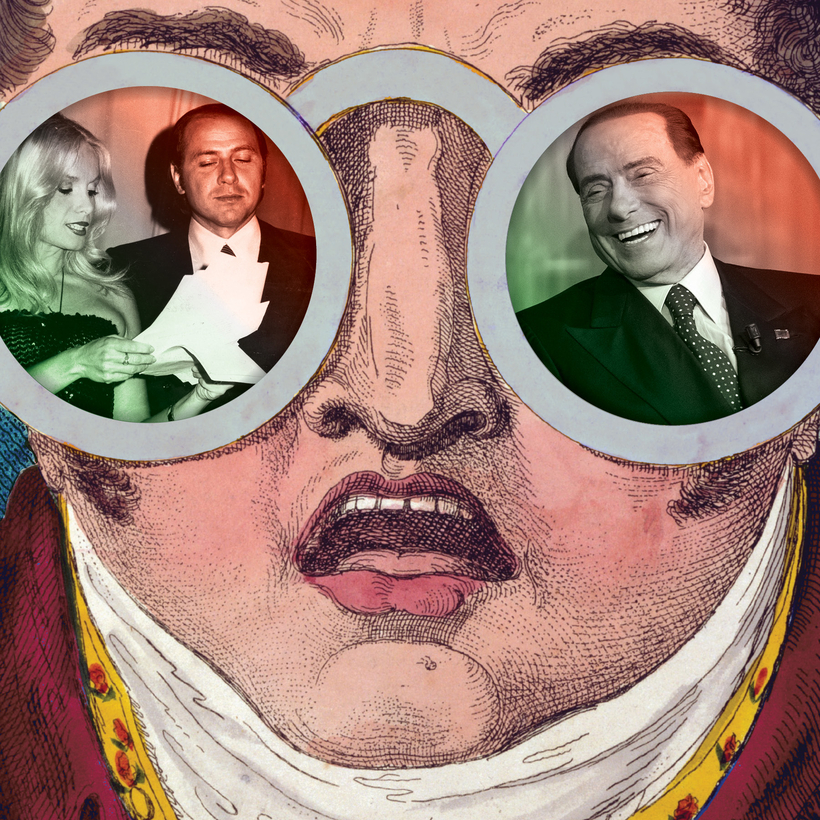

Silvio Berlusconi was Trump with a human face.

And that means that the two men had a lot less in common than most Americans think. The former Italian prime minister, for all his bluster, spray tans, and showmanship, was loyal to Europe and the Atlantic alliance and even the Italian constitution—well, at least the parts of it that didn’t clash with his criminal-defense strategies. Berlusconi was often provocative, but he was far more disciplined and worldly than Trump and not at all as destructive, vengeful, and hate-filled. Truthfully, at times he was a lot of fun.