and learned to play the clarinet when he was eight. He was not a Broadway fan as a kid. “The music, frankly, sounded a little stodgy,” he says. What he loved was jazz, and the clarinet playing of Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, and Buddy DeFranco. He remembers walking the family dog one night along 69th Street and hearing live music wafting out of an open window of a brownstone: “It was modern jazz. I’d never heard anything like it before. It had intonations, good phrasing. I stood there listening for an hour. I have no idea who those guys were, but they must have been the best.”

“Steve, the actuarial tables are not on our side.”

Tunick was studying music at Juilliard when a friend gave him the cast album to A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, the first Broadway show for which Sondheim wrote both music and lyrics. Tunick knew Sondheim’s lyrics from West Side Story and Gypsy but didn’t know he also wrote music. When Tunick heard the overture to the musical comedy, “I was going through the ceiling,” he recalls. “The notes keep going down and down, lower than you ever thought they would dare. I knew then that this guy was a great composer.”

Through mutual friends, Tunick met Sondheim. Tunick had scored an Off Broadway musical, which Sondheim liked. He asked Tunick to work on Company. Right away Tunick understood something about Sondheim’s music: “Even though it sounds like popular songs, it’s much more like contemporary classical music. He writes like [Francis] Poulenc or [Darius] Milhaud. Once that had settled in my brain, I knew that was the way to go.”

Sondheim valued Tunick not only for his musical abilities but also his dramatic instincts. His arrangements captured what Sondheim’s characters were thinking and feeling. “In Buddy’s Eyes,” from Follies, is a good example. Whenever the character is thinking about Buddy, the love of her life, “the orchestra swims with ecstasy,” says Tunick. “When she doesn’t talk about Buddy, the arrangement becomes dry and bony. What’s important is the contrast.”

When Sondheim gave him “Not While I’m Around,” from Sweeney Todd, Tunick set the jarring notes to a solo violin. If not handled properly, a solo violin “can be treacly,” Tunick says. “But I had the idea of a sweet, gentle … sound playing notes that are ugly.” The result: A song that is gorgeous and menacing at the same time.

Tunick remembers being in Boston for the out-of-town tryout of A Little Night Music. Hal Prince, the director—“a force like El Niño,” says Tunick—was demanding changes. Sondheim, a procrastinator, was hiding. Finally, he handed Tunick a new song.

“We need it in the show tomorrow,” Sondheim said. “And we need 30 seconds of music under the dialogue before the song starts.”

Tunick set those 30 seconds for the clarinet to create an atmosphere of poignancy and regret. Then he brought in the strings to begin the song. It was called “Send in the Clowns,” and it became Sondheim’s biggest hit.

Tunick saw Sondheim for the last time on October 5, 2021. Tunick was being honored at a theater in Connecticut, where he has a weekend house. He knew Sondheim usually shunned such events. But he invited him anyway. To his surprise, Sondheim accepted.

“He came to the concert and sat in the middle of the house,” Tunick says. “He went to the reception, got sloshed with the actors, and had a terrific time. I said, ‘I want to tell you how important it’s been to be with you all these years.’ He cringed. He hated sentiment. And then he put his arm around me and said, ‘Jonathan, we’re lucky that we met each other.’

“It was a typically Sondheimian understatement. But it was a fitting good-bye.”

Previews for Here We Are begin at the Shed’s Griffin Theater on September 28

Check out AIR MAIL’s Arts Intel Report, our newly revamped research tool for what to do and where and when to do it

Michael Riedel is the co-host of Len Berman and Michael Riedel in the Morning, on 710 WOR, and the author of Razzle Dazzle: The Battle for Broadway and Singular Sensation: The Triumph of Broadway