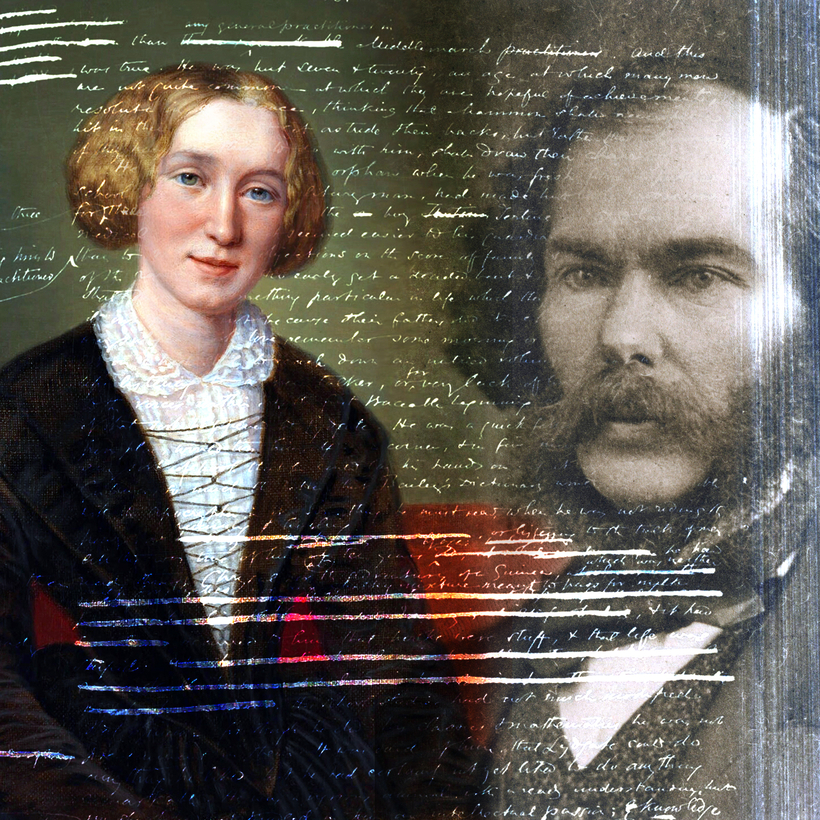

In October of 1856, Mary Ann Evans, a successful English essayist and editor, wrote a scathing essay in The Westminster Review entitled “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists,” criticizing the majority of novels written by and for women for being permeated with “the frothy, the prosy, the pious, or the pedantic.” At the same time, Evans—soon to become George Eliot—was struggling to begin her first foray into fiction, a long-held ambition.

So far, she’d been discouraged by the philosopher George Lewes, her spiritual, intellectual, and romantic soulmate, her “husband” in every way except legally, who claimed she was “without creative power.” Yet, that summer, Lewes relented, urging her to write a short story, her “wit, description, [and] philosophy” lending itself well to the genre. He was transparent about his change of mind—he needed to pay off the huge debts of his legal wife, Agnes, and fiction was more lucrative than nonfiction. Eliot, desirous that their “marriage” in every way mirror a real one, had insisted her earnings be deposited directly into Lewes’s bank account.

The best marriages—legal, spiritual, and otherwise—are deeply complicated, problematic, nuanced, co-dependent, foundational, tricky. Clare Carlisle, in her intriguing, often brilliant book The Marriage Question, guides us, by way of biography, philosophy, literary interpretation, literary history, and the histories of art and religion, through a profound consideration of Eliot’s unconventional “marriage,” and how that emotional—and, in many ways, strategic—choice influenced her life and career.

A central question in Carlisle’s book is one Eliot often posed to readers of her novels: Under what conditions can women find creative expression and fulfillment given extensive, often prohibitive, cultural, legal, and societal barriers?

Destiny’s Child

Eliot was born into a lower-middle-class, conservative Anglican family in rural England. Marriage was her destiny. Her physical appearance, however, fell short of the feminine ideal. She had a long chin, gray eyes, crooked, protruding teeth, and “that magnificent nose which drew comparisons with the physiognomy of John Locke, Dante, and Savonarola.” Eliot yearned for someone to share her life and ambitions with, but she was also fully aware that marriage, rather than nurturing creativity in a woman, was often the harbinger of its death.

As a young woman, she’d formed powerful and formative intellectual relationships with a number of female friends, some of which evolved into near-romantic attachments. But Eliot, a conformist at heart, resisted the pull of erotic female friendships, opting instead, after a series of disappointing traditional courtships, for a married man. George Lewes was a cultural critic, editor, physiologist, and frequently the most entertaining and engaging person in the room. He was also wry, flippant, irreverent, and, to some, irritating. Eliot fell in love.

Eliot would suffer terribly throughout her life—she was prone to depression—from the unconventionality of her liaison with Lewes, losing many friends and provoking the rejection of her family. She was also not welcome in “polite” society. But Lewes truly understood and adored her, recognizing her significant talent, indeed, her “genius,” as a writer. “He was steadfastly cheerful through her recurrent depressions,” writes Carlisle, “relentlessly encouraging through her self-doubt … putting her work before his own—answering her letters to give her time to write, poring over reviews of her books.”

When Evans finished her first short story, “The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton,” Lewes sent it to his publisher, John Blackwood, accompanied by a letter full of praise for the story and its “shy, shrinking, ambitious” author. Aware that their status as adulterers would impinge on her chances of publication, much less success, they came up with the pseudonym George Eliot. Mary Ann (or Marian) Evans would thus lose her “maiden” name and gain others: George Eliot, the nickname Polly, and Mrs. Lewes, which she and Lewes insisted others use when addressing her.

Several more stories were soon published in Blackwood’s Magazine and eventually collected into the book Scenes of Clerical Life, favorably greeted by the critics and public alike. Many extraordinary novels followed, including Adam Bede, The Mill on the Floss, Silas Marner, Romola, Middlemarch, and Daniel Deronda, leading to Eliot’s worldwide renown.

Though she counted among her close friends some of the most prominent radical feminists of the day, most notably Barbara Leigh Smith Bodichon, co-founder of Girton College, Cambridge’s first women’s college, Eliot would not have described herself as a feminist, even if her entire body of work explores and exposes the injustices women have been subjected to across history.

Soon after the publication of Adam Bede, in 1859, Bodichon wrote to Eliot claiming she’d immediately identified the true author, recognizing in the prose “her big head and heart and her wise wide views.” Eliot replied with an appreciative letter to which Lewes added a footnote: “Over 3000 copies have been sold already and as 500 is a good success for a novel, you may estimate by that detail what my Polly has achieved. But, dear Barbara, you must not call her Marian Evans again: that individual is extinct, rolled up, mashed, absorbed in the Lewesian magnificence!”

In her book, Carlisle deftly teases out how Eliot navigated her union with Lewes—what Eliot called her “double life, which helps me to feel and think with double strength”—to best serve her ambition, which reached, according to Carlisle, “for the greatness of Wordsworth, Milton, Shakespeare, Dante, even of Euripides and Sophocles.”

Eliot’s and Lewes’s lives were intricately, inextricably interwoven, Eliot believing, Carlisle shows, that “love and dependence are inseparable. From birth to death a human being is never independent, and should not strive to be. On the contrary, a deeper awareness of dependence nurtures emotional growth.” Early on, Eliot had a strong intuition for what she needed from a romantic partner in order to achieve her desired greatness, even if that meant ceding considerable control over herself and her earnings.

Ultimately, Carlisle’s thoughtful, comprehensive account of this particular liaison exquisitely probes the complex, thorny, and fascinating question: How much does our choice of partner determine who we ultimately become?

George Eliot wished to be buried in Westminster Abbey’s Poets’ Corner, alongside Dickens and Chaucer. Her scandalous union did not allow her wish to come true. Instead, she was buried in an unconsecrated part of Highgate Cemetery, next to Lewes. In 1980, on the centenary of her death, a stone was finally laid in Poets’ Corner, commemorating Eliot’s contribution to English literature.

Jenny McPhee is a writer and translator and the director of the Center for Applied Liberal Arts at N.Y.U.’s School of Professional Studies