Artificial intelligence, in case you hadn’t heard, is about to take your job, upend society and, after that, perhaps destroy all humanity. And the man who has thrust us into this head-spinning new age? A Taiwanese immigrant who used to clean lavatories.

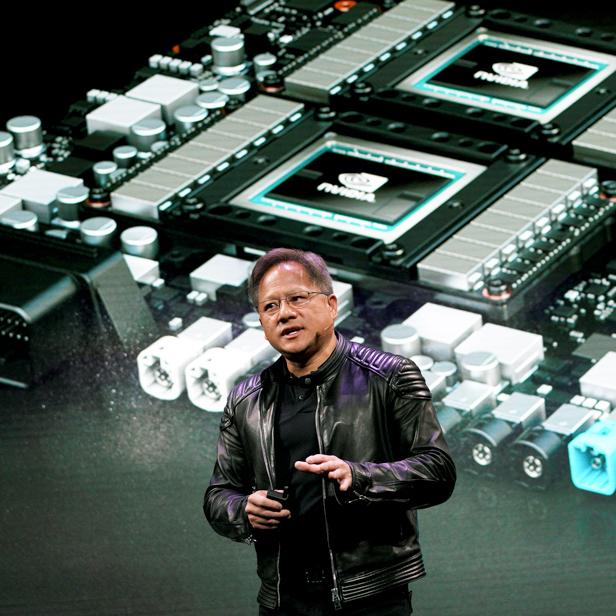

Until last month, most people outside techland would not have heard of Jensen Huang. Nor would most people have heard of Nvidia, the company he founded. Yet Nvidia is now one of the most valuable companies in the world. And Huang, if the hype is to be believed, is in the process of joining the software billionaires Bill Gates and Steve Jobs as a titan of the modern age.