Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma by Claire Dederer

About 10 years ago, a student asked to speak with me privately after class. He was a nervous young man, thinking I had all the answers. Finally, he asked, “Is Woody Allen a child molester?” He really thought I would know. I said, “We live in a nation of laws, and according to the law, he is not. There is, however, the court of public opinion.”

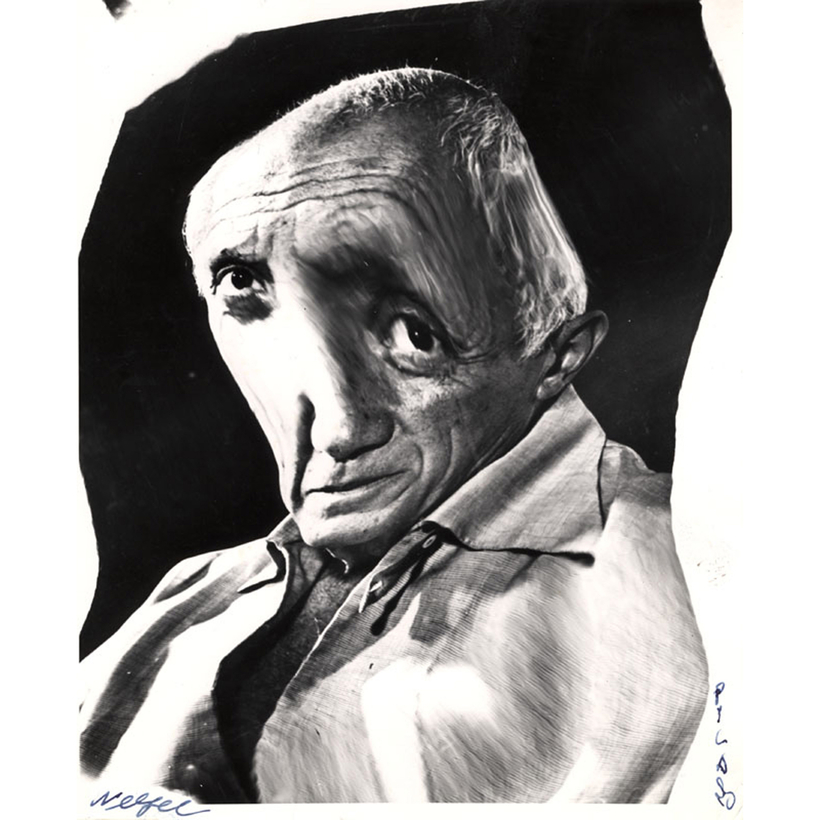

That was a long time ago; that conversation is now an artifact. The earth has been scorched by #MeToo and its aftermath. Art is not for art’s sake anymore. Must aesthetes now scurry into a speakeasy, check phones, and hide identities if they want to watch Chinatown, read Lolita, listen to Kind of Blue, or admire Les Demoiselles d’Avignon without the threat of Robespierre?