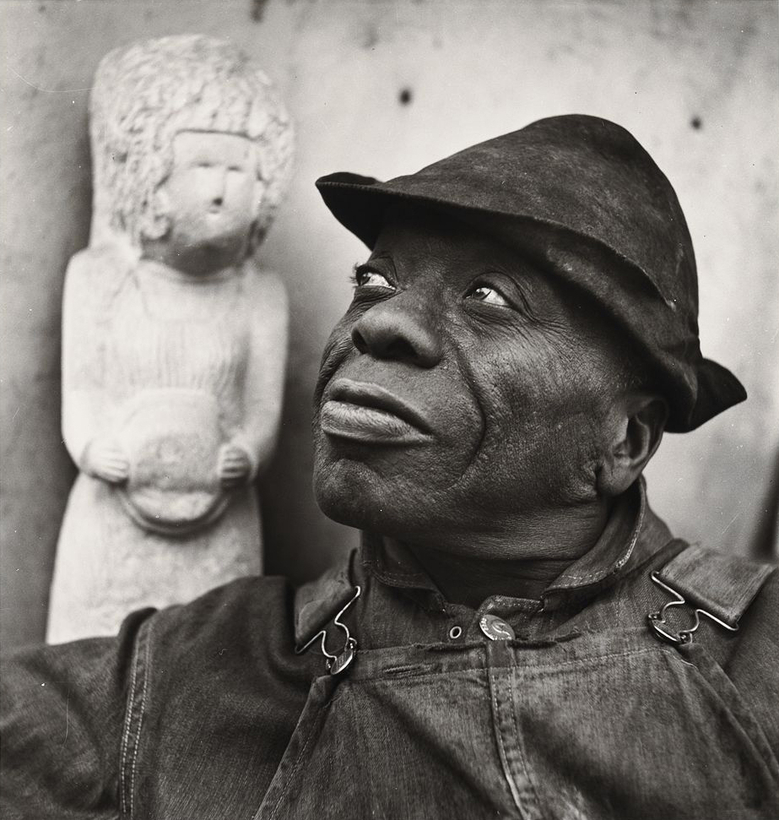

In 2016, 65 years after the self-taught sculptor William Edmondson was buried in an unmarked grave, his work Boxer fetched $785,000 at Christie’s—breaking the sales record for a single piece of “outsider art.” Born in 1874 in Davidson County, Tennessee, the son of sharecroppers, Edmondson settled in Nashville, where late in life he carved gravestones for neighbors and made art for his community, fashioning biblical figures, animals, preachers, and teachers from limestone. “William Edmondson: A Monumental Vision”—now on at the Barnes Foundation, in Philadelphia—celebrates the artist with 66 of his works as well as photographs of his home, by Louise Dahl-Wolfe and Edward Weston.

The exhibition attempts to revise the way Edmondson’s story is told. Nancy Ireson, the deputy director for collections and exhibitions at the Barnes, says it is important to push back on the idea that white collectors “discovered” the artist. As the lore goes, Sidney Mttron Hirsch, a Jewish model and playwright with connections to the Vanderbilts and the magazine Harper’s Bazaar, convinced Dahl-Wolfe to photograph Edmondson’s work and show it to gallerists and curators in New York. This led to Edmondson’s becoming the first Black American artist to receive a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), in 1937.

“Our survey emphasizes the role Edmondson played in his community,” says Ireson. “Kelli Morgan [the director of curatorial studies at Tufts University] reminds readers of our catalogue that the artist had a career working for the people around him far before MoMA took an interest.” Whereas the press release for the MoMA show described Edmondson as a “modern primitive,” he described himself as “a disciple of Jesus.”

The contrast between how Edmondson talked about his work and how MoMA did is emblematic of the way Black folk artists have been characterized by the artistic establishment. Furthermore, his vision and voice, fully formed, already had a congregation. James Claiborne, curator of public programs at the Barnes, says that when he sees figures such as Edmondson’s Preacher, he can “almost hear the hoop and holler of the sermon.” He’s also drawn to Mermaid, which he says shows Edmondson’s ability “to master material and to do so with mystical and monumental vision.”

Since 2018, in honor of his legacy, Edmondson’s descendants and the families of those who knew him have led a grassroots movement in Nashville’s Edgehill community to preserve the park where his home once stood. “There’s a tension around his emergence in the North taking him out of a Nashville context,” says Claiborne. “We are about co-authorship with communities, and sharing in the authority of a museum and the interpretation of history and artwork.”

In an attempt to bridge the divide between the narrative that white purveyors built around Edmondson and how Edmondson defined himself, Claiborne has commissioned a choreographic work from the artist Brendan Fernandes. It’s called Returning to Before, and it will be performed in the exhibition space on Saturdays.

“When I think about the stone,” Fernandes says, “I think about Edmondson’s gesture of moving his body to make an object take on form. To me, that’s choreography. It’s dance. You have these stone bodies that almost look soft, and some of the dancers’ positions mimic those shapes and forms. I do a lot of performances in spaces where African art is displayed out of context. Most African objects danced. There’s a sense that these objects are calling for a revitalization.” —Kelundra Smith

“William Edmondson: A Monumental Vision” is on at the Barnes Foundation, in Philadelphia, through September 10

Kelundra Smith is an Atlanta-based arts journalist and playwright. She writes primarily about Southern art and history rooted in the African diaspora

Discover

Discover