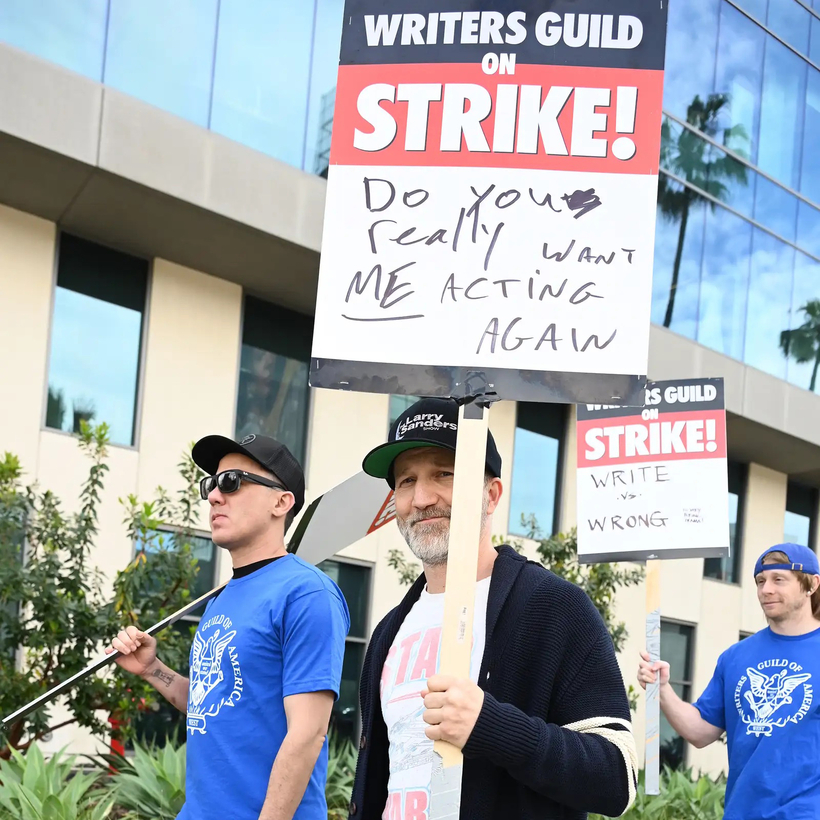

I’m on strike. Most of my friends are on strike, too. Each weekday morning, we text about which of the struck companies we should go picket, choosing from the available options like we’re pairing a wine with our entrée. It’s hot today, and we’d like a quieter walk in the shade but don’t want to drive too far—let’s go with Disney.

Each of the picket locations has a sort of micro-culture reflective of which writers can afford to live nearby. Fox and Amazon, on the west side of Los Angeles, are breezy and relaxed, populated by sun-kissed boomers wearing straw hats and a quarter-zip from Crossroads School. They built their careers in the halcyon days of syndication and beefy residuals.