If we’ve adjusted to the idea of an 80-year-old president who is super-psyched for another four years, then these veteran sleuths, all in late middle age, might seem positively dewy by comparison. Except they aren’t, possibly because their jobs age them even more drastically than life in the White House.

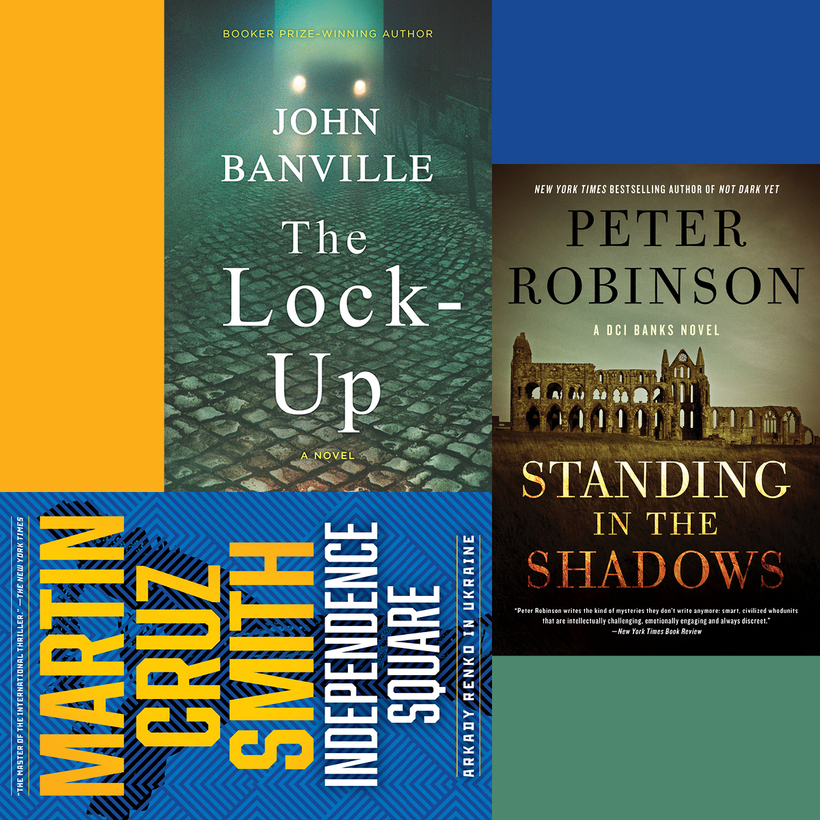

Three new novels find Arkady Renko, Quirke (just Quirke), and D.S. Alan Banks trying to ignore health problems and other insults to their well-being while still sharp and possessed of steady moral compasses. Now is the perfect time to get acquainted with these time-tested characters, if you haven’t already.

Renko’s creator, Martin Cruz Smith, has lived with Parkinson’s disease since 1993, and as it worsened, it became difficult for him to write as prolifically as he had before. But now Renko is back, with an affliction arguably worse than being the same honest policeman he was in Putin’s Russia that he was in Soviet times, when he made his debut, in Gorky Park—he has early-stage Parkinson’s. Cruz Smith’s unflinching description of its onset makes Renko’s decision to deal with his illness by not dealing with it seem both poignant and, given his job, foolhardy.

It’s the summer of 2021, and he needs to be in top form to execute the official Kabuki expected of him by his boss, Prosecutor Zurin, who only ever wants the appearance of an investigation, a special situation that’s led to plenty of free time for Renko.

Then, suddenly, everything happens at once. First, Renko is asked by a gangster friend to find his adult daughter, who has disappeared. She worked for a charismatic anti-Putin activist named Leonid Lebedev (a dead ringer for Alexei Navalny), who soon becomes an assassin’s target. Then, a hacker connected to Lebedev’s movement is shot to death in Gorky Park, and Renko has his hands full.

He has the misfortune of representing the police in the high-profile investigation into Lebedev’s death, which will have a predictable outcome. Still, he has to try. Scraps of evidence point to the Werewolves, a motorcycle gang with strong ties to Putin. Some of the book’s strangest set pieces are Renko’s conversations with the gang’s one-armed leader and his attendance at the Werewolves’ spectacular outdoor pageant in Crimea, an ultra-nationalist tribute to Mother Russia and the Soviet Union that would seem preposterous were it not borrowed from real life.

As Renko inches closer to identifying the actual assassin during a trip to Ukraine, he touches a nerve with the F.S.B., which has already found its scapegoat. Thanks to this and his newfound vulnerability, his continued existence has never been more precarious.

Cruz Smith’s signature humor of hopelessness remains intact, and his ability to build tension during a harrowing escape sequence will draw the sweat from any reader’s brow. Renko’s doctor gives him five good years before Parkinson’s disables him; maybe he’ll outlast Putin after all.

John Banville’s Dr. Quirke, a pathologist who has an informal working arrangement with the Dublin police, is also afflicted, but his ailment is mostly spiritual. He’s grieving for his wife, who got in the way of a hit man’s bullet in the last book, April in Spain, making him even more of a seething volcano than usual.

It takes little to set him off, and just about anything D.I. John Strafford, his unofficial colleague, does or says can send him over the edge. Both feel like outsiders in 1950s Dublin, where the power resides with the Catholic Church—Strafford because he’s an Anglo-Irish Protestant, and Quirke because of his boyhood in a Church-run orphanage.

Martin Cruz Smith’s signature humor of hopelessness remains intact in Independence Square.

Their uneasy partnership resumes when a Trinity College student is found dead from exhaust fumes in her car in a lock-up (meaning a rented garage, not jail). She is presumed by the police to be a suicide, but Quirke disagrees after examining her, and they reluctantly agree to look further into her death.

The victim was Jewish, yet she socialized with a moneyed, vaguely aristocratic German family. It seems too soon after the war for this kind of friendship, and Strafford senses something off about Herr Kessler’s artfully constructed country-squire persona and the source of his wealth.

Banville, who won the Booker Prize in 2005 for The Sea, retains his literary novelist’s embrace of ambiguity in his crime fiction and refuses to rein in his emotionally unruly characters. So while Quirke and Strafford’s methods may at times seem shambolic, Banville’s are not. The last chapter of The Lock-Up is as chilling and calculated as anything Patricia Highsmith could have devised.

For me, Peter Robinson’s superior plotting skills, strong social conscience, palpable sense of place, and, not least, voracious love of music put him in the pantheon of contemporary British crime writers. Which is why I was saddened to learn that Robinson’s latest book, Standing in the Shadows, would be his last. The English-Canadian writer died last October at 72.

The Lock-Up’s John Banville retains his literary novelist’s embrace of ambiguity in his crime fiction and refuses to rein in his emotionally unruly characters.

His enduring character, Yorkshire-based D.S. Alan Banks, is an exacting but compassionate boss, not without his flaws but a thoughtful man with a restless, wide-ranging intellect. Robinson made sure Banks evolved with the times, and he always wrote prickly, dynamic female characters.

If the British TV series featuring Banks hasn’t aroused your interest, you’re forgiven. The casting of the lead is mystifying, and the show doesn’t even try to capture the flavor of the books, but don’t let that keep you from reading Standing in the Shadows. Despite being the 28th book in the series, it’s actually a decent place to start.

The narrative toggles between the 2019 discovery of a skeleton in an architectural dig of Roman ruins in Yorkshire and the early 1980s diary of a university student whose ex-girlfriend is murdered. The young man is considered a suspect for a while, and by the time the police move on from him and the case grows cold, he’s been tainted by the publicity. Eventually he becomes an investigative reporter, never losing his curiosity about who the real killer might be.

Peter Robinson’s superior plotting skills, strong social conscience, palpable sense of place, and, not least, voracious love of music put him in the pantheon of contemporary British crime writers.

Meanwhile, Banks and his team deploy the latest in forensic technology to put a name to the bones, which definitely aren’t Roman, as the skeleton’s Tom Ford belt buckle proves. Robinson steers the two storylines into a perfect V, dropping a discreet hint or two about what the point of convergence might be.

The Alan Banks of 2019 seems content, savoring a glass or two of red wine and sampling the 2,000-LP collection a friend has left him in his will. It’s a lovely way to remember Banks and his creator, who leaves behind a legacy of novels that explore the thorniest regions of the heart, mind, and soul.

Lisa Henricksson reviews mystery books for AIR MAIL. She lives in New York City