The Mille Miglia is known as the world’s most beautiful motor race: a 1,000-mile blast down the eastern calf and up the northern shin of Italy, from Brescia to Rome and back again, roaring through 200 peach-colored towns. The sidewalks are packed with cheering crowds. Priceless vintage automobiles swerve through oncoming traffic. Policemen blow their whistles and shout “Avanti! Avanti!” in encouragement. It could only ever happen in Italy.

The event was established in 1927 by four young men who wanted to put their town, Brescia (close to Lake Garda, between Milan and Verona), on the international sporting map. Two were newspapermen, two were aristocrats, and they were all mad about cars.

It fell to Count Aymo Maggi to use his considerable charm to secure all the permissions that were needed, along with the support of Italian prime minister Benito Mussolini. Maggi would host foreign racers in feudal style on his Calino estate. Seventy-seven cars entered the inaugural race, with each entrant paying a nominal one lira. Fifty-one made it back to Brescia, with winner Giuseppe Morandi completing the course in his two-liter OM in 21 hours and five minutes.

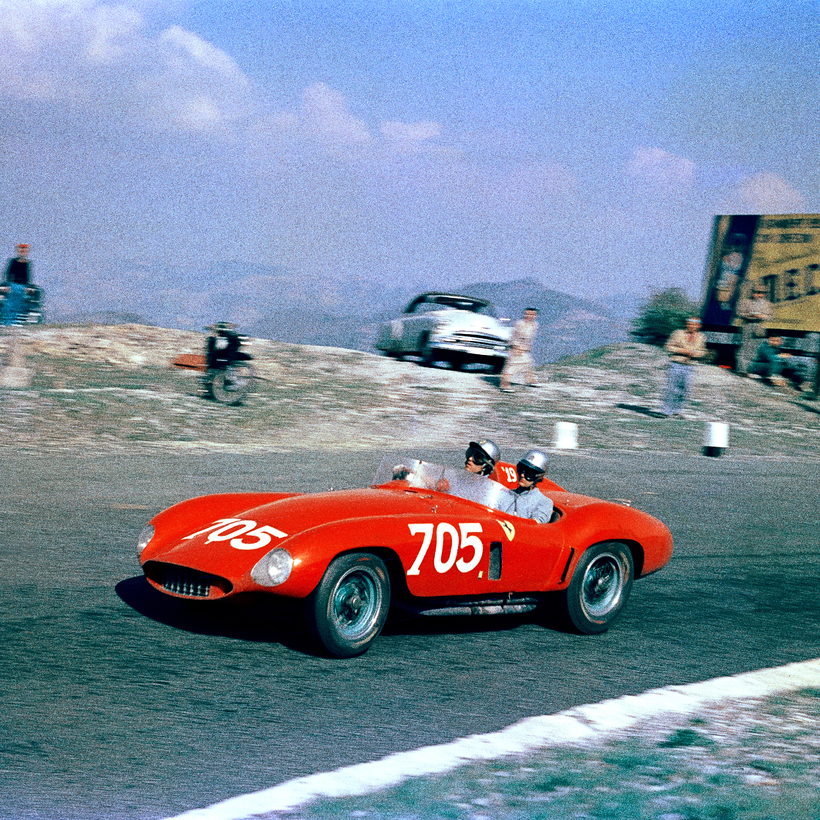

After the war, the Mille Miglia started to attract vast numbers of competitors. Not only the great marques such as Alfa Romeo, Ferrari, Maserati, and Mercedes-Benz, but many amateur drivers in their family cars—ordinary, inexpensive, four-door run-arounds—reaching a peak of 521 starters in 1955. Ferruccio Lamborghini, who built tractors before founding his eponymous supercar company, entered a humble Fiat Topolino and crashed it into an osteria.

The most iconic performance was Stirling Moss’s in 1955, racing the state-of-the-art Mercedes 300 SLR. The Englishman, with motorsports writer Denis Jenkinson navigating alongside him, covered the 1,000 miles in just 10 hours and seven minutes. Average speed: a jaw-dropping 98 m.p.h., mostly on unsurfaced roads. That car, which today sits in the Mercedes-Benz Museum, in Stuttgart, is probably the most valuable car in the world—worth north of $200 million.

The final installment of the original race was held in 1957. A factory-entered Ferrari went off the road, killing not only Alfonso de Portago and his co-driver, but nine spectators—including five children. Unsurprisingly, the authorities put an end to the race.

But in 1977, the Mille Miglia was resurrected as a rally, with prizes for time trials rather than outright speed, spread over four or five days rather than a single stint, and sharing the road with ordinary motorists going about their business, rather than being held on closed roads. Classic-car owners—this year, 443 of them—come from around the globe to experience a kind of time travel and to enjoy the ultimate Italian road trip.

Those from the U.S. and Japan spend at least $40,000 each to fly their cars over. The vehicles must have either participated in the 1927–57 race or be of an identical model. There is a certification process. Entry fees start at $13,650 per car, but, in addition to a race number, owners receive a limited-edition watch from the title sponsor, Chopard (its president, Karl-Friedrich Scheufele, has driven his Mercedes 300 SL Gullwing here every year for the past three decades). Recent participants have included Rowan Atkinson, Yasmin Le Bon, and Jeremy Irons.

Last month, I experienced the Mille Miglia in a pair of period Mercedes: a stately pre-war roadster for the early stages, and a super-sleek 1950s coupe for the final blast to Brescia. I met the rally in Rome at the end of the second day, with Stage 3 taking me to Parma, Stage 4 to Milan, and the fifth and final sprint to the checkered flag in Brescia for Franciacorta, the region’s sparkling wine, and medals.

The Mercedes 300 SLR, which today sits in the Mercedes-Benz Museum, in Stuttgart, is probably the most valuable car in the world—worth north of $200 million.

But first, I texted my friend David Gandy for tips. The fashion model is a Mille Miglia veteran, always at the wheel of a Jaguar XK120. “Don’t drive like an Englishman,” he warned. “Drive like an Italian. Don’t queue, just overtake everything. My favorite game on the MM,” he added, “is to hunt down anything German—especially the Gullwings.”

I didn’t mention this last bit to Marcus Breitschwerdt, head of Mercedes-Benz Heritage. He would be driving me in a fire-engine-red 1930 710 SS. This very rare vehicle is closely related to the car with which the legendary German grand-prix ace Rudolf Caracciola won the race in 1931. Our car, Marcus estimates, is worth somewhere between $13 million and $27 million. The transmission is non-synchronous, meaning one has to double-clutch, and the brake and throttle are the wrong way around. Due to all of the above, I’m very happy to be tasked not with the steering wheel but with the road book (an inch-thick document detailing every intersection we’d encounter in one day), the timing equipment and odometer, and, crucially, the horn.

The car’s hood, which encases a 7.1-liter supercharged straight-six, is about a mile long. It’s decorated with hundreds of louvers and secured with leather straps. The wheel arches are flared. From the cabin, the chrome headlamps allow you to admire the bodywork stretching back and the sky above. The radiator is capped by a ramrod-straight three-pointed star, and one is reminded of Indiana Jones hanging on to such a symbol until it snapped.

When Marcus puts his foot down and the compressor kicks in, it makes a noise like an elephant trumpeting. Like for anything of geriatric age, though, mountain climbing is a challenge. She—for I’ve christened the car Gertrude—crosses the Apennines at an average speed of 18 m.p.h., and we top up the water at regular intervals. We reach Parma after 18 hours of driving, exhausted.

Katarina Kyvalova’s 4.5-liter Bentley is of a similar vintage. “I’d never do it in anything else,” she tells me. “You sit nice and high, there’s loads of space, and the long bonnet makes it safer than some.” Katarina sells European real estate to Chinese buyers and lives between Hamburg and Majorca. Her obsession is old British cars. She also owns a Speed Six and an eight-liter Bentley, an E-Type Jaguar, and a Cooper-Jaguar T33.

Katarina’s only concession to modern motorsport is the Mercedes-AMG GT4 with which she competes in the Dubai 24 Hour and 24 Hours of Portimão races. Not to mention that both her Bentley and Gertrude are running on eco-conscious synthetic fuel for the first time, at $30 a gallon.

“The welcome we get on the Mille Miglia is magical. A little girl, seven years old, gave me a painting she did of me in my big green car. I’d driven through her town in the Bentley two years ago, and she and her mother sought me out to give me this wonderful painting.”

“Drive like an Italian. Don’t queue, just overtake everything.”

For the final stage, I take the wheel of what has always been a dream car of mine: a 1954 300 SL Gullwing. It handles even more gracefully than I’d hoped.

Speed limits don’t really seem to apply on the Mille Miglia. Through some provinces, we’re given a police escort, making a new lane down the middle of the road. The cops hold back the traffic, and we tear through the red lights. I’m told one police motorcycle clipped an oncoming vehicle. The rider was thrown in the air, and his bike ricocheted into a Ferrari. Once it was established the cop had “only” suffered a broken leg, attention immediately turned to the injured Ferrari. Faces were ashen and lower lips were bitten.

Make no mistake—the Mille Miglia can still be dangerous. “You’ll never hear what happened,” Katerina says of accident details. “It’s never reported.” Risk has always been part of the seduction of motor racing, though when some of the cars are worth seven or eight figures and there are no barriers between you and pedestrians, it pays to be conservative with the calculation.

Diego Carloni entered his Renault-powered Ferry F750, which first competed in the 1956 Mille Miglia. “It’s long and it’s tiring, but it’s a dream,” he says, “so long as you come back home.”

In Milan, a red Gullwing attempts to not stop at a zebra crossing. A man who is mid-stride crossing the road gets extremely irate with the driver and slams his fist down on the $2 million hood. Apart from this, I only saw love for the cars and the enthusiasts who brought them. Thousands of men and women across the north of Italy, children and great-grandparents and all ages in between, came out to watch these handsome and evocative art pieces in action, just like generations before.

These days, it sometimes feels like we petrolheads are pariahs, and that the pleasure of driving is being curtailed by anti-car legislation. But it was heartwarming to find that in Italy sports cars are still celebrated. For the collectors who come here with their four-wheeled pride and joys, the affection is mutual.

Alan George, who flew over from Los Angeles to experience his first Mille Miglia, said at the finish line, “I feel like we just mainlined Italy.”

Adam Hay-Nicholls is the author of the upcoming Charles Leclerc: A Biography and Smoke & Mirrors: Cars, Photography and Dreams of the Open Road